If truth be told, I’ve lived in Ireland all me life and have kept a most peculiar secret. Since I’m away from home among strange and foreign peoples, I’ll share it with ye.

Me best friend in all the world is a leprechaun.

Now laugh if ye must, but it’s the God’s honest truth. It began when I was a wee lad in—oh, I can’t tell ye the name of me village, because ye be likely to go there and look for me best friend’s gold, and I can’t have that. Let me just say I live in a tiny town in a lovely meadow surrounded by tall trees and awesome hills. Ha! The whole of Ireland looks like that, so what good does that do ye! As I was sayin’, I was a wee lad without any friends and no prospects for any kind of prosperous life. Me da had long since died, and me ma had to take in laundry to feed and clothe us children.

Me ma had sent me out into the woods searchin’ for berries when I first came upon the little man. No more than three feet he was, and not much shorter than meself. Bein’ a lad who had no such knowledge of leprechauns, I mistook him for another child.

“Hello there,” says I. “Do you want to play?”

“Off with ye, ye little devil!” the leprechaun says in a mean and nasty voice.

I’ll be not ashamed to tell ye, I sat right down on the ground and began to cry like a baby.

“Why don’t nobody want to play with me?” I says in a bawl. “Am I such a terrible mortal being that I must be shunned me entire life?”

Now the little man took a step back and then twisted up his face. “Bah! It’s all just a trick to get me pot of gold.”

“I don’t want a pot of gold. I just want a friend.”

I must have sounded like the most pitiful creature he had ever heard in his life because he took a few steps towards me.

“Don’t ye know who I am, child?”

When I lifted me little tear-stained face, I saw that what was standin’ in front of me wasn’t no child at all, but a shriveled up old man. If I had had any sense about me at all, I’d jumped to me feet and run home.

He put his hands out between us. “Don’t look into me eyes!”

“No, sir, I won’t,” I says in reply. “To tell ye the truth, I’m a mighty shy lad and don’t like lookin’ into no body’s face at all.”

The little man slowly lowered his hands. “That’s good, because if ye did stare into me eyes I’d beholden to take you to me gold.”

I wiped the tears from me eyes and rubbed me nose on me sleeve. “Why do ye keep talkin’ about a pot of gold? I don’t think nobody in Ireland has a pot of gold, and that’s the God’s honest truth!”

His wee mouth fell open. “The saints preserve us, I do believe ye don’t know who I am.”

“Ye are a mean wrinkled up old man, and I want nothin’ to do with ye!”

“Ain’t ye never heard of leprechauns, lad?”

“No.” I was about to get to me feet and run away.

“What kind of a da would ye have that would not tell ye of leprechauns?”

“Me da is dead! And me ma must wash clothes all day and all night to put food on the table! Now, go leave me alone!”

“Oh, child, I didn’t know.” He pulled a leather pouch from his pocket and took out a gold coin. “Now why don’t ye take me gold coin? It should make it all better.”

Now I was really mad. I stood and kicked dirt at the little man. “And how do I know it’s a real gold coin? And if it is real, then one of the O’Leary boys will steal it from me before I get home.”

He put the coin piece away and put his arm around me waist and said, “What brings ye to the woods, lad?”

“Me ma craves some berries for supper. She sent me to look for some.”

“Well, ain’t ye the luckiest boy in all of Ireland. I happen to know where the best berries grow.”

And he showed me where they were. And the next evenin’ he showed me where the prettiest heather grew so I could take a bundle to me ma. Then he said he liked to use heather to make some poteen. I bet ye don’t know what poteen is. It’s what you call in this country moonshine. I told him quite honestly that I didn’t think me ma would care much for poteen.

He laughed and I laughed and we had a grand old time. Over the next few years he told me exactly what a leprechaun was and why he was so jealous of his pot of gold. I kept tellin’ him that I didn’t care a thing for gold, but he just puffed on his pipe and said, “One day, lad, one day ye shall grow up and ye will care about gold then, and then we must part our ways.”

I swore to him that it wasn’t true, but he just smiled and puffed his pipe. Oh, what things he taught. I learned how to make a fine pair of shoes. I could make money for me family now. He taught me how to sing and dance. And what young lady could resist an Irish lad who could sing and dance? When I turned the ripe old age of twenty-one, the leprechaun said, “Ye are a fine strappin’ man now. Ye have a fine business and a beautiful wife. We can never see each other again.”

“Ye are just as mean and nasty as ye have ever been,” I says to him with a snort. “But ye won’t run me off as easy as that.”

The next thing I knew I felt a crackin’ pain on me head and I was out like a light. When I came to, there was one of those O’Leary boys—Fergus, the meanest one of them all—staring into the eyes of the leprechaun, and sure as could be he was forcing me wee little friend to take him to his pot of gold. Like a sure footed deer I followed them to a cave. And when that devil Fergus O’Leary came out holdin’ me friend’s pot of gold, I jumped on his back and rassled him to the ground. We was tradin’ blow for blow until I found meself on my back with Fergus O’Leary standin’ over me with a giant log, about to bash me to death. Then, poof, a cloud of smoke and all that was left of Fergus O’Leary was a teeny green frog.

