(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. But mama died one night. Papa decided sister Callie should go live with relatives. Tad tore up the burlap bear Mama had made for him.)

The next morning was Sunday, and all three of the Horn men—as Herman was considering himself quite a grown up little man by now—were out in the barn attending various chores. Since mama died they had not been able to make it to church. Papa always said he believed in God, but he didn’t believe in those holier-than-thou folks down at the church. At least that’s what he said to Tad in their evening discussions. Tad would reply by saying something silly like going to church was for sissies. That was when Herman would stop his eavesdropping and go to sleep.

As for Herman, he was very troubled. He wanted to believe there was a God, but he couldn’t believe in the same God the folks in the church down the road believed in. They believed in a God that hated anyone who wasn’t like them. Their God liked to hear hymns sung to him on Sunday but seemed to turn a deaf ear to pleas for help during the week.

“Horn! Horn!” their neighbor Mr. Cochran screamed as he drove up in his pickup. “Have you heard the news?”

Papa stopped what he was doing and stepped out of the barn door. Tad and Herman were right behind him. “What are you yelling about, Cochran?”

“It’s the Japs! They’ve bombed Hawaii! Someplace called Pearl Harbor!”

“I told you those Japs were going to pull something,” Tad said, spitting on the ground.

“Hush, Tad,” papa ordered, walking toward the pickup. “How bad is it?”

“Sunk several of our ships,” Cochran replied, more calm now, but very grim. “Lost a lot of our boys. The president’s on the radio right now. It’s war.”

The pit of Herman’s stomach turned hot and sour. He couldn’t believe anyone would stage a sneak attack like that. He hated to think that Tad, who never had a good word about anybody it seemed, was right about the Japanese. Most of all, it scared him about how this was going to change life again, which he thought had changed enough in the last few years.

“Herman, you finish up the chores,” papa said. “Tad and I are going into town with Cochran to get the latest on this thing.”

Once again Herman was left on the outside but he was used to it. He finished feeding the chickens and slopping the hogs. He moved the bales of hay around as much as he could, but he wasn’t as strong as papa whose job that usually was. He fixed lunch but ate by himself as papa and Tad didn’t return. Herman spent the afternoon talking to Burly about the Japanese and what would happen next. Finally he dozed off in the late afternoon and didn’t wake up until Tad and papa came through the door. Herman looked over the edge of the loft. Papa sat in his chair and Tad took his place across from him at the dining table.

“Son, are you sure you want to do this?”

Before he answered Tad looked up at the loft. “You might as well come down, Herman,” he said a little bit disdainfully. “This is going to concern you too. You might as well be in on it since you’re snooping around anyway.”

Herman felt embarrassed that Tad thought he was snooping but he didn’t say anything to deny it after he climbed down the ladder and stood rather shamefully between his father and brother.

“I’ve got to enlist, papa,” Tad announced. “First thing tomorrow morning.”

“I need you to help around the farm,” papa insisted.

“You got Herman.”

Papa looked at his younger son and then at Tad. “But I need a man.”

Herman tightened his lips and looked down. He tried to tell himself that papa didn’t mean that to hurt him. It was a fact that Tad was now more of a grown up than he was. But he still felt tears beginning to cloud his eyes.

“We can’t let those Japs get away with this,” Tad replied.

Papa sighed. “I guess there’s nothing I can say to make you change your mind.”

Tad didn’t even bother to answer but got up to walk to the kitchen. “Got anything for us to eat, Herman?”

Herman lurched toward the kitchen, bumping into the dining table. He was trying to talk without bursting into tears. “Um, I can warm up what I fixed for lunch.”

The meal went without talking, as most of their meals for the last few years had gone, but this silence was more frightening, more serious than any silence Herman had ever endured before. That night he didn’t even bother to talk to Burly but just let the pent-up tears flow. The attack on Pearl Harbor was all the children and the teachers were talking about the next day at school. The men teachers immediately left to join the army. Most of the boys said their older brothers were enlisting. In that, at least, Herman could speak with pride. His brother was the first in line that morning. In a few days papa and Herman took Tad down to the bus depot in their pickup and waited with him until It was time to go. Ages seem to pass between comments.

“Mr. Cochran said he would help around the farm as much as he could, to fill in what Herman can’t do,” Tad told papa.

“I can really do a lot,” Herman offered.

Papa ignored his younger son’s remark. “I don’t think he can spare that much time.” He paused. “But I appreciate the offer.”

Tad lightly touched Herman’s shoulder. “Be sure to write Callie that I’m going into the Army. And when I can get an address you can write me at, be sure to give it to Callie, okay?”

Herman frowned. “I didn’t think you liked Callie,” he blurted out without thinking. Immediately he winced because he knew Tad would light into him for being so stupid.

Instead, Tad looked off with a sad face. “I know it seemed that way to you lots of times, but I love her because she’s my sister.” He turned to Herman. “And Herman—“

“The bus is here,” papa announced.

Herman was glad Tad didn’t finish his sentence, because he knew he would have cried, and he didn’t want to do that in the bus station with all the young men going off to war watching them. Tad jumped up and grabbed his bag and lurched toward the bus. Papa and Herman followed close behind. Just as he was about to step up into the bus he turned and hugged papa.

“I love you,” he whispered.

Papa’s shoulders heaved with pain. “I love you too,” he choked out, then began crying.

Tad climbed aboard and sat by an open window. He leaned out and yelled, “I’m sorry, Herman, about—about everything.”

And then the engine started, and the bus was gone. Herman wondered if Tad was apologizing for tearing up Burly Senior, or for the way he had treated Herman all these years or for not actually saying he loved him. At this point, Herman decided, it didn’t make any difference. At least Tad said he was sorry. Herman was happy for that.

From then on there was even less talk at home. Papa kept his words down to instructions on the farm work and saying pass the salt. Slowly, sadly Herman came to care less whether they said anything at all to each other. One day in the spring Mr. Cochran helped with the planting. He hadn’t been needed much because Herman was trying extra hard to do his chores and Tad’s too.

“You’re a hard worker, Herman,” Mr. Cochran said. “We’ve been planting since dawn and you haven’t let up once.”

Herman smiled. “Thank you, sir.” He looked at his father to see if he noticed what Mr. Cochran had said.

“Yes sir, Horn,” Mr. Cochran continued. “We’re going to finish a lot sooner than I thought.”

Papa only grunted and continued planting.

“Have you heard anything from Tad?” the neighbor asked.

Papa stood erect and smiled. “You bet. He’s already made corporal. Always knew the boy was a born leader.”

“Does he know where he’s being dispatched?” he continued his questions.

“No sir, but if he had his choice he’d rather fight the Japs than the Krauts,” papa replied. “But wherever he goes, he’ll do his best. He always has.”

That night after Herman cleaned up the supper dishes he climbed into the loft without saying good night to his father. He had gotten tired of not hearing “good night” in return. Herman picked up Burly and looked him in his button eyes.

“Why does papa brag on Tad and not on me?”

Burly shrugged. Do you really want an answer? I think you already know why.”

Herman sighed. “I guess I do. Tad needs bragging on more right now than I do.”

“The bragging isn’t for Tad,” Burly corrected him. “It’s for your papa. He’s doing it to make himself feel better, and I’m afraid he’s going to need all the feeling better that he can get.”

Tag Archives: historical fiction

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Thirty-One

Previously in the novel: Novice mercenary Leon fails in a kidnapping because of David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the spy world is socialite Wallis Spencer, who dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol, has an affair with German Joachin Von Ribbentrop and marries Ernest. Each are on the Tanganyika Express to get their hands on the stolen Crown Jewels.Leon kills an agent to save Wallis.

