My eyes popped open in predawn darkness to the worst situation which could befall an elderly man in his bed. Somehow someone had left the windows unlocked, and curtains flapped in the stultifying breeze. Two to three men entered quietly, one hiding beside the chest of drawers, another behind a side table and possibly crouching beside the luggage which still sat in the middle of the floor after our trip to New York.

I saw men because women have enough sense to be asleep at four o’clock in the morning instead of breaking into a stranger’s house to watch them stare back at them hoping that they in actuality were a dream.

We had made it quite clear to everyone we knew that we kept no large money amounts of money hidden in a closet and we owned no valuable antiques. Both sets of our parents always bought cheap furniture and appliances so we were stuck with really cheap garbage in our house.

Several voices in my head were giving advice all at the same time which was very confusing and gives me a headache, taking the crisis to a whole different level. I nudged my wife to tell her there were hulking, menacing men lurking in the shadows of the bedroom.

“Shut the hell up before you wake up the dogs. Go to sleep, dammit!”

Another voice told me this was the same dream I’d been having all my life. All I had to do was pull the imaginary AK47 from beneath my bed and blow their brains out. I scoffed at the idea because those imaginary bullets would tear holes in my very real old furniture and I didn’t have the money to replace them. I didn’t even have money in my dreams.

Another voice told me to get up and turn on the light. Once I realized the hulking shapes were just shadows of furniture and luggage I would feel better and go right back to sleep. I hate this voice. It was always chirpy and thought it had so much common sense. For one thing, if I were having a bad dream then scientifically I could not move my legs to get out of bed to turn on the lights. During deep sleep all limbs are temporarily paralyzed to keep you from hurting yourself. Even if I did commandeer every ounce of willpower I had and was able to force my body into action I wouldn’t be able to get back to sleep. What good was ending the nightmare if I had to spend the rest of the night thinking about it?

The loudest voice was the craziest one of all, and I tried to ignore it as much as possible.

“Wouldn’t a nice tall cone of frozen custard taste good right now?” I told you. This voice was eccentricity personified. “We could just put our lips on the top of it and just barely suck on it and the frosty creaminess would fly down on our throats.” The frozen custard stand was open only a few months a year, and I was lucky to get one or two a season.

“I’ve got evil shadows in my bedroom!” I wanted to shout at this crazy voice but knew my vocal chords were frozen too, just like the delicious custard.

“The evil shadows in your room aren’t real. I’m not real either, but I’m much nicer to think about.”

By this time I had succumbed to the frozen custard fantasy and immersed myself into licking the frozen delight before it melted in the summer heat. Don’t let any drip on my shirt, or Mother will get mad at me. Oh hell, this is a dream, I don’t care if Mother gets mad at me or not.

Monthly Archives: December 2014

Burly Chapter Two

Late one night, early in December when the first blue norther was just about ready to sweep down on the East Texas prairie from the Panhandle, Burly Bear nudged little Herman who was fast asleep.

“Huh?” Herman mumbled.

“Not so loud,” Burly whispered, holding his burlap paw to his lips. “I want to talk to you, but if Callie or Tad wake up I won’t be able to talk.”

“All right,” Herman said as he yawned and rubbed his eyes. “What do you want to talk about?”

“Well,” Burly began slowly, looking down. “I’ve really enjoyed living with you and your family this year.”

Herman gave Burly a big hug. “And I love having you, too.”

“You love your mother and father very much, don’t you?” Burly asked softly.

Herman smiled broadly. “Oh yes. Mama is wonderful and papa isn’t half as scary as I thought he was. You helped me see that.”

“I can tell they love you too.” Burly paused for a long moment, then sighed deeply. “I want a family to love and to love me.”

“Why, Burly Bear,” Herman exclaimed. “I’m your family and I love you very much.”

“Shush,” Burly went.

Tad shuffled in his nearby bed. “Herman, shut up,” he mumbled, then rolled over and went back to sleep.

“I’m sorry,” Herman whispered.

“What I mean is, I want a family, a mama and a papa bear to love me and take care of me,” Burly finally blurted out.

“Herman wrinkled his little forehead. “I don’t know how we can do that. Usually parents come first, then the children.”

“But stuffed bears don’t usually talk. So usually doesn’t count here.”

“I guess,” Herman said in a dreamy sort of way, staring out of the window. He turned back to Burly. “Christmas is coming soon. I could ask for two more bears.”

Burly shook his head. “That really wouldn’t be fair, would it? I mean, you already have me, and Callie and Tad don’t have any bears at all.”

Herman’s eyes twinkled. “Oh yes. Callie would love a mama bear very much. She’s always telling me how cute you are. I’m sure she would like to have a bear just like you.”

“And Tad?”

Herman frowned again. “Oh, Tad. I don’t think he would like a stuffed toy. He’s almost grown.”

“Twelve years old is not as grown up as you think,” Burly said, adding wisely, “or as grown up as Tad thinks.”

“But Tad doesn’t like anything. I still don’t think he even likes me very much.”

Burly smiled. “I think he likes you more than you know. And he might like you better if he thought you liked him.”

“Oh, I like Tad,” Herman replied.

“But does he know that?” Burly asked. “What have you done to let him know?”

“I’m just six years old. What could I do to show Tad I like him?”

“You can do more than you think,” Burly replied. “Always remember that.”

“Okay.” Herman sighed. “What do I have to do?”

Burly whispered in Herman’s ear for several minutes, and then they both went to sleep, because they had busy days ahead of them before Christmas. After breakfast the next morning when the others left, Herman tugged on his mother’s apron as she washed the dishes.

“Mama, can I—can we give Callie and Tad something special for Christmas?”

His mother looked down at him with a sad look on her face. “I’m afraid none of us are going to get anything special this Christmas. You remember why, don’t you? I explained it all to you.”

Herman nodded seriously. “Yes. You called it the depressions.”

His mother laughed lightly and patted him on the head. “No, the Depression. Only one. Thank goodness.”

“But couldn’t you make Callie and Tad bears out of burlap, like you did Burly Bear?” Herman said quickly before all his courage went away.

“Why, yes, I suppose so.” She looked at Herman and looked proud of him. “I hadn’t thought of that. Yes, that would be a very good idea. You’re very smart, Herman. And sweet.”

She leaned over to kiss Herman on the cheek. One part of him wanted to pull away and pretend he didn’t like it. But another part liked it and wanted to hug his mother. That part won out, and Herman wrapped his arms around his mother’s waist. For a fleeting moment he noticed how terribly thin she was.

