Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Stanton selects Duff, an AWOL convict,to impersonate Lincoln. Duff forms his own opinions about cabinet members.

Leaning back in his chair, Duff relaxed, confident of handling the Cabinet meeting. He was learning to deal with the egos of all the self-important men around the table. He liked some more than others. Attorney General Edward Bates reminded him of himself, little formal education and even less pretension. Duff still mourned the death of Interior Secretary Caleb Smith, a Midwesterner like himself. Smith’s replacement, John Usher, was a mystery to him. Since Stanton had recommended him, Duff did not to trust Usher.

“Mr. President, the gallant men of Maine should receive special commendation for their defense of Little Round Top yesterday,” Stanton said. “They saved Gettysburg from falling to the rebels.”

Absolute loathing covered Duff like a cold, wet wool blanket, and he remembered that sensation from his days prior to the first battle of Manassas. As much as he was choked with fear at the battle and as much as he was smothered by terror when he was captured, Duff felt even stronger emotions toward Stanton, who was adjusting his pebble glasses on his little nose. Duff nodded in acknowledgement of Stanton’s announcement but said nothing. He learned this was the safest response to any comment during a Cabinet meeting.

“The latest telegraph reports indicate today’s events should be the most pivotal since the second Manassas,” Stanton continued.

“Ah, fireworks for the Fourth of July,” Duff replied.

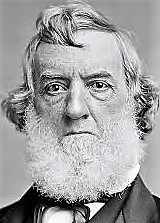

Laughter filled the room and boosted his self-esteem and eased his hatred toward Stanton. Among the others around the table, only one merited Duff’s respect: Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. He had to be careful not to be too friendly. The real Lincoln found Welles senile and altogether ludicrous in his large, ill-fitting white wig. Duff, on the other hand, found Welles to be profoundly wise.

“When was the last wire received?” Seward asked.

Duff did not trust Seward, whom he found hard to decipher; in other words, he could not tell if Seward believed him to be Lincoln.

“Wires within the last hour indicate Lee’s forces appear ready to advance on the center of General Meade’s line,” Stanton replied.

“Is this necessarily a bad thing?” Chase intoned.

Chase evoked mere disdain from Duff, who saw him as a sanctimonious fool. He did not worry if Chase realized he was not Lincoln, because Chase never looked him in the eye or listened to what he said, as though Duff were inconsequential.

“We don’t know at this time,” Stanton said.

Most of all, Duff hated Stanton for his contemptuous attitude Stanton of Alethia, whom he had grown to love over the past year. Duff hesitated to tell her, because then he would have to tell her his secrets, and if she learned of all the horrible sins he had committed, she would surely hate him.

“Will you keep us informed?” Welles asked.

“Of course.” Stanton smiled with condescension.

“I was talking to Mr. Lincoln,” Welles retorted.

“Everyone at this table has access to the telegraph wires at the War Department,” Duff said, noticing the grimace on Stanton’s face.

“I know that.” Welles nodded. “I just wanted to hear it from you. Sometimes it becomes a bit weary, learning official war news from Mr. Stanton.”

“Mr. Welles, may I remind you I’m the secretary of war; therefore, by definition, all information concerning the war should come through me.”

“Forgive me, Mr. Stanton, but as attorney general,” Bates interjected, “it’s my obligation to remind you that the Constitution names the president as commander in chief of the armed forces, therefore superseding you as the ultimate authority on releasing war news.”

“I stand corrected.” Stanton pursed his Cupid’s bow lips.

Duff could hardly restrain the smile creeping across his lips; instead, he surveyed the room, trying to look wise. No one seriously doubted he was president, he decided, except Stanton.

On his staff, the only person who might suspect something was Nicolay, so Duff had sent him on a special mission to Colorado. With any luck, the war would end by the time he had returned. While Duff never thought himself to be bright, he prided himself on detecting intelligence in others, and he deemed Nicolay one of the smartest men in Washington, which made him dangerous.

“Mr. Hay, do you have all this commotion on paper?” Duff asked.

“Yes, sir.”

“And it was all clear as mud, correct?”

Hay laughed and nodded his head.

He was a good boy, Hay was, but not as bright as Nicolay, Duff thought. Perhaps he was as smart as Nicolay, but he was so preoccupied with pretty women and strong liquor that his keener senses were unnaturally blunted. Hay did not consider it strange that Duff sent him to a bookstore to buy a copy of Rose Greenhow’s prison memoirs, My Imprisonment and First Year of Abolitionist Rule in Washington, not questioning why President Lincoln would be interested in a book written by a rebel spy.

“Is there any other business?” He looked pointedly into the eyes of each Cabinet member. When no one spoke, Duff sighed. “Then, let us adjourn to prepare for Independence Day.”

FIFTY-FOUR

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Fifty-Three

Leave a reply