Leon was a bit miffed. When he stabbed the German on the Tanganyika Express, the blood spurted all over his white linen suit. Leon took a detour through Cairo to buy a new one. He remembered Mrs. Ribbentrop years ago commenting on the high quality of Egyptian fabric. Even though he was quite pleased with the purchase, Leon mourned the passing of his first white linen suit.

Back home on Eleuthura, he ran down the dusty road to his hacienda. Jessamine bolted out of the gate and threw her arms around him. She did not comment on his new clothes which bothered him. If she truly loved him, he reasoned, she should have noticed and complimented him. Leon dismissed the thought as six-year-old Sidney raced to him and leapt into his arms.

“Papa! I’m so happy to see you! Let’s play!”

Leon swung him around and Sidney’s legs flew straight out. The boy giggled. Before Leon could toss the boy in the air, Jessamine grabbed her husband’s arm.

“Did everything go all right?” Her brow furrowed. “Pooka said something would go wrong.”

“Pooka always says something will go wrong.” Leon carried Sidney past her to their door.

She scurried behind him. “But something went wrong, didn’t it?”

“I didn’t get paid, if that’s what you mean.”

They entered through the garden to the front door. Leon looked down to see his mother Dorothy on her knees pruning the vegetables.

“Mama, get up.” He kept walking into the house.

“I like your new suit,” Dorothy called out as she struggled to her feet.

The next morning Leon arose early, put on an old ragged shirt and shorts and ate breakfast with Sidney, Jessamine and his mother Dorothy.

“You are a big boy now.” He tousled his son’s hair.

“Yes, I am.”

“When I was your age, my father took me out on his fishing boat. Do you think you would like to go out on a fishing boat?”

“Yes!”

“No, you will not!” Jessamine snapped.

“The boy needs to learn how to earn a living, dear.”

“We are wealthy,” she retorted. “He will not need to fish for a living.”

“Life is unfair.” Leon kept his eyes down as he bit into a scone. “Life is uncertain. What we have today can be gone tomorrow.”

Jessamine looked at Dorothy. “You can’t agree with Leon! Your own husband died on a fishing boat!”

The old woman put her fork down, pushed away her plate and turned to stare at her daughter-in-law.

“My husband was a good, honorable man. He lived for his family. He died for his family.”

“Well,” Jessamine huffed, “Sidney is too young. Leon was much older than six when he first went out on the boat.”

“No,” Dorothy was firm. “Jedidiah was a good man. He would have never let the child do anything that would hurt him, but a man must learn, build his body to provide for his family. Leon knows what he is doing. “

Jessamine pouted. “I shall have to talk to Pooka about his.”

Leon slammed his hand on the table. “You will tell Pooka nothing about our lives! That old witch knows too much about us as it is!” He stood, took Sidney’s hand and marched out the door.

Walking down the path to the Eleuthura dock, Leon waved to a fisherman on his boat. After he tossed the fellow a few coins, he lifted his son into the boat, jumped in and set sail.

“I like the water.” Sidney lifted his head and sniffed the breeze. “I think Mama’s trying to scare me.”

“But you’re not going to let her do that, are you?” Leon tugged on the line.

“No.”

“Do you want to help me cast the net to catch fish?” He smiled at his son.

“Yes!”

After hauling in a load of fish, Leon patted Sidney’s head. “Then you won’t mind working for the man who owns this boat, will you?”

Sidney’s eyes lit. “You mean, Jinglepockets?”

“His name is Nicholas.” Puzzled Leon asked, “Why do you call him Jinglepockets?”

“He’s always jingling coins in his pockets.”

Leon laughed. “That’s good. It’s always good to have coins to jingle in your pockets.” He paused. “Tomorrow you will start going out on Jinglepockets’ boat to learn to be a fisherman. The money you make, give to grandma. She’ll know what to do with it.”

“Does Mama know about this?”

Looking out to the horizon, he shrugged. “No, but don’t worry about it. I’ll tell her.”

“Oh, I’m not worried.”

“Good.”

They cast the net a couple more times and headed back to the dock.

“You know how grandpa died, don’t you?” Leon asked.

“A shark ate him.”

“Does that scare you?”

“Like you said, you do what you have to do to fill your family’s bellies. And everyone has to die. If you die for your family, all is good.”

Leon tossed the rope to Jinglepockets who tied the boat to the dock. The three of them unloaded the fish. Leon and Sidney began to walk away, but the boy stopped.

“What about the fish?”

“They belong to Jinglepockets.”

“Why?” Sidney wrinkled his brow. “We caught them.”

“But he owns the boat.”

“I saw you pay him, so the fish belong to us. Jinglepockets owes us money.”

“You’re a smart little boy, Sidney.” Leon put his arm around his son’s shoulders and guided him home. “Jinglepockets reminds me of Old Joe who taught me many things. He will be your Old Joe.”

The next day, as Leon and Sidney ate breakfast, Jessamine muttered her disapproval the entire time she tossed apples, cheese and bread into the tote bag for their lunch. They walked down to the dock. Leon lifted his son into the boat where Jinglepockets waited for them. When the fisherman cast off, Leon jumped into the boat with them. Sidney looked surprised.

“I thought I was working for Jinglepockets.”

“You are.” His father smiled. “I didn’t say I wasn’t coming along with you.”

They cast their nets as the sun rose in the sky. At noon, they paused to eat their lunch.

“Nicholas, do you know what the boys in town call you?” Leon asked.

“Jinglepockets,” he called out from across the boat. “Everyone calls me Jinglepockets but you.”

Leon leaned into his son. “Do the other boys pick on you?”

“No. One of the older ones wagged his finger in my face one time and called me a name. I grabbed his finger, bent it back and broke it. Nobody bothers me now.”

“Good for you.”

“You taught me that.” Sidney spoke around a chunk of cheese in his mouth. “Strike fast. Hurt them as much as you can.”

“Enough lunch!” Jinglepockets yelled. “Time to fish!”

When they docked that afternoon fish filled the boat. The three of them unloaded the fish from the boat onto the dock. Jinglepockets tossed a coin to Sidney. Leon took his hand and they walked down the road.

“Do you think you could kill a man?” Leon’s voice was soft and somber.

“You kill people, don’t you?”

“Not people. Just men.”

“Why not women? Don’t some women deserve to die?”

“Never.”

Sidney was quiet a moment. “I think I could kill a woman, if she was bad.”

“It doesn’t have anything to do with being good or bad. Sometimes people will pay you a lot of money to kill men. Or steal jewels. Or kidnap old men.”

“That’s how come we have a nice big house, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is.” Leon considered his thoughts. “Does it bother you?”

“No.” Sidney paused. “There’s a couple of boys I’d like to kill for free. Will you teach me the best places on the body to hit people to make them die fast?”

Leon glanced at the flower pot by the gate. Nothing was askew. “There will be time for that.”

“Papa.” Sidney stopped walking. “If I find something else I’d like to do to feed my family, it would be all right, wouldn’t it?”

“Of course, son. Family is most important.” Leon sighed. “I remember when I came home, you said, ‘Let’s play.’ I don’t think I’ve given you enough time to play.”

Sidney giggled. “Papa, anytime I spend with you is play.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Fifty-Five

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Stanton selects Duff, an AWOL convict,to impersonate Lincoln. Duff forms his own opinions about cabinet members, including Navy Secretary Gideon Welles.

Duff paused to look at the executive office second-story window and found Stanton gone. That meant the secretary of war was waiting. He feared what Stanton wanted to tell him. He climbed the service stairs, trying to compose his thoughts. When he entered the second-floor hallway and passed through the etched glass panel into the office, Duff heard Stanton instructing Hay.