I saw the leprechaun standin’ there, with his arms still outstretched, pointing at the frog that once was Fergus. I stood, picked up the pot of gold and handed it back to me friend. He took it and stared a long time at me.

“But ye could have kept the gold, and there was not thing I could have done to stop ye.”

Smiling, I says, “Are ye daft, man? What good is a pot of gold if you don’t have a friend?”

Monthly Archives: March 2018

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty-Four

Previously in the novel: Novice mercenary Leon fails in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury because of David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer. Wallis, in quick succession, dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol and marries Ernest. In the meantime David has an affair with Freda Ward and Thelma Furness. MI6 wants him to seduce Princess Stephanie of Austria.

A month later Joachim von Ribbentrop invited David to a party at his elegant suite at the Ritz Hotel on Piccadilly across from Green Park and down the street from Buckingham Palace. Neither Freda nor Thelma were available so the prince went stag. As he exited his Ace roadster outside the hotel, a beggar woman walked up and extended him an apple. He waived her off.

“Oh, bugger you, David,” she rasped. It was the MI6 contact. “The Austrian princess is in the house. Don’t muck it up.”

As he rode the elevator to the von Ribbentrop apartment, David lit a cigarette and mused how much a bore all this was. He was joking with himself, of course. He loved to crack wise with himself. Once inside, the attendant took his hat and overcoat. David scanned the room and identified a new woman in attendance. Good posture accentuated her height; shiny dark hair surrounded piercing eyes, and rouged lips screamed to be kissed. It had to be Stephanie. He was sure and took decisive steps in the other direction, seeking out some middle-aged, paunchy, balding diplomat for a boring conversation. One can never be too obvious when seducing a new woman.

Within a few minutes, David felt a tap on his shoulder. When he turned he saw Lady Elvira Chatsworth. Oh hell. He had no time for her now.

“Elvira, what a lovely surprise,” he purred, leaning in to kiss her cheek. “I don’t think I’ve seen you since that trip to Shanghai. You know, I’ll always consider that crossing to be one of the happiest moments in my life.”

She giggled. “My husband is out of town for two weeks.”

“What a shame. So am I.”

After another quick peck, David slipped away toward the foyer to retrieve his coat and hat. This was not working out the way he anticipated. Perhaps he was playing too hard to get. Ah well, he told himself, other opportunities would present themselves.

“Your highness,” a deep male voice called out, “I hope you are not leaving so soon.”

David recognized it to be his host Von Ribbentrop. He turned and smiled. “Of course not. I just saw someone on the other side of the room I didn’t know and wanted to strike up a conversation.” He extended his hand. “And how are you, Herr Von Ribbentrop?”

“Never better.” As Ribbentrop shook hands he made a proficient bow and clicked his heels.

David tried not to roll his eyes. He hated men who clicked their heels. He felt as though they were about to break out in a tap dance. Instead, he lifted his head to survey the room.

“And where are your lovely wife and children?”

“Ah. My wife Anna is probably busy in the kitchen attending to the final details of the dinner. She is such a hausfrau. And the children are back in Berlin with Anna’s aunt. London can be such a tiresome place for German children.”

“Is that so? English children don’t seem to mind it so much. Of course, they’re used to it.”

“Quite so.” Von Ribbentrop gently touched David’s elbow. “Actually, the reason I came over is because I wanted you to meet my guest of honor, Princess Stephanie Hohenlohe.”

“Who?”

“I would have thought a man of your reputation would have heard of Princess Stephanie of Austria.” His index finger smoothed through his moustache.

“Oh, that Princess Stephanie. Show her to me.”

They wriggled through the crowd to Stephanie who was holding court in front of a battery of dashing young men, who were enthralled by her every word. Ribbentrop tried to intervene to introduce the prince. She gracefully held up a gloved hand.

“Please. I must finish my story.”

David smiled as he observed Ribbentrop flushing. A moment later, the attending beaux applauded politely, and Stephanie turned, flashing a brilliant smile.

“Yes. May I help you?”

“I would like to introduce His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales,” Ribbentrop said with the utmost pomp and circumstance.

Stephanie let forth with a rapid succession of sentences in German. She stopped abruptly and a hand went to her cheek. “Oh. I’m sorry. You’re British, aren’t you, and you don’t speak German, do you?”

Without a pause, David replied in fluent German. “You see, it is my mother tongue.”

“My, you are clever.” She smiled again. “So how may I help you?”

“Stephanie, I told you. This is the future king of England,” Ribbentrop replied in a measured tone.

“Then you don’t need my help, do you?” She nodded toward David.

“Oh, you would be surprised,” David replied, focusing his squinty eye on the bodice of her gown.

The doors to the dining room opened, and Anna Von Ribbentrop appeared and announced, “Dinner is served.”

“Oh, thank God,” Ribbentrop muttered as he began prodding his guests to the table.

David extended his arm, and Stephanie took it. Remarkably, they were seated next to each other and exchanged witty repartee for the next two hours. And then he proved his excuse to Elvira Chatsworth to be true by driving the Austrian princess out of the city to Fort Belvedere.

“We just finished the renovations last week. You can still smell paint. Full staff. They’re from one of Mama’s places up north. They know their jobs.”

It was after midnight when they arrived. He unlocked the door and escorted her in.