“If you want me to, I’ll go ask papa for the burlap,” Herman offered happily.

“You don’t mind doing that?”

“Oh no, papa and me, we’ve become big pals,” Herman bragged.

“Very well. He’s out in the barn, I think.”

Herman and Burly went out to the barn after putting on their coats, for the East Texas wind made the winter cold even colder than it was. Herman’s coat was made of denim, and Burly’s was actually a piece of old flannel with a hole in the middle. Papa called it a poncho. Moving bales of hay, papa had his denim coat off and his sleeves rolled halfway up his arms. Ever since he hugged his father for giving him Burly, Herman wasn’t afraid of those worms.

“Papa? May I talk to you a minute?” Herman spoke right up.

His father looked around, his face all twisted up from working so hard, but when he saw Herman he smiled very big. “Yes, son. What do you want?”

“I was thinking, it would be nice if Callie and Tad could have burlap bears like Burly for Christmas. Mother said she would make them if you had the burlap bags to spare.”

“That’s a good idea, son. I have a whole stack of empty ones over in the corner. You pick out two for your mother to make the bears.” He patted his son. “I was worried I wouldn’t have anything to give them this Christmas. Yep, you had a really good idea.”

Herman smiled broadly because both his mother and father had told him he was good for thinking of the bears for his sister and brother. He was beginning to understand what they meant when they said in church that it was more blessed to give than receive. All of a sudden, though, his happy thoughts turned to worry. In order for the new bears to be real parents to Burly Bear, they would have to be able to talk, just like Burly. And that would mean they would have to come from the same magical kind of burlap that Burly came from. What did Burly say about how he made his burlap bag move under father’s hand to make him think of making the stuffed bear? Oh, Herman wished father wasn’t standing so close so he could talk to Burly and get his advice.

Herman slowly touched all the empty burlap bags, but they all felt the same to him. He went through the stack again.

“Haven’t you picked out two bags yet?” his father yelled at him.

“No,” Herman replied. Maybe it was his father who had the magic touch to pick out the exactly right burlap to make the magical bears. “Would you pick the bags for me?”

His father walked over laughing. “You’re a good boy, Herman, but sometimes you do act silly.”

Herman was afraid his father wouldn’t take time to pick the right ones because at first he just grabbed the two on top.

“These will do,” he said, but then he stopped and looked at the bags. “Oh no. That won’t do at all. They got big holes in them. Let me look again.”

Herman smiled to himself. Father would make the right selection this time.

“Here, take these.” He tossed two bags at Herman.

It wasn’t long until Christmas came to the little farm house near Cumby. Father found a cedar tree, cut it down and dragged it into the house, filling the air with sweet evergreen aromas. Mother popped corn, and Callie and Tad strung the kernels together and hung them on the tree. Father bought a sack of cranberries which were strung on the tree too. All three children cut and colored paper ornament until the tree became pretty enough for the holidays.

Christmas Eve the family gathered around the tree after a meal of chili and cornbread. Father cleared his throat which was a sign for everyone to become still and silent.

“Times have been hard this year, and your mother and I can’t afford to give you anything except what we’ve always given you—our love. So I want each of you to come to your mother and me, and we’ll give you our present, a hug and kiss.”

Callie led the way and gave father and mother the biggest hug she had. Tad looked down and shuffled his feet like he was sad he wasn’t getting anything else, but he was able to give his parents a warm hug. Herman skipped over and got his hug and kiss, barely holding back a giggle, since he knew that wasn’t all some of them were getting.

After the children sat down again, father said, “Now two of you are getting something extra.”

“Yeah, and I can guess which two it’s going to be,” Tad grumbled.

“No, I bet you can’t guess,” his father said.

Mother pulled out the two bears wrapped in old newspaper. “These are for you and Callie.”

“Oh my goodness! Thank you! “ Callie yelled as she grabbed her package and tore it open.

“For me!” Tad squealed, his eyes dancing. He tore into his gift.

Each held up their burlap bears and hugged them, and then ran to their parents.

“They’re wonderful!” Callie exclaimed.

“Yes! Oh thank you!” Tad appeared younger and happier to Herman.

“You should tank your brother Herman,” their mother said. “He’s the one who suggested I make them for you.”

Callie hugged Herman and kissed him on the cheek. “Oh Herman, you’re so sweet!”

And so, Herman got his second Christmas present, the wonderful feeling of giving to someone else. Unfortunately, Tad broke the Christmas spell by throwing his bear to the floor.

“I don’t want the old thing!” he growled. “Herman just did it so he could get people to say he was wonderful. And—and he knew I wouldn’t want a silly old bear so he’d end up having two bears, the little pig!”

Callie turned red and stepped toward Tad. “Oh Tad!” She stopped abruptly, looked at her parents and sat down. For a nine-year-old girl, she was learning to mind her own business, Herman decided.

“Tad, that’s not a nice thing to say to your brother,” his mother said softly.

“Well, that’s what he is, a little pig!” Tad kicked the bear across the room.

“That’s enough of that, young man.” His father stood. “We’re going out behind the barn.”

After Tad and his father left, mother shook her head and sighed. “You other children go ahead to bed.”

Herman and Callie took their bears, climbed into the loft and got ready for bed.

“I really love my bear,” Callie whispered in the dark.

Herman had trouble holding back his tears. “Callie, honest, I didn’t suggest the bears to mama and papa just so they would say I’m wonderful. And I didn’t want a second bear for myself. Honest.”

“I know, Herman,” Callie said. “Good night.”

It sounded to Herman like Callie was about to cry. After a few minutes, when he was sure Callie wasn’t listening, he talked to Burly. “Why can’t Christmas be as nice as I wanted it to be?”

“The world isn’t perfect,” Herman replied. “Let’s just be happy for the things that do turn out right.”

“It was fun planning for the Christmas presents. And I liked getting a hug and kiss from Callie.”

“And I finally got my family,” Burly added.

“Yes, and I finally have my son,” a stranger girl bear voice said.

“Who’s that?” Herman whispered.

“It’s me, Pearly Bear.” The voice came from across the room behind the curtain.

“Mama, is that you?” Burly asked excitedly.

“Yes, Callie just dropped a tear on my head and all of a sudden I was talking.”

“How did you know your name was Pearly?” Herman was curious.

“That’s what Callie called me just before she went off to sleep. Son, don’t you think someone should go downstairs for your father?”

