A few years ago, I made the trip of a lifetime and went to England. I rented a car in London and learned how to drive on the wrong side of the road. Which was easier than you’d think because the steering wheel is on the wrong side of the car too.

My plan was to drive west to Stonehenge and Wales, then turn north through the Lake Country and up into Scotland. I’d go east and down into the Midlands and back to London. I took a full month so I could see everything on my own schedule and not on a tour bus schedule.

Everything was going well until I reached this one open plain which was the location of a major battle of the War of the Roses. I paid my fee and went on the tour. Now the most interesting part—at least for me—was the guide’s explanation of a phenomena called the Dogs of War.

“This field was covered with dead soldiers,” he explained, gesturing to the broad green field. “When the sun set, surviving soldiers had only recovered a few of the bodies. In the dark the living soldiers retreated to their camp and the shelter of their tents.

“Around midnight, they awoke to the barking, growling and snarling of dogs,” he continued. “Many of the soldiers lit their torches and ran out to the battlefield. They held the torches high as they walked among the corpses, but they saw no dogs. They continued to hear the barking, howling and snarling, but they saw nothing but the bodies of their fallen comrades.

“The next morning when the soldiers resumed recovering the dead for proper burial,” he said in a lower, more ominous voice, “they saw than many of the corpses had their arms and legs ripped from them, and the limbs had been chewed beyond recognition.

“Thus began the legend of the Dogs of War,” the guide concluded. “Anyone foolhardy enough to venture into the battlefield at midnight heard the howling of dogs. Some received mysterious bites on their legs. And a few were never seen again.”

Back at the inn I sat down for supper with a few of the tourists and our tour guide. Everyone was hungry for more gruesome details, even as they ate their beef pies.”

“What would possess anyone to go into the battlefield alone at midnight,” I asked the guide.

“Courage,” he replied quickly, “but it was the courage of fools and not to be admired.”

After I retired to my bedroom, I could not sleep, thinking how I had, foolishly or not, never done a brave thing in my whole life. Why, I’d never been on a rollercoaster. Not even the little slow ones for toddlers. I decided that since I was sixty-five years old, I had better be brave now or else I never would be.

So at eleven o’clock I dressed and went downstairs. I saw that a few of the tourists and the guide were still in the bar, downing large mugs of ale.

“And where would you be going this time of night, sir?” the desk clerk asked.

I smiled and said, “I just want to go for a walk.”

“And where might you go on your walk?” the clerk inquired. He didn’t sound like he disapproved but there seemed a tinge of concern in his voice.

“I don’t know,” I replied with a shrug. “The battlefield, maybe.”

“Suit yourself.” The clerk averted his eyes and resumed his bookkeeping chores.

The battlefield was only a fifteen-minute walk away from the inn. The night air was a bit nippy but not uncomfortable. Clouds partly covered the moon, so I had to watch my step. Once I reached the historic site, I discovered the sky was now totally covered in thick, low-hanging clouds. I pulled out my little flashlight and looked at my watch.

Midnight.

And no howling Dogs of War.

Hmph. Just as I thought. I turned to return to the roadway leading back to the inn when I heard some rustling in the distance. I stopped to listen. The rustling developed into a rumbling which evolved into the distinct pounding of dogs’ feet. Soon after that, a howl broke through the dark silence.

My mouth flew open. I began turning in circles, trying to determine which direction the dogs’ barking was coming from. It came from every direction. There was no escape. As the howling became louder and louder, I fell to my knees and covered my head with my trembling arms. In no time at all, I felt the hot breath of dogs at my neck. I cringed, waiting for the sharp teeth to tear into my flesh.

But instead, I felt wet puppy licks. The scary growling became puppy yipping. Then it was over. I opened my eyes and stood. Looking around, I saw nothing and heard nothing but cricket song. I was in deep thought, pondering what had just happened when I heard a human voice.

“Hey, you!” It was the tour guide running toward me. “I came after you when the clerk told me what you were up to.” He held up his flashlight to my face, searching for bloody teeth marks. “You all right?”

“Yeah, sure.”

He leaned in for a closer look at my neck. “Do you know you got dog slobber all over your neck?”