“You may have your dinner hour now.”

“But I’ve a couple of questions about my notes,” Hay replied.

“I’ve a private appointment with the president which may last hours.”

“Would you like for me to stay to take notes?”

“I said I want you to leave the building. I’ve been quite clear.”

Duff detected a pause.

“Oh. Yes, sir.”

Entering the office with all the casualness as he could feign, Duff smiled at them. “Ah, Mr. Stanton, you remembered my order to stay for a couple of hours.” Taking pleasure from Stanton’s pinched Cupid’s bow lips, Duff winked at Hay and laughed. “I shouldn’t be too hard on the old man.”

Stanton’s cheeks burned bright red, and Duff flung one of his long, gangling arms around Hay’s shoulders. “I hope Secretary Stanton didn’t try to boss you into forgoing your dinner to take notes on our strategy session.”

“No, sir.”

“That’s good. I’ve noticed Mr. Stanton oversteps his authority by ordering around my personal staff.” Duff laughed again. “You know, he reminds me of the barnyard cock who strutted around the hens, thinking his crowing made the sun rise.”

As Hay chuckled, Duff pushed him out the door, firmly shutting it behind him.

“That,” Stanton said in an angry whisper, “was totally uncalled for.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” Duff replied. “I thought it sounded like something Mr. Lincoln would say.” He sat behind the large oaken desk, hoping to hide his shaking leg.

“Yes, and you know where his arrogance got him.”

“Mr. Stanton, a day doesn’t go by that I don’t think about Lincoln in the basement.” He looked grave. “What do you want?”

“You know very well.” Stanton walked to the desk, planting both fists on it. “What did Mr. Welles say to you?”

“That bewigged, doddering old fool? Merely gossip.”

“Gossip? What kind of gossip?”

“The campaign in Vicksburg will end successfully, possibly today.”

“And?”

“He wants Grant to replace Meade.”

“Why replace the victor of Gettysburg?”

“Circumstances change quickly. Our record of changing generals suggests that trend will continue.”

“You see-it’s futile to keep a secret from me.” Stanton cocked his head to eye Duff. “You’ve another secret.”

“Nothing serious.” Duff stalled Stanton, thinking of some crumb to toss him, something to appease him, something somewhat related to the war—but not connected to Alethia.

“It’s foolish to defy me. Spit it out.”

“It’s something Mr. Hay said. Don’t blame him. He thought he was reporting it to the proper authority.”

“What?”

“He came to my bedroom several months ago…”

“You waited to tell me?”

“I had my reasons. One being concern for your personal life.”

Stanton took a step back.

“As I was saying, he visits me often late at night to share stories he’s heard at some party. I didn’t know social gossip interested you. Besides, it involves someone you know.”

“Who?”

“Jean H. Davenport Lander.”

“Don’t believe gossip.” He shuffled his feet. “I was between marriages when Jean and I—enjoyed each other’s company. This was before she married Colonel Lander.”

Duff gained confidence; for once, he held the upper hand. Smiling at Stanton, Duff was certain he saw beads of perspiration across his brow.

“Mr. Hay, it seems, talked to her at this party.”

“Go on.”

“She seemed concerned, he said, about a young Virginian she had met who boasted of a great, daredevil thing.”

“A daredevil thing?”

“What if he were planning an assassination?”

“That’s highly unlikely.”

“I thought, how ironic if I were killed instead of Mr. Lincoln.”

“Did she mention his name?”

“I don’t know.”

“If Mr. Hay mentions it again, tell me.”

Before Duff responded, office messenger Tom Cross rapped softly at the door and opened it. He timidly stepped in, his eyes wide with apprehension.

“Yes, Tom. What is it?” Duff asked.

“We just received a message from the Soldiers’ Home.” He paused to swallow hard. “They want you to come immediately. Mrs. Lincoln’s condition, it’s worse. She’s got a fever and is in and out of consciousness.”

Burly Chapter Eighteen

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. But mama died one night. Papa decided sister Callie should go live with relatives. Tad tore up the burlap bear Mama had made for him.)

In the ensuing, hard depression years, Herman and Tad never talked about what happened to Burly Senior. And, curiously enough, neither did Herman and Burly. From time to time one or the other would wonder what Callie and Pearly Bear were doing, but they never mentioned Papa Bear.

Herman found he liked school very much; in fact, he was very good, always making the best grades in his class. He was very proud of this and bragged to Burly all the time, but he never mentioned it around Tad, for his grades, while not bad, were not the best. Papa never commented on any of his sons’ grades, just writing his name on the cards and sending them back to the school.

“Sometimes I wish papa would brag about me some,” Herman said with a sigh one day after he had taken his report card home. “It would make me feel good.”

“But that isn’t your father’s way, is it?” Burly asked. “So why wish for something that your head tells you will never happen?”

“I suppose you’re right,” Herman replied. “It’s just that the grades make me feel so good. I know I’d feel even better if papa was proud of them.”

Burly was strangely quiet. Finally Herman noticed the silence and looked down at Burly. “Is anything wrong?”

“I think you’re putting too much importance on that report card.”

“What do you mean? Isn’t doing well in school important?”

“Of course,” Burly said. “But have you noticed you only seem to like yourself a lot after you get your report card?”

Herman frowned. “I like myself all the time.”

“I don’t think so.”

“Well, maybe I like myself better after report card time,” Herman admitted. “After all, there it is, in black and white. Herman Horn is smart and he behaves well in school.”

“But one of these days you won’t have it in writing every six weeks how good you are,” Burly debated. “And it will be up to you to like yourself without any help.”

Herman thought a moment and then laughed. “Burly, you’re funny.” Then he forgot about the whole thing.

But Burly didn’t forget it. He knew that Herman was in for some hard time, and he didn’t know how to help him see it. Burly didn’t know how he knew it; after all, he was only a stuffed burlap bear, but he knew it as surely as he knew his papa had disappeared and he might never see his mama again.

Christmases didn’t come to Herman’s house anymore after Callie left for Houston. He didn’t bother to make a card for papa and he didn’t even mention the holidays to Tad. He did talk about it to Burly late at night, and on Christmas Eve he and Burly sang carols softly to themselves. Herman laid back and imagined how Christmas would be one day when he was the papa and he had children of his own.

“No matter what happens,” he whispered to Burly, “I’ll always make Christmas special for my children.”

“I know you will,” Burly replied, cuddling close to him, fantasizing how nice Christmas would be with Herman and his new family, naturally fantasizing that he would be a part of it.

Another numbing year passed, and Christmas was coming upon Herman and Burly again. The now twelve-year-old boy had come upon some red material on the side of the road and was figuring out how to make a hat or coat out of it for Burly. Maybe a muffler, he thought. He was playing with the piece of cloth one Saturday night in the loft as papa and Tad sat downstairs looking at the newspaper. In the last couple of years they had grown closer together as Herman and Burly had grown closer. Herman looked over the edge of the loft at them discussing the world and felt no twinges of jealousy or sadness. He just accepted the fact that papa had found comfort in his nineteen-year-old son.

“The Japs are in Washington talking to the government,” Tad said.

Papa grunted.

“I don’t trust them,” Tad added.

Papa grunted.

“I’d like to kill all of them.”

Herman put the cloth aside, deciding it would best make a muffler and plopped into his bed, gazing out of the window at the cold black sky and the twinkling stars.

“You always eavesdrop on their conversation until one of them says something bad about someone or something else you don’t like,” Burly observed.

“Is that what I’m doing?” Herman frowned. “Eavesdropping? I just thought I was watching my family.”

“Think real hard about it.”