Burly looked up at Herman. “Uh yes. I don’t want papa to spend Christmas Eve on the cold floor all alone.”

So Herman sneaked to the edge of the loft so he could climb down the ladder to retrieve the other burlap bear when he heard papa and Tad come in the door. He pulled back so they wouldn’t see him.

“Why do you make me do things like this to you? Papa pleaded with his older son who just hung his head sullenly. “Do you think I want to whip you like that?”

Tad didn’t look up. “Maybe,” he mumbled.

“Well, I don’t.” Papa paced some and breathed deeply. “Don’t you know I love you best of all?”

Tad looked up, his eyes wide in surprise. Herman felt a pang of something sad in his chest and felt like crying.

Papa walked over to one of the straight back cane chairs and sat down. Herman could see he was bent over and on the verge of quivering all over, like he was very cold. Finally he looked up, and Herman saw papa had tears welling in his eyes.

“You’re my first born. You’re the first baby I ever held in my arms.“ He paused. “Look at yourself in the mirror. Don’t you see who you look like? You look like me.”

Again there was silence. Herman looked at Tad to see if he were about to speak, but he didn’t. He just shuffled his feet.

“I want the very best in the world for you. That means you have to be the very best you can be. And by God if I have to beat you ever day I’ll do it so you’ll be the best and have the best.”

They stared at each other a long time. Finally papa stood and walked straight to his room. Tad stood, staring at the bedroom door after papa shut it.

The silence was making Herman nervous. Ted turned and picked up papa bear and headed for the ladder. Herman scampered for his bed and pretended to be asleep. With his eyes squeezed shut, Herman waited for Tad to climb into the loft. He heard his brother’s steps as he moved across the rough floor. Suddenly Herman became aware that Tad was standing over him. Uh oh, Herman thought, maybe Tad heard him eavesdropping. Don’t let him get mad at me again tonight. Herman prayed desperately. But then he felt Tad’s hand gently touch his hair.

“Thank you for the bear, Herman.”

Herman didn’t move.

“I know you’re awake.”

Herman rolled over slowly and looked at his brother who cracked a small smile.

“He’s swell. I never had a bear before.

Herman was afraid to say anything, but that was all right because Tad turned and went to his bed. In a few minutes he was between the covers, and Herman couldn’t believe what he heard. Tad was crying.

In a few minutes, when all was silent again, a strange mature bear voice whispered, “Pearly? Burly Junior?”

Herman jumped. Burly jiggled a bit himself.

“Papa, is that you?” Burly asked.

“Of course.”

“I’m over here, dear,” Pearly whispered. “I’m so glad you’re with us. We’re a family at last.”

Burly put his burlap arms on Herman and squeezed. “Thank you Herman. Thank you for the most wonderful Christmas present of all.”

“Yes,” Pearly added, “thank you for my family.”

“I’m so happy to have my son,” Burly Senior said. “And he looks just like me!”

Herman looked sad. “Yes, I suppose even if you had other bear children, Burly would still be your favorite.”

“Of course,” Burly Senior replied. “Just as your first child will always be your favorite. But that doesn’t mean I won’t love the others very much. And you will love your other children very much.”

“Don’t be jealous, Herman,” Pearly said. “Your father loves you very much.”

‘I already told him that,” Burly said.

“And you’re right. Always listen to Burly, Herman,” Pearly added.

Herman forgot the pang in his heart, smiled and hugged Burly tight.

“Merry Christmas, Burly.”

Which Tree?

Three fir trees on the edge of the forest were chatting one morning in early December.

A huge fellow, about twenty feet tall and wide at the base, ruffled his limbs. “I don’t know what you two guys are planning for Christmas but I expect to be center of attention downtown this year. Oh yeah, on the square overseeing the Christmas parade. Anybody who is anybody will be there with their kids watching the parade pass in front of me. I’ll be lit to the max with lights and a star on top.”

“That’s nothing,” a ten footer with lush green boughs replied. “I mean, if you go for that common man scene where they let absolutely everyone near you, I suppose that’s okay. As for myself, I’m selective about my company. Not saying I’m better than anyone else, but let’s just say I have discerning taste. I’m winding up in the grand foyer of a millionaire’s mansion, decorated with only the most expensive ornaments and lights. I’m talking Waterford crystal here, and I’ve got the branches to hold them.”

The third tree, not more than three feet tall and with scrawny limbs, just stood there without much to say.

“What about you, junior? What do you expect to be doing on Christmas morning? Brunching with the chipmunks?” The middle-sized tree blurted forth a forced ha-ha-ha. A nice baritone but shallow as could be.

“Now, now,” the largest tree chided. “We shouldn’t make fun of our inferiors. We all can’t be the best, most important Christmas trees in town. Not even second best, like you who will be charming to a small group but not as the official town tree.”

The littlest tree felt like he was about to ooze sap out of sadness but knew it wouldn’t do any good. The other trees were right. Who would want him except for kindling for the fire. He wasn’t big enough to make a decent Yule log.

Just at that time a caravan of cars leading a large tractor-trailer truck pulled up in front of the three trees. A group of important-looking dignitaries crawled from their cars and circled the largest tree as the crew pulled its equipment from the truck.

“Oh, yes, I think this one will do fine,” a large bald man announced as though he was thoroughly practiced at making important decisions.

“Oh yes, Mr. Mayor, this one will be more than fine.” The others standing next to him quickly agreed with him.

The crew started its chain saw, chopped the fir down and laid it on the flatbed truck.

“See you never, suckers!” the biggest tree called as the municipal procession disappeared.

“Commoner!” the middle-sized tree replied.

A couple of hours passed before a long limousine with shaded windows rolled up to the two remaining firs. A chauffeur jumped from the driver’s seat and opened the door for a couple elegantly dressed in fur and leather. The woman, with her artificially colored blonde hair piled on her head, sipped from a champagne glass, while the man fixated on his cell phone.

“Oh, Maxim,” the woman cooed. “You did a wonderful job scouting out the most beautiful tree in the forest.” She ran her fingers across the chauffeur’s broad shoulders. “Of course, you do everything well.” She turned to the man on the phone. “So, what do you think Joey? Is it big enough for our grand staircase?”

“Yeah. Sure. Whatever.” The man didn’t look up from his phone. “Max, cut it down.”

The chauffeur cut down the middle-sized tree, carefully tied it to the top of the limousine and they got into the car to drive away.

“Good luck, shrimp! You’ll need it!” the tree called out as the car disappeared around the bend.