“Be quiet,” he whispered. “The servants have retired and if they hear us, they will be tedious in their efforts to attend us.”

“But I can’t spend the night,” Stephanie protested. “All I have, in clothing, is what I have on. Whatever shall I wear to bed?”

David took her into his arms and kissed her on the mouth. “We’ll think of something.” As he led her upstairs, he added, “You can send for your things in the morning. By the way, where are you staying?”

“Dorchester Hotel in Mayfair.”

“Ah, not far from the Ritz. That will make directions for my man easy.” He paused to grin. “After all, you will be staying for a couple of weeks.”

She stopped on the last step before reaching the second landing. “Two weeks! Why would I want to stay two weeks?”

“You do want to get to know me, don’t you?” David took her hand and kissed it. “It takes a good two weeks of constant companionship to know me extremely well.”

Stephanie took the last step to the bedroom floor. “As long as you put it that way.”

Don’t Want to Die Before I Die

There I was under my usual cluster of trees at the annual art festival in my hometown sketching charcoal portraits of children for a donation to my tip basket. Sometimes I made enough to pay for a whole month of going out for coffee with the guys.

I don’t right remember how long I’ve been doing this. Let’s see. The festival’s been going on for thirty-six years. I didn’t start drawing until after I retired so that makes—well, too many years to figure out. The folks who put this shindig together have always put me on the row with vendors with local produce, the dog cremation company, the historical society, the man who sells plants that eat bugs and politicians handing out petitions to be signed.

The real artists and craftsmen are on the other side of the park, and that’s all right with me. Nope, never won a ribbon. Wouldn’t know what to do with it. The house is filled with my wife’s clutter, and it’s been two years since she died.

What I get a kick out of are the parents who force their kids to sit in my chair long enough for me to draw them. Basically, all the little boys look the same. Just like the girls. The mamas don’t care. They can see the resemblance, and that’s all that matters. They toss a dollar into my basket and move on.

Some days are busier than others which is fine. If I draw too many pictures in a day, arthritis plays hell with my fingers all night long and I can’t get a decent sleep. My fellow old men will sit in my chair to rest up before they finish their walk around the circle. A few want to bend my ear about local politics and others just stare in the distance at something, then without a word they stand and walk away.

A handful of mamas through the years have brought their children for a drawing each festival. They say it’s saving their kid’s childhood, picture by picture. That’s kinda nice. I also like to watch the mamas watching their boys and girls squirm in the chair until I’m finished.

On the last day of the festival this year a woman—she must have been as old as I am but I couldn’t tell for sure because she wore too much makeup—walked down the path toward me. She held the fingers on her right hand like she was holding a cigarette. I figured she had smoked for years until her doctor told her she would die of cancer if she didn’t stop. She beat the nicotine habit but she couldn’t keep her fingers from assuming their long-time pose of sophistication. Smoking used to be considered very sophisticated back in the old days.

I became aware of her standing behind me as I finished a charcoal rendition of twelve-year-old boy. The mother burbled something about how she was so glad to have this because next year he’d start changing into a teen-ager and never be her little boy again. She walked off without putting anything in my tip basket.

The old broad leaned into my left ear. I could smell her lipstick. It had to be red; red lipstick had a smell all of its own.

“You do know you’re not really talented, don’t you?”

I turned and smiled. “Of course. If I was really talented, I wouldn’t be in this one-horse town drawing pictures for free.”

Her lacquered fingertips went to her rouged lips as though she wanted to puff on her imaginary cigarette. Boy, I thought, she really missed smoking.

“Then why do you even bother?”

“Because when I give it up, I start to die.” I shrugged. “Oh, I know I’m dying.” I patted my chest. “But if I stop things I like just because I’m not really good at them, then my soul begins to die.” I paused to smile my best little boy smile. “And I don’t want to die before I die.”

Lincoln in the Basement, Chapter Forty-Eight

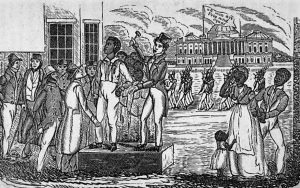

Phebe and her family were sold at auction

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Janitor Gabby Zook by accident must stay in the basement too. Cook Phebe sees all and tries to tell butler Neal what she thinks.

“Why would I get mad?” Neal demanded of Phebe.

“Because you’re always mad, especially at the white folks,” Phebe said. “I see it in your eyes. You really hate them, and I don’t get it. I mean, you’re born free—”

“Yes, I’m free, for what good that does me,” he interrupted her angrily, spitting on the floor.

“I—I don’t understand…”

“I was born the son of a freeman in the city of Boston. He was the son of a freeman, all in a long line of tutors, teaching French to Boston merchants who traded with Haiti and other points in the Caribbean.”

“You speak French?”

“Yes. So what?” He paused. “My mother, as a child, came to Boston in the middle of the night in her mother’s arms, a slave from a Virginia tobacco plantation.”

“A runaway slave,” Phebe murmured.

“She grew up cooking and sewing in wealthy New England homes. That’s where she met my father, who tutored the master of the house. They married, found a comfortable apartment, and had me. I was supposed to be the one to climb the next rung on the racial equality ladder, perhaps the ministry, law, or medicine. But it was not to be. Ever heard of the Fugitive Slave Law?”