“I guess I am,” Herman confessed with a sigh. “But what’s so bad about that?”

“Nothing, as long as you know that’s what you’re doing.”

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Thirty

Previously in the novel: Novice mercenary Leon fails in a kidnapping because of David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer, who dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol, has an affair with German Joachin Von Ribbentrop and marries Ernest. Each are on the Tanganyika Express to get their hands on the stolen Crown Jewels.

Ernest Simpson was such a nice, decent and easy-going husband, Wallis thought as she boarded the Tanganyika Express in the heart of Africa amidst dreadful plains which seemed to go on forever. The sky was dark, like it was going to storm again soon. Her mind went back to her husband. It was a shame that she did not love him. He was reasonably good looking, an excellent dance, an understanding, giving lover, and not at all clinging or overly inquisitive. But when MI6 contacted her for a mission, she was required to go. For instance, when she was notified of her latest assignment she was in a fitting at her favorite London designer. A note was slipped into the bodice of her new gown.

“Noon. White Chapel. Queen Betty’s Fish and Chips.”

Wallis thought it humorous to rendezvous in the district known for its ladies of the night and Jack the Ripper. A waiter seated her in a booth in the back by the kitchen. Within a few minutes an old man sat opposite her.

“The crown jewels have been stolen.” He had a thick Cockney accent.

“Don’t look at me.” Wallis puffed on her cigarette. “If I want jewels I just sleep with a man and then he gives them to me.”

“We know who stole them.” The old man pushed an envelope across the table toward her. “Be on the Tanganyika Express. Walk by the designated compartment at midnight. A door will open. A hand will appear and will drop a velvet pouch in your purse. Immediately return here and give the pouch to me.” He tapped the envelope. “The tickets, everything you need to know, are in here.”

“I don’t get to kill anyone this time?”

“If you’re lucky. Maybe. Take your knife.”

That evening in their Bryanston Court apartment over a small supper comprised of soup, mashers and bangers, Wallis announced to Ernest she was leaving in the morning for Africa.

“One of my girlfriends told me of a witch doctor living in the wilds who claimed a cure for heart disease. I must dash off, obtain the herbal potion and rush to America to administer it to mother. After all, when we visited her recently she looked dreadful.”

“Didn’t she also inform you your brown dress looked dreadful?”

Her hard slit of a mouth turned up in a passing imitation of a smile. “Ernest, darling, you are way too sensitive. You must learn to live and let live. Forgive and forget.”

Ernest stood, picked up his dishes and those in front of Wallis to carry them to the kitchen. “I’ll write you a check before you leave tomorrow. You must always travel in comfort, even if you are on a mission of mercy.”

MI6 had issued all the funds she needed for the assignment, so she used the money Ernest gave her to drop in at Paris on her way. She had decided to take the route to Cairo, down the Nile and make the connecting trains to the Tanganyika Express. The Express had the reputation had a reputation of serving only the elite of European society. She wanted to fit in. In Paris shops she bought a black velvet hat with a brim so wide it dropped in front, covering both her eyes and nose. It revealed only her crimson lips. The crown concealed a giant pin to serve as a back-up weapon if she couldn’t get to her knife fast enough.

Her leopard skin coat had giant deep pockets in which to hide the crown jewels. A thought wafted through her brain that if the authorities did not have an exact count of missing diamonds she could sneak one away to squirrel into one of the dark crevices of her leopard coat pockets. They probably did count them, Wallis decided. Damned insufferable English efficiency. It was for the best anyway. They took only the small jewels and who wanted a small diamond even if it were part of the royal jewel collection?

The Nile proved tedious to Wallis. Just a bunch of dirt and mud buildings. Even the ones shaped like pyramids. All the good stuff had been taken out of them. She did catch up on her sleep. Wallis led a very active life and every now and then her body would beg for an extended sleep, which on this trip she has able to provide. When she reached the headwaters of the Nile she connected to a train which took her to the station where she could board the exotic Tanganyika Express.

Wallis’ dining experience on the Tanganyika Express was boring. No man offered to sit with her. Probably was the huge hat. Just as well. MI6 gave her strict orders not to be identified. The worst part of the evening was observing Mrs. Barnes, wife of the British ambassador. The middle-aged woman had not one socially redeeming quality—she was dumpy, her unattractive clothes did not hang well on her body, she wore too much makeup and her table manners were atrocious. She was a nymphomaniac which made her a prize above measure for men. At least three sat at Mrs. Barnes’ table during the meal. The first was a tall German gentleman with blond hair and impeccable manners. Wallis turned her head to eavesdrop on the conversation. She could not understand a word he said but she nearly swooned at the guttural tones emitting from his throat. A well-dressed young black man passed the table a couple of times. He wore a lovely white linen suit. Wallis could tell he was interested in talking to Mrs. Barnes but as long as the German sat there wooing her, he continued his exploration. Wallis felt it was an intelligent decision since interrupting the German could Start World War II in an inconvenient space.

After he seemed to give up the cause, the well-dressed black man left the dining car. Wallis could not help but follow his departure. Her attention quickly was drawn back to the Barnes table where she had shrieked something unintelligible, stood by table facing a sandy haired gentleman who had a slender frame. She decided the man had a certain élan which made him more fascinating than the German. Wallis was right. Within a few moments the German stalked away, allowing the remaining gentleman to sit, lean forward and begin whispering sweet nothings to the ambassador’s wife. Suddenly the thought struck her that Mrs. Barnes was the one with the diamonds. Who would be dumb enough to trust her with the stolen jewels? They parted and exited at opposite ends of the dining car. Wallis never saw the man’s face. All she could determine was that he carried himself as though he knew he was better than anyone around him and he was comfortable with that fact.

One of those three men would open Mrs. Barnes’ compartment door at midnight and drop a pouch of diamonds into her purse. Which one she did not know, nor cared. She looked at her watch. An hour before midnight. Wallis had time for a nightcap in the lounge car. When she entered she saw Ambassador Barnes in a corner with a group of men. Wallis sat close to them so she could hear their conversation.”

“This is my last one.” A man announced. “I am passed my bedtime.

“Oh God no,” Barnes slurred. “Please stay and be my excuse for returning late to my wife.”

“And why is that?” another man asked. “I thought your wife to be—“he paused awkwardly to come up with the right word “—sweet.”

“My God,” Barnes muttered, “that’s the bloody worst thing you could say about a woman. Heaven’s sake, she is. Sweet, that is. I want to wait until after midnight. Hopefully she will be asleep by then.”

That’s good. That way he won’t be in the middle of some messy political intrigue. She took her time sipping on two martinis until the clock neared midnight. As the hands of the clock were straight up, the Tanganyika rains returned. Sauntering out and into the sleeping car, she saw a compartment door open and a man’s arm, sans shirt, extended out with a small velvet pouch. As she walked by, she opened one of the wide pockets of her leopard skin coat and the pouch dropped in. She kept walking at an even pace and exited the sleeping car and, trying not to be pelted by rain, was about to enter the next when the door opened behind her and Wallis felt a power arm around her neck. Wind caught her broad brimmed black velvet hat and carried it out to the dark African countryside. The German looked around into her face and smiled.

“Herr Von Ribbentrop will be surprised to learn you were involved in this.”

Before he could say or do anything else, Wallis yanked her knife from her purse. The German went limp which gave Wallis a chance to twist around and cram the knife up under his ribcage. As the German fell, a crash of thunder accompanied a flash of lightning which revealed another knife was stuck in his temple. She quickly stepped aside and allowed the body to fall from the train and into the darkness. Wallis was surprised to see the black man in the nice white linen suit step forward. His right jacket sleeve was splattered by the German’s blood.