At the end of the day, the sky darkened, and a small old car rambled up to the small tree and stopped. Three small children poured out of the back seat and ran to the little tree.

“Oh, daddy, this one will be perfect!” they sang as a chorus.

“That’s good,” a young man in ragged overalls said. “Anything bigger wouldn’t have fit in the car.”

A wispy haired young woman came around the car. “Stand back, children. I don’t want you close when your daddy starts using that axe.”

“Oh, Mommy, you worry too much,” one of the children said with a laugh.

On Christmas Eve, everyone in town gathered on the square to watch the Christmas parade and ooh and ah over the beautiful lit giant tree. Floats rolled by, and the people on them pointed and shouted at the town’s big Christmas tree. Bands with drummers, tubas and more marched past. Each one made the tree feel prouder and prouder.

On Christmas Eve night, elegantly dressed couples gathered in the millionaire’s mansion and oohed and ahed over the beautifully decorated tree by the grand staircase. They all drank champagne and nibbled on appetizers served on a silver tray by Maxim who also turned out to be the butler. The ladies in their lovely gowns asked the millionaire’s wife when they were leaving for their estate in the Bahamas.

“Midnight,” she replied. “We always spend Christmas day in the Bahamas. It’s our family tradition.”

Also on Christmas Eve night, across town in a small wooden house, the family decorated the little tree which they placed on a table in the corner of the living room. The room smelled delicious from the freshly popped corn which they strung and hung on the tree. The children kept busy coloring, cutting and hanging the new ornaments on the little tree. The room was alive with the constant giggling of the children, and the little tree decided this wasn’t a bad place to be.

The next morning, everyone in town was home, opening presents and enjoying Christmas dinner with family and friends. The large tree downtown had already been forgotten. It kept hoping to hear another oom pa pa coming down the street but it didn’t. The enormous fir shivered first from the cold wind and then from the loneliness. It couldn’t decide which was worse.

In the millionaire’s mansion, everything was dark and still. No more elegantly dressed people wishing each other season’s greetings, just a numbing silence. The middle-sized tree decided all that Waterford crystal was making its branches droop. Not even Maxim was there.

Meanwhile, in the small house across town, the family gathered around the tree to open presents. The children tore away wrapping paper to see new socks and underwear and hugged their parents gratefully for it. Then they cooked their modest Christmas feast and settled back around the tree with their plates in their laps and ate every bite of it.

Now you tell me. Which was the grandest Christmas tree of all?

About Burly

Starting today, I will post a chapter each Friday of my juvenile novel Burly.

Burly is a teddy bear made of burlap who belongs to Herman, a little boy living with his family on a North Texas farm during the Depression. He is Herman’s friend, confidante and confessor because, through some magical transformation, Burly can talk. It’s a bit like Winnie the Pooh plunked down in the middle of Grapes of Wrath. I was told once that it wasn’t historically accurate because children in the 1930s didn’t tell each other to shut up, I hate you and fight. Too young to have experience life back then, I declined to disagree, but I have a feeling she had a selective memory. So this may not be a story to ready to very young children, but older children might appreciate it.

Burly, Chapter One

Chapter One

Tiny rivers of rain rolled down the misty window pane by Herman’s bed in the loft of his parents’ farmhouse. They lived fifteen miles south of Cumby in North Texas, basically in the middle of nowhere. He didn’t know what time it was. All the thin sandy-haired boy knew was that it was wet, cold and dark, and the he was lonely.

Now it was odd that he would feel lonely. His brother Tad lay in a bed not three feet from him and across the room behind a curtain held up with clothes line was his sister Callie. Downstairs in the room behind the kitchen were his parents. But still, Herman felt very lonely and very, very sad. Why should he feel this way? He didn’t know why; after all, he was only five years old. Soon the sad and lonely feelings became too strong, and little Herman began to cry softly until he finally fell asleep.

The next morning, after Callie and Tad had gone to school, Herman summoned his courage to talk to his mother about how he felt so lonely late at night, when everyone else was fast asleep. He didn’t dare mention it while he, his brother and sister ate breakfast. Tad, he knew, would have made fun of him.

“Mama,” he began hesitantly. “Do—do you ever feel sad and lonely—like at night?”

His mother stopped washing the dishes and looked quizzically at Herman with her soft gray-blue eyes. She brushed a wisp of light brown hair from her face and asked, “Whatever makes you say a thing like that?”

Herman shifted nervously in his home-made cane-bottomed chair and looked around the big room, first at the pot-bellied stove and then at the worn couch and chair in the far corner.

“Oh, it’s just that, late at night, when I can’t get to sleep, I start thinking that I’d like to have a friend.”

“Why, you have plenty of friends,” she replied with soft laughter. “There’s me, I’m your friend. And your papa. And Callie thinks you’re adorable. And your brother Tad–”

“I don’t think Tad likes me very much,” Herman interrupted.

“Oh, he’s your friend,” his mother reassured him. “It’s just he’s going through that age when I don’t think he likes anyone much.”

Herman almost added he didn’t think his papa liked him much either, but he didn’t because that really wasn’t what he was talking about.

“I mean, I want a friend my own age.”

His mother threw back her fragile head and giggled. “Well, there’s not much I can do about that. Living on a farm out here in the country like we do, we don’t have many youngsters running around for you to play with.”

“But still…” Herman’s voice trailed off. He knew his mother was right, and there wasn’t much use in talking about it anymore.

After a moment of silence that seemed as sad and lonely as the rain on the window pane, Herman’s mother said quietly, “You go one and gather the eggs in the hen house.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

He walked slowly through the front door and around the side of the weathered wood-frame house to hen house next to the barn. He stopped short when he saw his father unloading sacks of grain from their old pick-up. His father never beat him nor had he ever said a harsh word to him. But Herman was still a little afraid of him.

Father was a tall, boney man who looked like he had long worms all over his arms. Mother tried to explain to him once that those were just papa’s blood vessels. They stuck out like that because papa wasn’t very fat, but he was very, very strong. Still, Herman thought they looked scary. Maybe they would seem scary if his father ever hugged him, but he didn’t, so the fear still pestered Herman like a mosquito on a hot summer day.

“Hi, papa!” Herman yelled out, trying to be friendly. His father looked at him, grunted and went about his work. So Herman went about his own chores. He did have to admit he felt good about helping out. He brought in the eggs, kept the kindly box next to the pot-bellied stove filled and helped his mother set the table every evening. He went into the dark hen house and felt into the warm, downy nests to find eggs.