“Yes.”

“Slave owners tracked down runaways in Free states, and local authorities and ordinary citizens had to help.”

“So they came for your grandmother?” Phebe asked.

“No. She was dead. They came for my mother. My grandmother stole my mother from the farmer, who wanted her back.” Neal paused. “And her offspring. Any child from her womb was his property too.”

Phebe jumped when she realized he was talking about himself.

“I remember when they took my mother. Her cries woke me up. At first my father was angry, shouting at her. He didn’t know he’d married a runaway. He stopped yelling when she said she didn’t remember anything before life in Boston kitchens. White men banged at the door, demanding they come out. My father took me from my bed and pulled down the attic ladder. He told me to be quiet, and my mother kissed me, her lips still moist from her tears. He had just closed the attic ladder when the slave catchers broke through. I cried as I heard them drag her away. I never saw her again. ”

“I haven’t seen my mother in a long time either, but I still have hope.” Immediately Phebe wished she had not spoken.

“You’ve been bought and freed, all legal. You got hope because you don’t know no better. No, I don’t have to worry about being taken South anymore. But I don’t have a chance for a profession now.” Neal sighed and mellowed. “When my father told me he’d arranged a job for me in Washington, I thought it might lead to something, but when I arrived at the White House, they sent me to the basement to be a butler.”

“Butler is a good job,” Phebe said, trying to be encouraging. “Why, on the plantation the butler was—”

“This ain’t the plantation, girl,” he interrupted. “This is the world. This is life. We may be free, but we ain’t white.”

“I know.”

“Well, tell me,” he said. “Who do you think the woman in the billiards room is?”

“I was talking to Mrs. Keckley. She’s the lady who sews the Mrs. Lincoln’s clothes. I said to her things had been odd for the last few months. She got real quiet, looked around, then pulled me closer and made me promise not to tell anyone.”

“Not to tell what?”

“She said when she went to fit the Mrs. Lincoln for a new dress the middle of September she saw right off something was different. The Mrs. Lincoln was bigger, across her chest. The missus looked real flustered, Mrs. Keckley said, laughing and rambling on about gaining too much weight. When a woman gets fat, it goes on her butt or hips or belly first.”

“Just what are you trying to tell me?”

“I’m still scared how you’ll take it.”

“You still think like a slave.” Neal snorted.

“Well,” Phebe said softly. “It’s all I know.”

Her owner was Pierce Butler, whose grandfather authored the fugitive slave clause in the United States Constitution. Her earliest memories were of being held by his beautiful wife, who was rumored to be a fancy actress from England. Then the master’s wife had gone away. When Phebe asked about her, she was told to hush and mind her own business. The rest of her childhood was uneventful, though filled with hard work, until all the slaves on the plantation were loaded on a ship and taken down the Altama River to Savannah, where they were taken to the Kimbrough Race Track during a torrential downpour. Men prodded them, looked in their mouths, tested their muscles, and stood back, cocking their heads in judgment.

Earlier in the day she had watched her father being led away, and later her mother, her eyes filled with tears. Feeling all was lost, Phebe used all her willpower to keep from crying. Soon it was her turn to stand on the block, and a miracle happened. When the bidding was over, Phebe met her new owner, Mortimer Thompson, a reported for the New York Tribune, who said she would be freed as soon as they arrived in New York City. But what will I do? Phebe had asked him; How will I support myself? He had taken her hand.

“I know an old friend of yours,” he said.

Her old friend was Mrs. Butler, whose stage name, Fanny Kemble, was in large letters across a theater marquee.

“What a pretty face,” Mrs. Butler said with a gush as she patted Phebe’s cheeks.

“Thank you, ma’am,” Phebe said shyly.

“I wish I could afford to employ another maid, but I can’t.” When Phebe’s face fell, she added, “But don’t give up hope. I’ve friends all over, here in New York, in London, and in Washington.” She smiled at Phebe. “How would you like a job in the Republican administration? I’ve many contacts with abolitionists.”

By the time the whirlwind had ended, Phebe lived in the basement of the Executive Mansion, cooking meals and witnessing the nation’s business first hand. Which brought her back to Neal’s question about who she thought was in the billiards room. Before she spoke, Phebe realized she risked not only Neal’s ridicule, but also the loss of her job—a step backward toward slavery she did not want to take.

“I don’t know.” She walked to the door and opened it. “Now that I think about it, there’s nothing wrong, nothing wrong at all.”

Burly Chapter Twelve

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. A black family moved into the barn to help them pick the cotton. Mama continued to have dizzy spells. And then one night, when a turtledove got into the rafters, mama died.)

The next few hours floated by Herman as though he were dreaming, but he knew it was not a dream. His mother was dead. From the moment Callie sat in that chair and cried Herman felt as though he had been captured in a giant bubble, a bubble that somehow made him invisible to the people rushing around him; a bubble, however, that was crystal clear and allowed him to see exactly what was being done and what was being said; and, finally, and dreadfully, a bubble that had somehow numbed him so that he didn’t feel his sister’s sorrow, his brother’s anger and papa’s total despair.

“Mama’s dead,” Callie whispered again and again, each time getting softer and softer.