“I don’t believe in killing women,” he said in a Bahamian accent.

“I can take care of myself.” Wallis tried to figure out how to extract herself from the predicament without losing the diamonds.

“Don‘t worry. You can keep the jewels. I didn’t need the money from this job anyway.”

Wallis smiled and pursed her thin lips. “In that case, thank you.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Fifty-Four

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Stanton selects Duff, an AWOL convict,to impersonate Lincoln. Duff forms his own opinions about cabinet members.

As the Cabinet members left, Welles turned to Duff.

“Mr. President, would you walk with me to the gate?”

“No,” Stanton interjected. “He’s much too preoccupied.”

“I’m not preoccupied at all.”

“Good,” Welles replied, taking Duff by the crook of his arm and leading him down the hall. “How’s Mrs. Lincoln after her carriage accident?”

“Very well,” Duff said, ignoring the exasperated grunts from Stanton behind them. “Doctors at the Soldiers’ Home said her head injuries were minor. It’ll be good for her to recuperate in the cool Maryland foothills.”

“Yes, it can be quite sweltering in Washington during the summer months.”

They began down the grand staircase.

“You know, Mrs. Welles always inquires about Mrs. Lincoln. She’s quite fond of her. Often she has protested the unfair attacks on her in the newspapers.”

When they reached the foyer, Welles gave a wary glance up the stairs and then at the front door guard, John Parker, who was already red in the face from drinking.

“Good morning, Mr. Parker,” Duff said. “I’m escorting Mr. Welles to the gate. I won’t be long.”

“Very well, sir.” Parker’s voice was thick with whiskey.

As they walked down the steps, Welles leaned into Duff.

“I wanted a private word with you, Mr. President,” Welles said in a hushed voice. “It seems Mr. Stanton has been omnipresent the last few months.”

“Really? I hadn’t noticed.” Duff raised an ingenuous eyebrow.

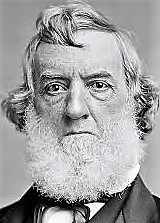

“Mr. President, I wish I had your gentle wit.” Welles chuckled and shook his bewigged head.

They took a sharp turn to stroll through the garden to the turnstile gate.

“What’s on your mind, Mr. Secretary?”

“I was less than forthcoming during the Cabinet meeting,” he whispered. He stopped to examine a rose bush. “I wish I still had my sense of smell. Roses have a marvelous bouquet.” Again Welles looked up, this time at the second-story window, where Stanton stood glaring at them.

“I assume you weren’t forthcoming because of Mr. Stanton.”

“I don’t trust him.” Welles straightened and looked at Duff. “He exudes the aura of frustrated ambition. Put quite bluntly, Mr. President, he covets your job.”

“So do Mr. Chase and Mr. Seward.”

“But not as much as Mr. Stanton.”

“So what do you want to tell me?”

“I’ve my sources at Gettysburg,” he whispered as he gripped the top of the turnstile gate. “On both sides. I don’t want Mr. Stanton to know.”

“What is it?”

“On the Confederate side, my sources say General Lee isn’t well.”

“I’m sorry to hear that.”

“It’s his heart,” Welles said, leaning into Duff. “His appearance indicated a heart attack. If that’s so, his judgment’s impaired. He’ll make mistakes. His decision to attack Little Round Top was disastrous. There’s no question his decision to charge the center of the Union line today will be an unequivocal failure.”

“So that’s good for us, correct?”

“Not necessarily. My sources on our side tell me General Meade errs on the side of caution to the extent he won’t pursue Lee when he retreats.”

“That wouldn’t be good.”

“Your understatement is amusing,” Welles said wryly. “You—we—will need a replacement for General Meade.”

“Of course.”

“Before Mr. Stanton makes his suggestion, I’d like to recommend General Grant.”

“But he’s mired in the Mississippi mud outside Vicksburg,” Duff said. “And my sources tell me he’s disappeared in the bottle.”

“My sources,” Welles said, shaking his head, “which I assure you are faster and more accurate, say Mrs. Grant arrived in camp, and the drinking stopped.” His mouth went close to Duff’s ear. “They also say he’s close to a great victory. Vicksburg’s capitulation may come as soon as tomorrow.”

“Thank you for your information,” Duff said, glancing over his shoulder to the second-story window, where Stanton still glared down upon them. “I’ll consider your recommendation of General Grant most seriously—as I’ll consider nominations from other Cabinet members.”

“Don’t let Stanton sway you.” Welles grabbed Duff’s arm. “He’s one of that breed who believes it’s impossible that he could be wrong, therefore any action he takes is justified.”

“We all, at one time or another, have to fight such delusions,” Duff said with a slight smile.

“If, sir, you’re implying I’m suffering from that delusion,” Welles said, pulling away from Duff, “you’re wrong.”

Deciding to allow prudence to prevail, Duff nodded and extended his hand. A moment passed before Welles took it. He turned abruptly, went through the turnstile, and walked down the path to the War Department.

Burly Chapter Seventeen

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. But mama died one night. Papa decided sister Callie should go live with relatives.)

Late one afternoon in the loft Herman was having a nice long talk with the two bears when he heard the front door open. “Uh oh. Tad’s brought Leonard and Stevie home with him again.”

“Don’t get upset before they even say anything,” Burly Senior told him.

“Who knows?” Burly added. “They might even be nice to you today.”

By that time the three teen-aged boys were climbing the ladder, giggling poking at each other. They stopped short when they saw Herman.

“You here?” Stevie growled.

Leonard walked over and poked Herman in the shoulder. “Don’t you know? He’s always here because he’s too weird for the other kids to play with.”

Stevie glared at Herman, his hands stuck in his pockets. “Doesn’t he have chores?”

“I did my chores,” Herman replied, looking out the window.

“Then go find papa and ask him to give you something to do,” Tad ordered. “Get out of here. We want to talk.”

Leonard picked up Burly’s red wooden car and examined it. “What’s this?”

Tad glanced at Herman. “Just one of the kid’s toys.”

Laughing, Leonard ran its wheels on the floor. “Hey look! A smash up!” Then he ran the car into the side of the wall, causing it to splinter into small pieces.

Herman twitched but said nothing.

“Leonard, you’re such a jerk,” Tad spat.

His friend shrugged. “Big deal.”

Herman jumped off the bed and headed toward the ladder with Burly under his arm.

“Boy, you don’t go nowhere without that bear stuck under your arm, do you?” Leonard sneered.

“How old is he?” Stevie asked Tad.

Tad shifted uneasily on his bed. “Heck, I don’t know.”

Leonard leaned down into Herman’s face and smiled a stupid grin. “Just how old is the eety-bitty boy?”

Herman felt his neck turn red hot. “Eleven.”

“Don’t you think that’s a little old for you to be carrying around a doll?” Stevie asked.

“Burly’s not a doll,” Herman corrected him. “He’s a bear.”

“Ooh, that’s a big difference,” Leonard said with a snort. “No wonder no decent kid will play with you. You’re still a baby with his dollie.”

“Stop it, Leonard,” Tad ordered.

Leonard looked around at Tad who was glaring at him. After a while Leonard walked over to the bed and picked up Burly Senior. “You might as will take your other dollie, too.”

Without thinking, Herman blurted out, “Oh no, that’s Tad’s.”

As soon as the words were out of his mouth Herman knew he had made a mistake. He looked quickly at Tad who turned a bright shade of red.

Leonard smiled and his eyes twinkled, as though he had found fresh meat to bleed. “You mean little Taddie Waddie sleeps with a dollie?”