Soon he became aware of voices outside by the barn. It was mother and father talking. Herman knew it wasn’t very nice to eavesdrop, but he put his head to a crack in the hen house to listen anyway.

“Woody,” his mother said warmly but with just a touch of urgent pleading, “it would mean so much to the boy if we could give him a teddy bear for his birthday. It’s next week, you.”

“Now you know we can’t afford any fancy extras like toys,” his father replied wearily.

“Just this morning he was telling me how he wished he had a friend,” she continued. “A teddy bear, just a little stuffed something for him to hold onto at night so he won’t be afraid.”

Herman’s heart jumped a moment. A stuffed animal to hug at night. It was too good to be true.

“Opal, we just can’t afford it,” his father said in his voice that meant he was tired of talking.

Just then something odd happened. Peeking through the crack Herman could see his father looking down at the burlap bag underneath his hand. His father stroked it and patted it for a second then looked at his wife. She stepped closer to him, and they talked in low tones, so soft that Herman couldn’t hear them anymore so he went back to gathering eggs.

Herman didn’t think much about what his parents had talked about that day. The next weeks he was too busy gathering eggs and kindling and playing with rocks which he pretended were cars and trucks. He sang songs with his sister Callie and had a fight with his brother Tad, for which his mother gave them both spankings.

One night after supper, mother cleared away the dishes and brought out a small chocolate cake—Herman’s favorite—with six flickering candles on it. She and Callie sang happy birthday while his father and Tad sat there and pretended to mumble the song. Herman had actually forgotten his birthday. But when he blew out the candles and tasted the sweet chocolate cake he remembered—only for a second—what his mother had said about a teddy bear. After everyone had finished the cake, his mother with a beaming smile on her face pulled out a bundle wrapped in butcher’s paper.

“I colored pictures on the wrapping paper,” Callie announced proudly.

For a nine-year-old girl with too many freckles she was very nice, Herman thought.

“What! He gets a present!” Tad exploded.

“Be quiet, son,” his father said softly but firmly.

“But he don’t do half the work around here that I do, and he don’t have to go to school!”

“Oh, shut up, Tad,” Called chided her brother.

“You shut up,” he retorted.

Tad was a big twelve-year-old but he looked like a pouting baby when he was angry, which was too often, Herman believed.

“Now both of you, settle down before I take you out behind the barn,” their father warned.

“But it isn’t fair,” Tad whined.

“Shush,” his mother added, handing the gift to Herman.

“Not fair,” Tad said under his breath.

Herman was sad his brother was made, but he put that out of his mind as he tore into the paper and what he found made him grin from ear to ear.

It was a bear made of burlap with buttons sewed on his arms and legs so that they could move. He had a sweet little smile sewn on his face. Two more buttons made the eyes.

“Ooh, how pretty!” Callie cooed, hugging Herman. “Isn’t it wonderful, Herman?”

Herman was speechless.

“Mama made it,” Callie told him.

“It was your father’s idea to use the burlap bag,” their mother said, smiling sweetly and nodding to her husband.

Herman jumped up, without thinking about the worms on his father’s arms, and ran over to hug him and kiss his rough, weather-beaten cheek. For the first time he could ever remember, he felt those long, strong arms fold gently around him and pat him softly. He his stood quickly.

“Um, I’ve got to go see how the livestock’s doing,” he mumbled, rubbing his eyes with his hands and walking with long strides out the door.

Mother looked at the door long after father went through it and then rubbed her eyes gently with her hands. “Time to clean up,” she announced crisply. “Callie, clear away the dishes.”

“Mama, can I play with my bear?” Herman asked timidly.

“Of course, dear.”

“What are you going to name him, Herman?” Callie said excitedly, leaning down to look at the bear.

“I don’t know,” he replied simply.

“Why don’t you name it after yourself,” Tad said with a nasty sound in his voice. “Baby.”

“Oh, shut up,” Callie spat, then turned back to Herman. “Since he’s made out of burlap, why don’t you call him Burly?”

Herman smiled. “Yeah. Burly Bear.”

“Mama,” Tad began to complain, “it ain’t fair Herman gets fancy toys and I—“

“It isn’t a fancy toy,” his mother interrupted sharply. She sighed deeply, then smiled wearily. “And whether it’s fair or not—well, I’m just too tired to worry about it. Times are might hard, children. Things aren’t fair for just about everyone. Maybe Mr. Roosevelt can do something about it but for now, let’s just try to get along and surive.”

Herman turned for the loft ladder when Tad jumped in front of him, pointed his finger and made a silly face. “Baby, baby, baby,” he said in a mean sing-song voice.

Called ran over and kicked Tad in the sins and screamed, “You’re so dumb and awful! I hate you!”

Tad yanked Callie’s long, stringy hair. “Oh stay out of this!”

Tad and Callie began to fight and scream but stopped very fast when their father came throught he door and bellowed, “Hey! What’s goin’ on here?”

Both of them tried to tell their side of the story but since they were talking at the same time their father couldn’t understand either one. “All right,” he announced, “I’ve had enough of this. You’re both going out behind the barn.”

With muffled protests Callie and Tad went out the door with their father. Herman was glad he kept his mouth shut because he knew what awaited them behind the barn, a paddling.

“Why does Tad always call me a baby?” Herman asked his mother.

She smiled and slightly and hugged him. “Why, you are the baby of the family. And you’ll always be my baby, even when you’re grown and as big as papa.”

“Gosh, will I be that big?”

“Yes. Now get ready for bed. Take Burly with you.”

Herman climbed into the loft, took his clothes off and got into bed with Burly. He looked out of the window at the dark sky and thought how lonely he still felt. Burly was wonderful, and he could him hug him; but, Herman still felt lonely and sad. Part of it was because Tad made such a fuss and another was—well, Herman still didn’t know why. Again, as so many nights, tears began to fall from Herman’s eyes.

“Herman,” Burly said in a soft, soothing voice, “please don’t cry.”

Herman looked around. He didn’t know where the voice came from. Then he looked down to see Burly smiling up at him.

“Burly! You’re alive! You can talk!”

“Not so loud,” Burly shushed him. “Yes, I can talk, but only when it’s just you and me. When Callie and Tad, or anyone else is around I’m just a regular stuffed animal.”

“But why?”

Burly wrinkled his brow. “I don’t know. I don’t know why I can talk. But when your tear hit the top of my head I began to talk. That’s all I know.”