Tad walked to the bedroom and peeked in.

“Get out of here!” papa roared. “Haven’t I told you not to disturb your mother while she’s resting?”

Tad backed away in fear, then, turning and taking stock of what was happening, bolted for the door. Herman watched him leave but didn’t ask where he was going. He couldn’t ask. He couldn’t make his voice work at all.

A few minutes later Tad was back with a neighbor, a tall, heavy man with grayish white hair. Hovering at the door were the Johnsons murmuring and whispering. The neighbor went into the bedroom.

“Mr. Horn?” he asked.

“Go away!”

“The boy here says Mrs. Horn’s passed on.”

“She’s fine! Go away!”

“No, no. She’s dead,” Callie whimpered. “Her eyes, they’re just staring. And—and she’s not breathing at all.”

“Mr. Horn, the children—“

“Go away or I’ll blast your head off with my shotgun!”

The neighbor turned to Tad and shook his head. “Your papa’s gone loco, boy. I got to get some help. You stay here with your brother and sister.”

The tall man was almost out of the door when Tad said, almost to himself, “Papa’s not loco. Don’t you call my papa loco.”

And the turtledove kept on cooing. Somewhere in the recesses of Herman’s mind the thought occurred to climb the ladder to the loft to try to catch the turtledove and take it outside so nobody else would die that night. His body wouldn’t move.

Several minutes later the neighbor returned with the county sheriff—Herman recognized him because he always patted him on the head and gave him a penny for candy. Right behind them was the doctor—he knew him from the time papa broke his arm falling from the barn loft and the doctor came to set it.

“He’s in there,” the neighbor whispered.

Tad stiffened as though guarding the door. “He’s not loco,” he mumbled.

The sheriff, not as tall as the neighbor but bigger around the middle and wearing a gun and holster, strode across the rough wooden floor.

“Woody?” he bellowed out in a shaky but friendly voice. “It’s Pete. I got the doc here to look at your Mrs.”

“Go away!”

“Now, Woody, Mr. Cochran here says Opal’s passed away, and the doc’s got to see her.”

“He’s not loco,” Tad mumbled, blocking the sheriff’s way into the room.

The sheriff gently moved Tad to one side. “I know, son. Now get out of the way so we can help.”

“You tell Cochran to mind his own business!” their father yelled.

The sheriff looked in the door then glanced back out at the doctor. “Yeah, doc. She’s gone.”

“I said to get out of here!” Papa screamed as he flew from the bedside to pounce on the sheriff who had a hard time throwing him off and down on the floor.

“Doc! Do something!” the neighbor yelled.

Quickly the doctor opened his bag and began to fix an injection of some kind while the neighbor helped hold down papa. When Tad saw what the doctor was doing he ran over and tried to stop him.

“Don’t you hurt my father!”

The neighbor wrapped his arms around Tad as the doctor gave papa the injection. “Don’t worry, boy. The doc’s just giving him something to help him sleep.”

“No! No!” Tad screamed.

Soon papa fell limp from the injection, and Tad stopped fighting the neighbor who let him go. Tad crept into the corner nearest the bedroom door and huddled there, like a shivering, scared puppy dog. The neighbor and the sheriff carried papa into the bedroom and carried mama out.

The sheriff glanced at Mrs. Johnson. “Get the children to bed.”

Mrs. Johnson looked at Tad crouched in the corner and then whispered to her husband, “Leave him alone. He can take care of himself.”

She walked over to Callie who was sniffing and wiping away the last of her tears. “Will you be all right, honey?” she asked.

Callie nodded and looked up to smile bravely. Mrs. Johnson was about to move on to Herman when she heard the cooing of the turtledove in the rafters. She motioned to her husband.

“Get that thing out of here.”

Then she walked over to hug Herman who couldn’t help but hug back and break into tears.

“That’s all right, baby. You just go right on ahead and cry your eyes out. That’s what the Lord gives us tears for, when that cross becomes just too much to bear.” After a moment she moved him to the ladder leading to the loft. “Now you get up there and try to get some sleep. There’s going to be some long hard days ahead for you, child, and you’ll need all the rest you can get.”

Herman found himself all alone in the loft, until he felt a scratchy rub at his elbow. It was Burly.

“I’m sorry your mama died,” he whispered. “If stuffed bears had tears, I’d cry for you.”

“Oh, Burly I didn’t mean to kill mama!”

Burly wrinkled his nose. “You didn’t kill your mother.”

Herman shook his head. “Oh no. I did. Tad and I caught that turtledove and somehow it got into the house.

Burly tried to hug Herman with his little burlap arms. “No, no, no. You did not kill your mother. That story about the turtledoves was a superstition.”

Herman frowned. “What’s a superstition?”

“A story that isn’t true but people believe in it anyway. Sometimes people know it isn’t true but they repeat it because they think it’s funny.”

“Are you sure?”

“As sure as I am of the fact you loved your mother.”

Herman hugged Burly tightly and began to cry all over again. He didn’t realize he had so many tears inside him. Finally the tears went away, and Herman drifted into a very deep sleep.

Decoding Feminine Mysticism

After all these years I think I finally decoded one of the many mysticisms of femininity. If I’m wrong please don’t tell me. I’m so satisfied with myself for understanding something new about women I don’t want it spoiled.