Stevie grinned but didn’t say anything, only snorted. Before anyone could say more Herman scurried down the ladder and out the front door. Herman ran to the barn and hid in the farthest, most dimly lit corner. “Oh, why was I so stupid?” he berated himself.

“You weren’t being stupid,” Burly corrected. “You were being honest. That’s what you are.”

“But I shouldn’t have said that in front of Tad’s friends,” Herman continued. “Did you see how red he was? Those boys are really going to make fun of him. And then he’s going to let me have it.”

“Yes, Tad did look embarrassed,” Burly agreed. “And his friends will probably tease him. And there’s a good chance he will fuss at you. But you know what? After it’s all over, you’ll still be Herman and Tad will be Tad. You’ll go on letting the truth tumble out of your mouth. And Tad will get mad too easily. But you will keep on living.”

Herman looked down at the dirt. “I guess so.”

In a few minutes Herman heard the three boys leave the house and run down the road. Then he remembered it was his turn to cook supper that night. Herman scurried into the house, put Burly up in the loft and rushed around the kitchen getting the food ready. At supper Herman watched Tad out of the corner of his eye. He half-way expected Tad to get even by complaining about the food, but he didn’t.

“Good vittles, son,” papa mumbled.

“Yeah, not bad,” Tad added.

Again Herman tried to tell by Tad’s voice if he were angry. He didn’t sound angry, but his voice didn’t sound normal either. Herman couldn’t figure it out. After they ate, Tad helped wash and dry the dishes. He was strangely polite but seemed to be somewhere else, somewhere very sad. “Thank you for helping with the dishes,” Herman said.

Tad walked away without looking at him. “Think nothing of it, kid.”

That night, when all was quiet, Herman roused Burly. “I don’t understand what’s the matter with Tad. I thought he was going to be mad at me.”

Burly stifled a yawn. “That surprised me too. Maybe papa can help us figure it out. I think he knows more about Tad than either of us.” He waited a moment, then whispered, “Papa?”

There was no reply.

“Papa?” Burly repeated.

Only silence answered him.

“That’s strange,” Burly said. “Papa always joins in on talks.”

“Let me see if he’s over there.” Herman tiptoed over to Tad’s bed. As well as he could see in the dark, Herman couldn’t find Burly Senior. Usually he was tight within Tad’s arms close to his chest, but not tonight. Herman got returned to Burly. “He’s not there.”

“That’s odd.”

The two of them decided to look for him the next day after helping papa in the fields. In the morning Herman left Burly in the loft as he always did and went to the cotton field with papa and Tad. The hours went by slowly as he hoed the weeds away. Later that afternoon papa walked by.

“That’s all for today,” he said and kept on walking.

Herman scampered back to the house and got Burly. First they looked under Tad’s bed, thinking Burly Senior might have slipped under there. Then they looked in the big old trunk at the end of the room where mama and papa kept special things, like stacks of old letters tied with pink string, the dress mama was married in and yellowed photographs of stern, erect people Herman didn’t know. Burly Senior wasn’t there either. “There’s only one thing left to do,” Herman said with a sigh. “That’s to ask Tad.”

“You’re very brave to do that,” Burly replied. “Will you ask him after supper tonight?”

“No,” Herman answered as he carried Burly down the ladder. “I’m going to ask him now.”

They went down the dirt road toward the field but stopped abruptly when Burly gasped, “Oh no!”

Down on the ground, in a trench was a mass of torn burlap. Down feathers, wadded up for stuffing was strewn everywhere. And a burlap ball, with buttons sewn on it, was smashed flat.

“Papa,” Burly whispered.

Herman kneeled down by the remains of Burly Senior. He picked up the different pieces, a torn patch that was his chest, little puffs that were his arms and legs, and the flattened ball that was his head. He whispered to them, cried over them, but they were just pieces of burlap now. The life was out of them, stomped out.

“Did Tad do this to my papa?” Burly asked.

“Yes. Or he stood by and watched Leonard and Stevie do it,” Herman said, trying to hold back the tears. He looked down the road at the field. “I’m going to let him have it for this.”

“No,” Burly ordered. “You can’t say anything.”

“Why not?”

“Because papa belonged to Tad,” Burly explained with difficulty. “Even though he was my papa and he was your friend, he belonged to Tad. And Tad could do anything he wanted with him.”

Herman glared down the road a moment and sighed. “I suppose you’re right.” Then they walked home without a sound. No words were spoken during supper either. Herman could tell Tad was avoiding looking at him. Now he knew why Tad was strangely polite and quietly sad. Tad knew what he had done, and he couldn’t face Herman. That night Herman couldn’t sleep. He kept seeing Burly Senior smashed on the side of the road, never to speak to him again or give him wonderful advice.

“Oh Burly,” Herman asked. “Why did Tad do it?”

“Tad’s growing up. Maybe he thought papa was holding him back in childhood. Maybe he decided grown up boys don’t hug a bear at night.”

“That’s stupid,” Herman said, spitting the words out.

“No,” Burly corrected him. “That’s human.” He paused and snuggled close to Herman. “When it comes time for you to grow up, you won’t do that to me, will you?”

Herman sat up. “No sir, Burly. You’ll always be with me. If doing without you means growing up, then I won’t grow up!”

“Oh no, you’ve got to grow up,” Burly said. “I want you to grow up. It’s just that I’m scared about what’s going to happen to me.”

Herman hugged Burly tightly. “Don’t worry. You’ll always be with me.”

But Burly wondered, as Herman fell into a deep sleep, if his friend would be able to keep his promise.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty-Nine

Previously in the novel: Novice mercenary Leon fails in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury because of David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer. Wallis, in quick succession, dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol, has an affair with German Joachin Von Ribbentrop and marries Ernest.

Hitler wants Ribbentrop to steal the Crown Jewels.

David thought traveling was such a bore with his valet Tommy Lascelles hanging around like a snoopy younger brother—witnessing his social indiscretions and eagerly reporting back to Papa and Mama. Tommy believed in the old order of royalty, honorable without any hint of moral turpitude. He rarely smiled, obsessed with duty, stiff, and emotionless. Like a marble statue Tommy was unable to feel love, joy, anger or pain. An eternal life of nothing. It’s not like Tommy Lascelles had not experienced sexual pleasure—he had a wife and children. At some point, Tommy let down his proper British face to bask in wanton fleshly delights with his wife, both legally and morally his own.

Well, David told himself, Tommy’s private life was strictly his own and not open to criticism, even by the Prince of Wales. He had more a more pressing agenda—retrieving gems stolen from the Crown Jewels of England. David stopped before entering the dining car of the Tanganyika Express hurtling its way through the night to Dar Es Salaam during one November’s frequent short rainfalls. He regarded his reflection in the dark window pane. Every hair was in place. His tanned face was without flaw. He smiled. His teeth gleamed. Adjusting his shoulders, David made certain the center button in his hand-crafted dinner jacket was fastened. Last he made sure all the trouser buttons at his crotch were secure. His father often forgot to button after visiting the loo, creating an awkward situation at the palace.

He looked through the window into the dining car to spot the ambassador’s wife, Mrs. Edith Barnes—the lady who possessed a stash of gems from the crown jewels. The man who actually stole them from the Tower of London—her brother-in-law and assistant tower administrator—had been immediately apprehended. The thief wasted no time confessing Mrs. Barnes had seduced him into stealing the jewels. Now no one in the justice community cared about punishing wife of a British ambassador. All the British government wanted was the jewels back. They knew that Ambassador Barnes and his wife Edith took an ocean liner from Portsmouth to Leopoldville, rode a steamer up the Congo and then transferred on several trains to reach the capital of Tanganyika territory. The ambassador used most of his travel time in conference with African officials trying to iron out lingering details of land concessions made by Germany at the end of the Great War.