“Oh this is wonderful,” Herman whispered, hugging Burly tightly. “Oh! I didn’t hurt you by squeezing too right, did I?”

“Oh no,” Burly replied. “We burlap bears are pretty tough.”

“And you’ll be my friend!”

“Of course, I’ll be your friend,” Burly said. “I’ve been your friend ever since I was that feed bag. Remember, you rode in the pick-up to buy me at the feed store.”

“Not really,” Herman had to admit.

“You impressed me because you were so nice and kind and polite,” Burly explained. “And honest.”

“Thank you.”

“See how polite you are. Do you want to know a secret? I t was really my idea for me to be made into a bear. I made the bag rustle underneath your father’s hand that day so he would notice me and get the idea.”

“I didn’t think papa liked me enough to think of it on his own,” Herman sighed, a bit sad.

“Oh no, Herman,” Burly corrected him firmly. “Your father loves you very much. I could have sat there rustling all day long, but if he hadn’t really wanted you to have a bear, my rustling wouldn’t have meant much.”

“Oh.” Herman was happier knowing his father did love him after all.

“And do you know why he left so quickly after the birthday party?”

“He had to check the horses and cows,” Herman replied innocently.

“Wrong again,” Burly said. “He left because he didn’t want you to see him crying.”

“You mean papa cries? Gosh, I didn’t think anybody that big and strong ever cried.”

“Your father cries all the time, but you and your brother and sister don’t know it. He loves you all very much, and it makes him said when he can’t give you more things.”

“I guess things don’t matter as long as I know papa loves me.”

“Oh my, nice and kind and polite and smart too,” Burly sang. “I knew I was right to want to belong to you.”

Herman smiled a little, then thought of Tad and sighed. “I just wish Tad didn’t hate me.”

“Your brother doesn’t hate you,” Burly said. “He’s just jealous because he never got a stuffed bear. And he’s jealous because he has to go to school and help on the farm more than you do.”

“I do what I can,” Herman protested. “I’m only five.”

“Six. But you see, Tad is still just a little boy, even though he is bigger than you, so he doesn’t understand these things.”

“So maybe when he’s older he won’t hate me,” Herman said hopefully.

“Of course,” Burly assured him. “After all, he is your brother.”

Herman smiled and hugged Burly, knowing he would never feel sad or lonely again. “And you are my friend.”

“Yes, and you are my friend.”

Herman heard Callie and Tad come into the house, muttering and crying. He felt sorry they had gotten into trouble but felt good that they would know better as they got older. Like he would know better as he got older, with the help of Burly Bear, of course. He hugged Burly once more.

“Happy birthday, Burly.”

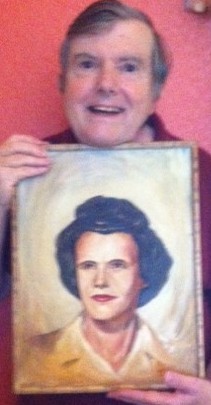

Golden Aura of Art

Art is not only in the eye of the beholder; it is also in the heart of the beholder.

My mother died when I was fourteen, and two years later I had a job as part-time janitor at the Baptist Church. It didn’t pay much, maybe 75 cents an hour but it was just 1963 so what could I expect. At Christmas I wanted to give my father something special. After all, before then the only gift I could afford was a cigarette lighter.

And it’s not like I felt I owed him for a great present from the year before. In fact, the first year after my mother died, my father came to me with his wallet open and asked, “What’s the least amount of money I can give you for Christmas to make you happy?”

“Oh, 10 dollars, I guess.”

He had an odd expression. I didn’t know if he thought I had asked for too much or I had just let him off the hook. I don’t even remember what I bought with the 10 bucks. This year, though, I wanted to give him something nice just because he was my father.

In his bedroom was a black and white photograph of my mother when she was in her late thirties. I took it out of the frame to take it to an artist. My father wasn’t very observant so he didn’t miss it. Someone recommended this guy who had a place in downtown. I walked in, and there I was surrounded by mats and barbells and paintings. It seemed he ran a combination karate school/art studio.

“How much do you have?” He was trying to sound tough.

“How about 50 dollars?”

“Make it 75.”

I said okay because I didn’t want to get beat up. On Christmas Eve I went by the karate school/art studio to pick up the painting. He had taken a simple black and white photograph and gave it a golden aura. When I brought it into the house that night I was intercepted by my brother who demanded to know what I was up to.

“It’s Dad’s Christmas present.”

“Are you stupid? He’s got a girlfriend now. He doesn’t want to be reminded of his dead wife!”

He was six years older than me, so I figured I must be wrong. I took down a picture on the living room wall and hung the painting there, hoping my father wouldn’t notice it on his way out the door on a date. A couple of weeks later, I heard my father call out my name. He was standing in the living room staring at the painting.

“Where did this come from?”

“I had someone paint it from the photograph of mother.”

He paused to look closely at it.

“Okay.”

That was the last comment ever made about the painting except for one aunt who was visiting one day and saw it.

“It’s pretty good, except the hair color. Her hair was a lighter brown. That ruins it.”

The painting stayed in the living room for thirty years until my father died and then I brought it to my house. It’s in my bedroom over the desk where I write. Every now and again I stop what I’m writing and think of that Christmas 50 years ago. I don’t know if my father ever realized it was supposed to be his present from me. My brother never apologized for denying that special moment on Christmas Day when I would have presented it to my father.

“Well, he could have gotten mad about it.” That’s the only excuse he could come up with.

Everyone in my family is dead except me, but I still have that golden aura vision of my mother and that is enough. It’s art in my eyes and in my heart.

Christmas Spider

On Christmas Eve Mother Spider paused a moment after delivering her babies, looked through the branches of the small fir tree to watch the sun set over the Austrian snow drifts and sensed she would not live to see Christmas morning. She did not mind so much—for spiders only had a brief span on this earth—but she wanted to leave her darling little children a special memory of their mother before she went away.

A heavy thud interrupted her thoughts. Running to the tip of the branch she saw a woman, wrapped in rags, chopping away. Mother Spider had heard legends of humans putting evergreen trees in their houses on Christmas Eve, hoping that an angel—one of those who heralded the birth of the Christ Child centuries ago—would visit every home. The tree which symbolized best of love and peace merited the granting of the family’s wish for the New Year, whatever that wish might be.

Mother Spider consoled her children who became frightened by the jostling and thumping as the woman dragged the tree from the forest into her small cottage. Two little girls and a boy ran to the door and with giggles galore helped their mama set the tree in the corner by the fireplace.