Going back to when I was a young man in the 1960s I was a bit confused about why some women wanted to hyphenate their names after getting married. One person explained that it was about a woman keeping her own name. But, as I thought but dared not say aloud, it wasn’t her name anyway. It was her father’s name and his father’s name before that. I didn’t actually say it because I didn’t want to come across as being a male chauvinist pig.

I even knew a woman once who had a hyphenated name whose husband hyphenated his name with hers. The trouble was that she eventually divorced him. His being so understanding got on her nerves, I think. Anyway, after the divorce he kept his hyphenated name.

Don’t get me wrong. I was all for anyone calling themselves anything they wanted. If they hyphenated every name from the last ten generations it was fine with me. I was especially all for women making equal pay for equal work. When you’re a stay-at-home dad with no other income, you become real women’s libber.

My daughter, being raised by a stay-at-home dad while mom was a probation officer, grew up to be very opinionated and independent. She didn’t even take her first husband’s name when they married. He actually volunteered to take her last name. It’s just as well that he didn’t because she divorced him anyway. He didn’t do his share of the cooking and cleaning. What’s the use of having a man around the house if he doesn’t do any housekeeping? She got a new husband now. He cleaned house, and she took his name.

Anyway, in the last few years, I noticed more women used their maiden names as a middle name, not hyphenated. My wife told me women had to do that for legal documents, like deeds and stuff. That was true, but I saw it places where it was not a legal document.

This was where my epiphany came in. The feminine mysticism became clear. I was wrong. Nothing mystical about that. But I was wrong thinking the insertion of the maiden name had to do with identity issues. That was not it. It was a love issue.

Women who identified themselves with their maiden names in the middle were giving credit to their mothers and fathers. They wanted the world to know who was responsible for who they were. It was the woman and the man of a certain name who raised her with self-esteem, values, common sense and education. I wanted to think these women were honoring their parents.

You see, men didn’t have to think about things like that because our parents got credit, or blame as the case may be, automatically because of the way society was. Leave it to women, through their mysticism, to go the extra mile to give credit where it is due.

Please don’t tell me I’m wrong.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty-Three

Previously in the novel: A mysterious man in black foils novice mercenary Leon from kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer. Wallis, in quick succession, dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol and marries Ernest. In the meantime David has an affair with Freda Ward.

In September of 1929, David found himself again handing out rosettes for prize-winning cattle, this time in Leicestershire. As he awarded best in show, the crowd broke out in polite applause. He did not know whether it was for him or the bull. Nevertheless he smiled graciously and nodded until he noticed a lovely woman standing in front who was not clapping. She seemed to be more concerned with adjusting her gloves than according him accolades for attaching a ribbon cluster to the bovine’s harness. Without stopping to speak to the local mayor, David approached her.

“My God, you are as beautiful as a movie star.”

“That’s because I am one.” She retrieved a cigarette from her hand bag. “Do you have a light?”

“Of course,” he replied, pulling out a book of matches. “Tell me about your movie career.”

After a puff, she explained, “I formed my own movie company in 1923 so I could be a star.”

“Impressive.” David smiled with interest. “What were they? Maybe I’ve seen some of them.”

“I doubt it.” She shrugged. “Making movies turned out to be such a bore.”

“What a shame. I hope you didn’t lose much money.”

“Don’t worry about it. Daddy’s rich. He’s American diplomat Harry Morgan.”

“My daddy is rich too.”

“I know. King of England. You’re the Prince of Wales.”

“And if you tell me who you are then introductions will be complete.”

“Thelma Furness, wife of Viscount Marmaduke Furness. That’s why I’m at this dreary country fair. Former wife. The ink just dried on our divorce papers.”

“Then that means you’re free for the weekend.”

Without further encouragement Thelma hopped in David’s Ace roadster and sped off to Fort Belvedere. She commented his car looked just like Victor Bruce’s auto that won the Monte Carlo Rally.

“I’m just dippy for it,” she said.

David shifted into first gear and stirred up a cloud of dust on the country road. He enthusiastically explained the renovations which were underway since his father finally agreed to give it to him.

“You won’t believe what he said when I first asked him for it,” David said with his infamous lopsided grin. “’What could you possibly want that queer old place for? Those damned weekends, I suppose.”

At that moment they turned a corner, and Fort Belvedere appeared with scaffolding half-way around it.

“I’m absolutely dippy for it,” Thelma announced.

“Don’t worry about the workmen,” he confided. “They won’t be back until Monday.

After they parked, David guided her through the front door and gave her a tour of his bedroom which lasted until the next morning. When he awoke, Thelma was gone but he smelled coffee from the kitchen. They settled into the breakfast nook for a small meal Thelma had whipped up. David decided she looked beautiful even with most of her makeup smudged away. He was about to explain his special relationship to Freda when a reflective mirrored light from the woods beyond the lily pond caught his attention.

“You know I’m quite peculiar,” he began, not knowing how to explain why he had a sudden urge to stroll through the grounds.