David noticed a gentleman had taken the seat opposite to Mrs. Barnes at her dining table. He sat with his back to David who felt comfortable making certain assumptions about the man. He was tall, and, from the way his jacket hung on his frame, he was athletic. His blond hair was closely cropped. And though he could not see the man’s face, David was sure he was handsome because of the glint in Mrs. Barnes’ eyes.

The prince made an unobtrusive entrance and slid into a chair at a table across the aisle from Mrs. Barnes. He had met her at several cocktail parties in the Mayfair district. Whether he had bedded her, he could not remember—probably did. She had not become close enough to be given the honor of using his family name of David instead of the royal Edward. Once her gaze drifted from the stranger’s eyes she would see him and immediately abandon her latest glittery toy. David slumped slightly in his chair, lit a cigarette and puffed away like he didn’t care. The man must have been more intriguing than David thought because he didn’t hear her shriek of recognition. Soon his attention was drawn to the fact a waiter had not appeared to offer him a glass of wine. He leaned a couple of inches toward Mrs. Barnes so he could hear the conversation. Her companion was speaking.

“My dear, never have I seen such beauty in one woman.”

He had a German accent but otherwise spoke clear and distinct English.

“Forgive me for my bluntness for I am a blunt man.” The German’s voice was deep and throaty.

David thought Mrs. Barnes was going to orgasm right there between the salad course and the entrée. There was no doubt this was the agent sent to retrieve the Crown Jewels from the ambassador’s wife. Was Hitler behind the plot? He shook his head. His imagination was running away with his good sense. But who else would want to steal the Crown Jewels? Who would be crazy enough to try? He tapped his long slender fingers on the table, trying to decide whether to hope if Mrs. Barnes would notice him on her own or should he introduce himself, before the German swept her off her feet and into her compartment.

Just as the stranger extended his large hand to touch hers, she glanced away and saw David. She sprang to her feet and gasped loud enough to be heard all the way in Rhodesia. “Oh my God! The Prince of Wales!” She attempted an elaborate curtsy which resulted in her right hand slapping the German’s face. “I had no idea your Highness was in Africa!”

The German melted into the background and eventually out the door. David could not help but notice however that he lingered outside, peering through the window.

With a weak smile, David said, “Have we met?”

“My dear Edward, we met at Upson Downs last season.”

“Oh yes. You were in the large blue hat.”

She giggled and gave him a playful slap on his shoulder with the back of her hand. “You naughty boy. You know we all were in blue for the races.”

“Hmm, your husband is in the diplomatic corps.” He crinkled his nose as in thought. “Barnes….that’s it. Mrs. Edith Barnes.”

“I would ask you to join me but I have a rather intense headache at the moment,” she whispered.

“My goodness.” An evil grin flitted across his thin lips. “You must remember how I can make headaches go away.” David glanced at the window in the door. The German was still there. “Perhaps your husband could join us.”

“Oh! He’s in conference two cars down. He’ll be involved with Tanganyikan officials until dawn.” She cocked her head. “I thought perhaps you were on the train to advise them in their deliberations.”

“No.” He puffed on his cigarette. “I’m on safari…hunting big game.”

“Fascinating. You must tell me all about it.”

“But I thought you had a headache.”

Her hand stroked his tanned cheek. “You’ve already made that go away.”

“In that case, please sit down and join me in a bottle of champagne.”

Mrs. Barnes sat and eventually succeeded in making David remember how they had made mad passionate love in a luxury hotel suite in the West End of London.

“Didn’t we see a play first?” David asked.

“Of course. It was written by Jerome Kern.”

He looked at the door and saw the German gone. He smiled, took her hand and kissed her fingers. “I think it’s time for an encore.”

She whispered her compartment number into his ear. “Meet me in fifteen minutes.”

When David glimpsed the door, this time he saw Tommy glaring at him. They returned to the prince’s compartment. After they entered and David latched the door, he sighed. “What’s happening now?”

“We’ve received a wire about your father.” Tommy was grim. “It’s not good.”

“Is he dead?” David tried not to sound too hopeful.

“No. But very close. He had another stoke. We must leave immediately for London.”

“Do you know the last thing he said to me?”

“No, sir. I do not.”

“He said, ‘You dress like a cad. You act like a cad. You are a cad. Go away.’”

Tommy looked down at a notepad. “A car will be waiting for us at the next stop. From there we will motor to the nearest airport where we will plane to Casablanca and embark on a naval ship to Portsmouth. You have less than thirty minutes to pack.”

“In thirty minutes I plan on bedding the wife of our ambassador.”

“Your father was right. You are a cad.”

David turned and, without a word, left the compartment and went directly to the next car where Mrs. Barnes was awaiting on him. As he passed between cars he noticed the rain had stopped. When David arrived Mrs. Barnes stood in her doorway talking to a black man dressed in a stylish white linen suit with a white straw hat in hand. Her left hand twirled her locks while she moistened her lips. As David walked up, she giggled like a shy school girl.

“My dear Mrs. Barnes,” David murmured, “I’m so glad you waited for me.”

“Hmm?” She glanced at him but returned her attention to the man in the white linen suit.

David glared at the man who stole the interest of his lady. He had the strange feeling he had seen this guy before; not only once, but many times even in that same suit. David pulled out his cigarette case, extracted one and smiled at the stranger. “Have you a light?”

“But of course.” He pulled out a silver lighter and lit the prince’s smoke.

“Have we met before?”

“Heavens no,” the stranger replied with a distinctive Bahamian accent. “You are a great gentleman, and I a mere colonial.”

“You look so familiar,” David pressed. “The man I met had one of those dreadful diseases. I hope it wasn’t you, and if it were, I hope it has cleared up.”

“Oh.” Mrs. Barnes’ eyes fluttered. She looked at both men, stepped inside her room and shut the door.

David smiled. “So sorry about that.”

“Think nothing of it.” The man bowed. “Such are the fortunes of romance.” He turned and sauntered away.

“Rapping on Mrs. Barnes’ door, David whispered, “Surely, my dear, you didn’t mean to turn me away as well.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Fifty-Three

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Stanton selects Duff, an AWOL convict,to impersonate Lincoln. Duff forms his own opinions about cabinet members.

Leaning back in his chair, Duff relaxed, confident of handling the Cabinet meeting. He was learning to deal with the egos of all the self-important men around the table. He liked some more than others. Attorney General Edward Bates reminded him of himself, little formal education and even less pretension. Duff still mourned the death of Interior Secretary Caleb Smith, a Midwesterner like himself. Smith’s replacement, John Usher, was a mystery to him. Since Stanton had recommended him, Duff did not to trust Usher.

“Mr. President, the gallant men of Maine should receive special commendation for their defense of Little Round Top yesterday,” Stanton said. “They saved Gettysburg from falling to the rebels.”

Absolute loathing covered Duff like a cold, wet wool blanket, and he remembered that sensation from his days prior to the first battle of Manassas. As much as he was choked with fear at the battle and as much as he was smothered by terror when he was captured, Duff felt even stronger emotions toward Stanton, who was adjusting his pebble glasses on his little nose. Duff nodded in acknowledgement of Stanton’s announcement but said nothing. He learned this was the safest response to any comment during a Cabinet meeting.

“The latest telegraph reports indicate today’s events should be the most pivotal since the second Manassas,” Stanton continued.

“Ah, fireworks for the Fourth of July,” Duff replied.