“My dears ,” the woman told them, “we will not be decorating the tree this year because I did not have time to gather nuts and holly and we have no fruit to adorn the branches.”

“Don’t worry, Mother,” the older girl replied soothingly as she patted her mother’s shoulders. “We remember how pretty the tree looked before father died. That is enough.”

“We’ll decorate the tree with our Christmas memories,” the boy joined in. “It shall be the prettiest tree we have ever seen.”

The woman put her face in her hands and cried.

“Don’t cry, Mother,” the other girl cooed. “It’s Christmas. We are together. What more shall we want?”

“You don’t understand, children.” She wiped her face with a cloth. “If we cannot pay the landlord at the first of the month, we will be cast out in the snow.”

“We always have the Christmas angel.” The boy hugged her. “Surely she will see this is the best tree in all the kingdom and grant our wish.”

After kissing and hugging each of her children, the woman gave each of them a bowl of porridge for their supper. Then the family settled on an old feather mattress, snuggling under worn quilts, and fell asleep.

Even as she felt the life slowly slip from her body, Mother Spider decided she would decorate the family’s tree with the last of her web. She told her little spiders what she was doing and that they should stay nestled among the branches for they had had a long, busy day and needed their rest. When she was sure they were all in a deep slumber, Mother Spider began her task, beginning at the bottom of the tree and working her way to the top, spreading her silvery fragile tinsel.

At first she did not think she had the strength to finish her job, but she paused to consider the poor woman and her three loving children who needed the angel to grant their Christmas wish. When she finally reached the top of the fir tree, Mother Spider turned because she thought she heard the flapping of gossamer wings.

There before her was the Christmas Angel, emanating her soft heavenly light. The spider breathed deeply, trying to stay alive for a few moments more. The angel glided to the tree.

“My dear little spider,” the angel whispered in a loving lilt. “What have you done?” She smiled. “You don’t have to speak. I can read your heart. Rest, tender spider, for your labor has won your wish for this desperate family. Behold, your web is now silver spangles and when you depart your body, I shall make your body into a brooch of rubies and diamonds.”

Mother Spider looked down to see her baby spiders scampering across the branches.

“Your children are here to say their farewell. Go now. What a gift you have given them.”

The next morning the woman and her daughters and son awoke to the sun coming through the window, making the silver tinsel shine. They danced and sang around the tree. Then the mother noticed the ornament at the top and screamed for joy when she saw the rubies and diamonds. The family never wanted for anything again, and shared its good fortune with the destitute of the village.

In the years to come, the spiders who witnessed their mother’s transformation into the grandest Christmas gift ever, told their children who in turn told their children of the miracle they witnessed. Each one wished that one wintry night they would be fortunate enough to live in a fir tree chosen to be blessed by the Christmas Angel.

(Author’note: This is a new interpretation of the Christmas spider legend.)

The Toymaker

“Papa, will you ever forgive God for letting mama die?”

The toymaker did not lift his gray head but continued to sand on the nutcracker.

‘Papa, it isn’t fair to me. When you hate God, you don’t have time to love me.” Gretchen extended her tiny, pale hand to her father’s tattered sleeve.

“Leave me alone.” He pulled away. “If these toys are not finished by Christmas, the duke will not pay me, and then what will we do?”

Augustave’s wife Henrietta died while he was away in the king’s navy. A new attack from the Swedes delayed his return, leaving his wife and daughter on the brink of starvation. Henrietta went to Menchlaus’ tavern to beg for food. Menchlaus demanded too high a price so she walked away with her honor intact, but still no food for Gretchen. On the day of Augustave’s return, Henrietta died, her body draped over her daughter to protect her from the cold. Gretchen lived but her father faced a decision, go back to the sea to the life he lived or remain home to raise his daughter. With resignation Augustave bade farewell to the navy and opened a toyshop in his parlor. He had a talent for carving, but no love for it.

Gretchen smiled. “Yes, the duke loves your toys. All the children of our village love your toys. What child would not want a wooden horse waiting for them on Christmas morning?”

“Will you please stop your incessant babbling? You will cause me to cut myself, and I won’t be able to finish the nutcrackers? Where will we be then, eh?”

Gretchen walked away to the kitchen where she began to make cookies. Soon the house was filled with the aromas of ginger and cinnamon. After the cookies came out of the oven, she let them cool and covered them in icing. Placing them on a platter, Gretchen went to the front door and opened it.

“Shut that door!” her father yelled. “It’s the dead of winter!”

Saying not a word, Gretchen stepped out into the night air and disappeared. Finally the last nutcracker was finished and ready to present to the duke on Christmas Eve. Augustave looked around for Gretchen, but she was not there. Then he remembered. Gretchen walked out the door with a platter of cookies. He ran to the door and flung it open.

“Gretchen! Where are you?”

She was nowhere to be seen. Augustave followed the footprints in the snow as well as he could. Every once in a while he saw one of the cookies on the ground. They led to the church at the end of the lane. Inside the door was Gretchen, sitting patiently for him to arrive.

“Thank God you are safe!” He grabbed her up in his arms. “I don’t know what I would have done if I had lost you!”

“Does this mean you forgive God now?” she whispered in his ear.

(Author’s note: this is an adaptation of an old folk story The Red Sail.)

My Lips Are Sealed

Dammit, I had to pick up my brother Royce at Love Field again. He would be drunk and would slur insults all the way from Dallas to our home in Gainesville, an hour’s drive away.

One thing I liked about my father was that he had confidence in me not to get in any trouble. One thing I didn’t like about my father was that he made me go to the airport when my brother was flying in on leave from the Marines. I was eighteen, and today that would be considered child abuse but in 1966 it was okay.

Experience told me to skip going to the gate. Go straight to the main concourse bar, and there he was, sitting at the bar bending some guy’s ear.

“…and that’s why you should never eat breakfast.”

As soon as I walked up, the guy mumbled something about Royce’s ride being here, threw some bills at the bartender and got the hell away from my brother as fast as he could. In a few minutes we were driving on Mockingbird Lane toward the interstate when my brother ordered me to take a left at the next block.”

“What?”

“Just do it! Dammit!”

One thing I learned about driving with a drunk in the car. Go ahead and do what they say. A lot less hell to pay. Next he pointed to an apartment complex on the right and demanded I pull in there. After I stopped the car and turned off the engine, I guessed that Royce had progressed from mere alcohol to marijuana, and this is where his dealer lived.