“Oh, I know all about Freda,” she said as she stood and collected the dishes. “And I know you’re devoted to your gardening. First thing every morning, playing in the dirt. It’s in all the social pages.” Thelma leaned over to kiss him on the lips. “You’ve been royally had, my dear. You’ve been in my sights for years.” She winked. “I love to share.”

When David first went out the door he started straight for the woods but thought better of it. He turned instead for the shed where he grabbed a few tools. He needed to make Thelma think he was going to play in the dirt. Upon arrival among the silvery birches, he recognized one of his main contacts from the MI6 headquarters. David knew this assignment must be of the highest importance.

“At first I didn’t think you saw my signal,” the man said. “Let’s take a few steps back. No need to alarm the young lady.”

“Nothing would alarm that one,” David muttered as he followed the man around one of the larger trees.

“You know about Princess Stephanie?”

“She’s from Austria, isn’t she? Married a prince or something or other and after the divorce she kept the title.”

“Very close. She was born in Vienna to Jewish parents. Her father was a dentist, a lawyer or some such that they had a bit of money but nothing to brag about. She did quite well in ballet school and became renowned for her beauty. She had an affair with Archduke Franz Salvator who impregnated her. This was a problem because he was already married. Stephanie then talked Friedrich Franz von Hohenlohe into thinking the child was his. They were married a few years and divorced. She kept the child and the title of princess.”

“I can get all this information on the cocktail circuit.” David grew impatient. “What does this have to do with me?”

“This is what concerns us. She’s kicked around Europe and most recently Germany where she has become close friends with Adolph Hitler.”

“No one seriously thinks Hitler has any chance of becoming chancellor, do they?” The more he heard, the more David wanted to get on with pruning his roses.

“Everyone is taking Hitler seriously and so should you,” his MI6 contact said in a stern voice. “We have it on good sources that Hitler wants Stephanie’s next husband to be you.”

David laughed out loud. “My God, the man is mad. Why would he want that?”

“He’s gotten the idea you’re warm to the idea of fascism in Great Britain. With an Austrian wife and the English crown, you would welcome an alliance with a Hitler regime.”

“Why would he think that?”

“The cocktail circuit you just mentioned. You’re quite popular with many right-leaning socialites,” he intoned.

“That’s just balderdash. Too much liquor. Too much philandering.”

“Oh, you misunderstand. We don’t disapprove. We want you to take advantage of this misperception to seduce Princess Stephanie. Cultivate her as a source of information in the coming years.”

“So you want me to bed her.” He gazed back at the house. “Well, I hope she’s as beautiful as they say.”

The Nature of Tears

Two years have passed, and I yet have shed a tear over the death of my wife Janet. The other night I watched the Oscars and looked over to her side of the sofa and said aloud what I know what she would have commented on each and every dress. I wrote a play as a benefit for the local free clinic because as a probation officer Janet told her people to go there for help. I still wear my wedding ring. But not a single tear.

Two years have passed, and I yet have shed a tear over the death of my wife Janet. The other night I watched the Oscars and looked over to her side of the sofa and said aloud what I know what she would have commented on each and every dress. I wrote a play as a benefit for the local free clinic because as a probation officer Janet told her people to go there for help. I still wear my wedding ring. But not a single tear.

Thinking back over my life I realize that I have cried very few times out of grief. In fact, the only time I remember was after the funeral of my mother when I was fourteen years old. My crazy brother (no, he really was—in and out of mental hospitals all his adult life) had been very kind and comforting that day, no hysterical fits, no outlandish behavior intended to embarrass me in front of people). I said to him, “I love you,” and broke into tears. Maybe that wasn’t in grief as much as relief that he had stayed sane for an entire day.

Most of the times I cried were out of frustration and anger. People watching this thought I cried because I had my feelings hurt. That wasn’t it. I was mad and wanted to attack the bastard but I knew he was bigger than me. All he had to do is push me down and laugh at me because I wasn’t able to fight back. I could have hit him from behind but then people would think I was as crazy as my brother.

Certain movies had a way of making me tear up, mostly those with happy endings. The worst time was when my teen-aged son and I went to “Field of Dreams.” When the lead character’s father walked through the corn and they started playing catch, I broke down. I never played catch with my father. Of course I embarrassed my son. We had to sit there until the audience cleared out and I had composed myself.

I hated my job at a certain newspaper in the 1970s so much that I cried in the boss’s office. Once again I think it was frustration. Another time I cried when a prominent city’s community theater said it was seriously considering one of my plays. So that was out of happiness. I didn’t cry when they eventually returned it. I was used to rejection by that point.

Most of the time I have been able to choke back the tears. The trick is to keep my damn mouth shut. The less I talk the less likely I am to cry. As the years go by I have been more successful in controlling it, but mostly I’ve convinced myself I’ve experienced everything so emotions have become somewhat of a bore.

One time I choked up still confuses me. It was at the end of my college senior year. I went to the movies alone and ran into one of my former roommates. He was a loud flag-waving bigot. He was very specific about how every other race was inferior to white people, especially to white people of the United States. By the time I met up with him that last week in the movie theater, he seemed to have mellowed out on his political views or at least learned to keep them to himself. When we stood outside the theater after the movie we shook hands.

I was about to say, “Well, see you later,” when it struck me there wasn’t going to be a later. I hadn’t even given a second thought to all the people I had said good-bye to for the last time, but this choked me up. What the hell. I didn’t even like him.