Laughter filled the room and boosted his self-esteem and eased his hatred toward Stanton. Among the others around the table, only one merited Duff’s respect: Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. He had to be careful not to be too friendly. The real Lincoln found Welles senile and altogether ludicrous in his large, ill-fitting white wig. Duff, on the other hand, found Welles to be profoundly wise.

“When was the last wire received?” Seward asked.

Duff did not trust Seward, whom he found hard to decipher; in other words, he could not tell if Seward believed him to be Lincoln.

“Wires within the last hour indicate Lee’s forces appear ready to advance on the center of General Meade’s line,” Stanton replied.

“Is this necessarily a bad thing?” Chase intoned.

Chase evoked mere disdain from Duff, who saw him as a sanctimonious fool. He did not worry if Chase realized he was not Lincoln, because Chase never looked him in the eye or listened to what he said, as though Duff were inconsequential.

“We don’t know at this time,” Stanton said.

Most of all, Duff hated Stanton for his contemptuous attitude Stanton of Alethia, whom he had grown to love over the past year. Duff hesitated to tell her, because then he would have to tell her his secrets, and if she learned of all the horrible sins he had committed, she would surely hate him.

“Will you keep us informed?” Welles asked.

“Of course.” Stanton smiled with condescension.

“I was talking to Mr. Lincoln,” Welles retorted.

“Everyone at this table has access to the telegraph wires at the War Department,” Duff said, noticing the grimace on Stanton’s face.

“I know that.” Welles nodded. “I just wanted to hear it from you. Sometimes it becomes a bit weary, learning official war news from Mr. Stanton.”

“Mr. Welles, may I remind you I’m the secretary of war; therefore, by definition, all information concerning the war should come through me.”

“Forgive me, Mr. Stanton, but as attorney general,” Bates interjected, “it’s my obligation to remind you that the Constitution names the president as commander in chief of the armed forces, therefore superseding you as the ultimate authority on releasing war news.”

“I stand corrected.” Stanton pursed his Cupid’s bow lips.

Duff could hardly restrain the smile creeping across his lips; instead, he surveyed the room, trying to look wise. No one seriously doubted he was president, he decided, except Stanton.

On his staff, the only person who might suspect something was Nicolay, so Duff had sent him on a special mission to Colorado. With any luck, the war would end by the time he had returned. While Duff never thought himself to be bright, he prided himself on detecting intelligence in others, and he deemed Nicolay one of the smartest men in Washington, which made him dangerous.

“Mr. Hay, do you have all this commotion on paper?” Duff asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“And it was all clear as mud, correct?”

Hay laughed and nodded his head.

He was a good boy, Hay was, but not as bright as Nicolay, Duff thought. Perhaps he was as smart as Nicolay, but he was so preoccupied with pretty women and strong liquor that his keener senses were unnaturally blunted. Hay did not consider it strange that Duff sent him to a bookstore to buy a copy of Rose Greenhow’s prison memoirs, My Imprisonment and First Year of Abolitionist Rule in Washington, not questioning why President Lincoln would be interested in a book written by a rebel spy.

“Is there any other business?” He looked pointedly into the eyes of each Cabinet member. When no one spoke, Duff sighed. “Then, let us adjourn to prepare for Independence Day.”

FIFTY-FOUR

Burly Chapter Sixteen

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. But mama died one night. Papa decided sister Callie should go live with relatives. She came home for a happy Christmas.)

The bittersweet Christmas soon faded in Herman’s mind as the months lengthened into years. Visits from Callie would become less frequent because Uncle Calvin had gotten a new job in Houston and about to move the family from Texarkana. When Uncle Calvin, Aunt Joyce and Callie came for their last visit before the move, Callie and Herman exchanged easy lies about how Houston wasn’t that far away and they would see each other often. The truth was too painful. At least Tad didn’t wait for Callie to hug him this time, which made Herman feel a little bit better. But Tad was almost seventeen and far too old to act silly and stubborn around a sister he might never see again. Even papa broke away from his long, sorrowful stares across the prairie to give Callie a warm hug and a kiss on the cheek. He even shook Uncle Calvin’s hand and gave Aunt Joyce a shy hug.

“I’m sorry to take your girl away like this,” Uncle Calvin explained in a sad sort of way. “But they’re building like crazy down there and construction’s the ground floor job, if you know what I mean.”

“Sure, Calvin,” papa said as friendly as his continuing grief would allow him.

“It’s a risk, I know,” Aunt Joyce added, “but if Calvin can hit it big that’ll mean a better education for Callie and the boys.”

“Yes,” Uncle Calvin emphasized. “We’re not just looking after the girl but all the children. If I can help them get on better, I want to.”

Papa stiffened. “The boys will do all right.”

“Sure, I know they will,” Uncle Calvin said as an apology.

Then they were gone. Tad grumbled about how Uncle Calvin was acting uppity and that they didn’t need any help.

“Calvin’s a good man,” papa rasped. “He means good by us all.”

“Yes, papa,” Tad whispered.

Herman was confused and excited by what Uncle Calvin said. Up until now he had not given much thought about what was going to happen when he grew up. But he was eleven years old and such thoughts were creeping into his mind and scaring him.

“What will happen to me?” Herman asked Burly late that night.

“You’re going to grow up,” Burly said.

“But what will I be when I grow up?” Herman persisted.

“A man,” Burly replied.

“But—“

“Whatever you become,” Burly interrupted him, “you will always be Herman. And being Herman is a wonderful thing.”

Herman hugged him. “Thank you, Burly.” He paused and noticed his bear’s little burlap face was turned down. “Are you sad, Burly?”

“I’ll never see my mother again,” Burly said.

“And I’ll never see my wife again,” Burly Senior whispered from across the room.

“Oh,” Herman replied as though suddenly realizing something. “You have lost your mother today and that makes you very sad. I didn’t think of that. All I could think have was my own problems. I’m sorry.”

“That’s all right,” Burly assured him. “Most people are like that. They never stop to look at things from the way other people look at them.”

“But you’re better than most,” Burly Senior added. “In fact, you’re doing a pretty good job at seeing the world as your father and your brother see it.”

Herman sighed. “Sometimes I wonder if I do. I don’t really know how Tad feels most of the time.”

“Take it from me,” Burly Senior offered. “He’s very sad. A very lonely, scared little boy he is.”

“How can you tell?” Herman asked.

“By the way he is squeezing me right now.”

When spring came and the wildflowers were coloring the hills everywhere, Herman noticed Tad seemed happier and spent less time home after all his chores were done. He was beginning to have friends. Herman was happy for him, for he still didn’t have many children from his class who were his friends so he knew how Tad felt.

“Don’t worry,” Burly said one afternoon after Tad had run off to play with his new buddies. “Someday you will have boys your age to be your friends.”

“But why don’t they like me now?” Herman asked.

“I like you now,” Burly replied.

Herman smiled and hugged his little burlap friend. “I know you do, but what can I do to make the boys at school like me?”

“If you have to do anything to make them like you then they aren’t really going to be your friends anyway.”

Sighing, Herman gave Burly another hug. After school was out for the summer, Herman changed his mind about Tad’s friends because they began to spend more time at the farm and Herman saw what they were really like. One of them, a tall, stringy-looking boy with lots of freckles and straw-like hair, liked to tease Herman for being too short and not being able to run very fast or play baseball very well. He made Herman feel like he was dumb sometimes when he would pull a mean trick on him. His name was Leonard. The other boy, Stevie, was shorter than Tad but bigger and broader. He sulked about all the time and didn’t say much, except an occasional threatening grunt. Steve always looked at Herman as though he would like to beat him up. Of course, both boys would straighten and be polite when papa walked by. Papa may have been skinny but he was strong and he acted like he might explode into a violent temper tantrum at any moment.