“Go ahead and thank me. I’m going to get you laid.”

“What?”

“Just get out of the car! Dammit!”

So we got out of the car, and Royce staggered toward an apartment and banged on the door.

“Candy! I got some business for ya!”

“Is that you, Royce?” a woman with a husky Texan drawl called out. “Haven’t I told you time and time again I don’t do that shit anymore? I’m gonna be an actress, so go to hell!”

“It’s not for me, Candy. It’s my baby brother.”

“No! Go away!”

Royce repeated the name Candy loudly in a sing-song voice until the door opened, and a dirty blonde in capri pants and a loose man’s shirt grabbed my brother’s arm and pulled him in.

“Shut up for God’s sake!” she hissed. “The neighbors will call the cops!” Then she looked at me. “You too, little boy. Are you really this drunk’s brother?”

“Yes, ma’am,” I replied softly as I entered the apartment. It wasn’t as run-down as I thought. Actually, it was rather expensive looking.

“I want him to lose it tonight,” Royce announced, pointing at me. “And you’re the girl to do it.”

“Royce,” Candy said with a sigh and shaking her head, “you have pulled some stupid shit before but this is absolutely crazy.”

He ignored her, fumbled with his wallet, pulling five twenty dollar bills and shoving them into my hand. “Now don’t you dare give her the money until you got what you came here for.”

“You’re not going to watch, are you? I mean, you’re not going to tell me where to put my elbows and things like that?”

“Dammit, kid. You don’t know what I’m doin’ here. This bitch is Candy Barr! The best whore in Dallas!”

“I told you, Royce, I don’t do johns anymore! I’m a dancer!”

“Then why did you lay me?” he shot back.

Candy smiled slightly. “Because you looked so pitiful when you came into the Colony Club that night. You didn’t even know what kind of drink to order.”

“Well, he’s more pitiful than I was, so get in that bedroom! I want to get home and get some sleep!”

Candy motioned at me, and I followed her into the bedroom.

“First thing, go into the bathroom, take off your clothes, take a hot, soapy shower, and when you come out I’ll be in bed.”

“I took a bath before I drove down here,” I replied weakly.

“Dammit, do what she says, kid!”

Royce must have had his ear crammed next to the door.

“I’m so nervous I don’t think I can turn the shower knob on. Could you show me?”

Candy was smarter than she looked because she cocked her head, as though she knew what I was thinking.

“Sure, little boy. This way.”

After we entered the bathroom I turned the shower on and closed the door so Royce couldn’t hear us.

“So you’re the Candy Barr, Jack Ruby’s girlfriend?”

“Well, let’s just say friend. Jack’s not exactly boyfriend material.”

I couldn’t help but smile. “So you know a lot about who killed Kennedy?”

“You don’t want to know, little boy.”

“Yes, I do. Listen, I’m not going to go to bed with you. You seem like a nice lady, but, no offense, you’re really too old for me.”

“Thank God, somebody in Royce’s family has some sense.”

“So we’ll go back into the bedroom, bounce on the mattress while you whisper stuff about the assassination in my ear. Then I give you the hundred bucks, and Royce will get off my back, okay?”

She nodded and turned off the water. As we walked back into the bedroom she whispered, “Your brother likes a lot of noise, you know what I mean?”

“Oh, you’re really hot!” I screamed as we sat on the bed and started bouncing.

“Thatta boy, kid!” Royce yelled on the door, banging it with his open palm.

“Oh, yes, yes, yes,” Candy purred as she leaned in and began murmuring all the good dirt on what happened that day three years ago.

“Wow!” That was actually in response to what she told me, but it also pleased Royce to no end.

“That’s it! That’s it!”

I had some theories of my own about who shot President Kennedy, but I would have never guessed the truth.

“What’s goin’ on in there? I don’t hear any action!”

“Now! Now! Now!” Candy was in hysterics. I decided she would be a good actress.

My mind went blank, so I had to improvise.

“Oh, come all ye faithful!” I sang. It was all I could think of.

“Yes! Yes! Yes!” Royce was enjoying this way too much.

While I put my clothes back on, Candy muttered one last thing in my ear. “By the way, little boy, you can’t ever tell anyone this, because some big thug will come in the middle of the night and blow your head off.” She put her hands on my face and smiled. “And it’s such a sweet little head, too.” Then she kissed my forehead.

I handed her the hundred dollars and opened the door. Royce hugged me, unintelligibly congratulating me on my transition into manhood.

“Was it great?”

“Words can’t describe it.”

Grateful for Families

One of the things that I have enjoyed the most in the last few years has been observing the American family. Despite what some may think, it is truly magnificent.

In May and October I tell stories at a local farm which creates five-acre mazes. All the generations come out to play. It’s just walking along paths through cornstalks or giant sunflowers, but everyone has a good time. Grandparents end up sitting under giant oak trees watching the little kids ride ponies and pet chickens, cows and goats. Parents have fun too but use the activities to teach their children to behave and play fair. The family which runs the attraction has grandparents supervising the entrance to the maze and making lemonade. The children help with the toting and selling bottled water.

I participate with a theatre group which involves all the generations. One woman talks about her “baby” going off to college. He’s six-foot tall, has a beard and plays the romantic leads in plays, but he’s still her “baby”, and I suspect he doesn’t mind at all. Other theater families cheer on their youngsters theatre ambitions, keep them humble when they have leading roles and encourage them to be the best chorus singer or scene changer they can be.

Another guy I know is at every baseball and football game his son plays in, and he lets everyone know how they went. Still another man planned an elaborate ceremony for his son’s eighteen birthday and encouraged his son to ask him anything he wanted to know about being an adult. No holds barred, no topic too sensitive.

I have seen the same families go through trials of illness and disappointments with the same unconditional love and support. When the troubles pass, the children are back at gobbling up life like it was a five-course Thanksgiving dinner.

Of course, there are the unfortunate persons who don’t quite comprehend this family dynamic, but they’re not anything new. My own childhood wasn’t exactly out of a Disney movie either. Anyone my age (and that’s pretty darned old) who claim children are less respectful and lazier today are deluding themselves or have really bad memories.

These families I watch from afar are of every socio-economic-political background. No one group can claim the virtue of family values, nor can one segment of society be labeled as less than desirable.

Cynics can say they haven’t seen this family quality around them. My suggestion is to get out of the house and try to make a positive impact in their community. That’s where they will find all the families that make us thankful to live here.