I almost cried over this jerk, but I can’t even work up some tears for my wife of forty-four years. Maybe it’s because I know she’s still inside me and will never leave, so why cry over that?

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Forty-Seven

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Stanton holds the Lincolns captive under guard in the White House basement. Janitor Gabby Zook by accident must stay in the basement too. Guard Adam Christy tells the Lincoln Tad has become ill. Lincoln demands the boy be brought to them. Cook Phebe sees Adam take Tad in the room.

For an hour, Phebe kept an eye to her slightly ajar door, watching comings and goings of the white people. At times she could swear she heard a woman screaming something about my baby, my baby, and other times she thought she heard laughter. When Adam reappeared in the hall carrying Tad she felt an impulse to confront them again, but decided to stay prudently hidden. After they entered the service stairs, Phebe went to the next door and knocked.

“Neal?”

She heard a soft moan, followed by grumbling and padding of stocking feet across the room. Phebe stepped back when she saw Neal’s light coffee face speckled with nutmeg jut out the door and scowl.

“What do the white folk want now?” He paused before adding, “Tell them to get it for themselves. I’m off duty.”

“It ain’t the white folk.”

A smile, slightly soured by the hint of a smirk, crossed his lips.

“It’s about the white folks,” Phebe said in clarification.

“Oh.” The smile faded, replaced by a quizzical furrowing of his brow.

“Let me in.”

Opening the door wide, Neal stepped aside, absently buttoning the top of his woolen long underwear.

“I hope you don’t think this is anything improper, nothing romantic.” Phebe stepped inside, turned sharply, her eyes widening.

“I know.” Neal smiled and softened his gaze as he went to a small table to light a kerosene lamp.

“No,” Phebe said. “Don’t light the lamp.”

“Well,” Neal replied, “This room’s pretty black without light.”

“I don’t want anyone to know we’re talking.”

“Oh.”

“Shut the door.”

“We won’t be able to see each other.”

“Shut the door.”

He shrugged and closed the door, leaving them in complete darkness. “I feel foolish,” he said after a moment.

“I do too,” Phebe replied. “That’s why I don’t want you to see me.” She paused and added timidly, “And I don’t want to see the scorn in your eyes.”

“I never look at you with scorn.” A hurt tone clouded his voice.

“Yes, you have. But we don’t have time to fight over it.” She sucked in air. “There’s something strange going on.”

“Phebe…”

“And I don’t want to hear no scorn in your voice neither,” she said, interrupting him. “Please listen.”

“All right.”

Phebe closed her eyes to compose her thoughts. So many images raced through her mind that she had trouble deciding where to begin.

“The soldier boy—that Private Christy—carried Tad down here. They went into the billiards room. After a while they came back out, Private Christy looking around like he didn’t want to be seen.”

“So he didn’t see you?”

“Coming down they did,” Phebe said. “Tad said hello. The private turned red and looked away. On their way out, I just cracked the door.”

“What do you think it means?”

“If I tell you, you’ll laugh at me.”

“I’ve laughed at you before.”

“But those times you laughed because you thought I was funny. This time you’ll laugh because you think I’m crazy.”

“All right.” Neal paused. “No laughing at you. Tell me what you think is going on.”

“Well, I fixed the same meals for the Lincolns upstairs as I do for those important, secret people who stay locked away in the basement. Mr. Lincoln has peculiar eating habits, an apple and milk for lunch, just picking at a decent supper. Ever since September, when those mysterious important folks arrived, I never saw nobody go into that room.”

“Sure, a whole mess of folks go in there,” Neal said, “that soldier boy and Secretary Stanton.”

“You see? Don’t you think that’s queer, only two visitors, ever?”

“I don’t make it a practice to keep up with what the white folks do.”

“The lunch being sent downstairs now comes back with nothing eaten but the apple and milk.”

Neal remained silent. Phebe heard the cot creak as he sat. She had him interested, so she continued.

“About a month ago, the private came out of the billiards room with a laundry basket balanced on his hip as he tried to lock the door. Well, he lost his grip and dropped the basket.”

Neal snorted. “I always thought he was clumsy.”

“There was women’s underthings in the basket—I mean, all over the floor. I came out to help him pick everything up. When it dawned on me what I held in my hand, he snatched it from me and gave me this look like he wished I’d never seen those panties. But I did see them and that meant only one thing.”

“Which was?”

“There’s a woman in that room.”

“So?”

“So whoever heard of a woman advising men-folk about war?”

“Maybe she’s the wife of some diplomat,” he offered.

“No woman would stay in a locked basement room just to be with her husband, under her own free will, that is.”

“So who do you think the woman is?”

Phebe hesitated.

“Stop playing games with me.” Neal’s voice sounded impatient.

“If you don’t believe me, you’ll laugh. If you do believe me, you’ll get mad.”

Book Recommendation

Peg Woffington scandalized Ireland and England both on and off the stage in the 18th century. Lose yourself in Peg’s world of passion, fashion, royal intrigue and family turmoil. “Townsend was a wordsmith. The book held my interest. I was not familiar with the actress Peg Woffington until reading this book. Well written. Fascinating look into the life and times.” Amazon review