“After I heard the barking, I dropped to the ground and tried to cover my head. Then the howling turned into puppy dog sounds. And I felt licks all over me.”

The guide took a step back and stared at me, as though he had never seen me before.

“Well, I’ll be. I thought I’d never see the likes of your kind,” he said in awe.

“And what kind is that?” I didn’t know how to take his comment.

“There’s another part of the legend which I rarely tell on the tour because its occurrence is too rare, well, I’d never seen it before in my lifetime. My grandfather said he had seen one of you when he was a lad, but I didn’t really believe you existed.”

“So, what am I exactly?” To be frank, I was beginning to feel a bit like a freak.

“You are that rare breed called a good, caring, gentle person.” He took the light out of my face. “Legend has it that if a good, caring, gentle person wandered into this field at midnight, as you did tonight, the phantom dogs would attack. But once they sensed that person was good, caring, and gentle, they would turn into puppies and lick the person as though he were a long lost friend.”

“But I thought dogs could sense fear, and I admit I was not brave when I fell down. I was afraid.”

“You just thought you were afraid. The dogs knew. They have that way about them. There’s an old saying around here. Never trust a man who doesn’t love dogs. And never trust a man a dog doesn’t love.”

Monthly Archives: October 2017

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Thirty

James Brown accidentally leaned on the coffin of Elvis Presley

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King, until the other owners bought him out.

While Hal Neely’s career began to wind down in the late 1970s and into the 1980s, James Brown was going through a difficult stage of life, too.

Brown’s music seemed to be following trends instead of making them. He didn’t quite know what to make of the disco craze and found himself in the position of being the older man in a young man’s business. Brown would have loved to work with Elvis Presley but that was not to be. Presley admired the work of Jackie Wilson, even though some of the people in his entourage preferred James Brown. Bob Patton, a member of Presley’s staff, recalled that “Elvis came to see him (after a show) and shook hands with him (Brown) but they weren’t close.”

When Presley died in 1977, Patton said, “James wanted to get into Elvis’s funeral. It was arranged to get a limousine to pick James up and take him direct to the house (Graceland) for the ‘viewing’ and everything. And James did that. In fact, when James was there, he was talking to Priscilla and a couple of people and he was standing next to the casket, leaning on it. Fred Davis (a former DJ from Texas who joined Brown’s organization) started to turn white. He says, ‘Mr. Brown, Mr. Brown.’ James looked over and says, ‘Can’t you see I’m talking to people?’ So Fred whispers to him, ‘Mr. Brown, you’re leaning on Mr. Presley.’ If James Brown ever turned close to white, that was it. It took him about a minute and then he recovered.”1

Brown, through his contract with Polydor, found a new fan base in Europe, and toured there regularly from 1977 through 1981. His last album for Polydor was recorded in Tokyo in December of 1979.2

“In destroying my sound, Polydor had cost me my audience, and it was around this time, 1979, that the record business in general collapsed,” Brown said in his autobiography. “They tried to take me over into disco. I was against it from the first. Disco had no groove, it had no sophistication, it had nothing. It was almost over anyway. I fought against doing it but finally gave in. They call the album, ‘The Original Disco Man.’ I was very unhappy with the result.”

After Brown finally terminated his contract with Polydor, he struggled to re-enter the American market. At first the only offers he received were shows being billed as “oldies.” Brown insisted that he was still a contemporary artist and preferred to have his songs called “soul classics.” Eventually he was booked into the rock club circuit in New York.

The development that reinvigorated Brown’s career was a series of cameo appearances in highly successful movies such as “The Blues Brothers.” “Dr. Detroit,” and “Rocky IV” and on television shows such as Saturday Night Live and Solid Gold. However, his nightclub appearances showed his embarrassing move into middle age. “Singer James Brown has found he can no longer perform those wild athletic leaps as he did of yore,” according to a review in the Los Angeles Sentinel in 1981. He attempted a split that “left him prone and reputedly too injured to open a new slated concert at Ripley Music Hall in Philadelphia.” His audience now was mostly white, according to Robert Hillburn of the Los Angeles Times, “both young fans wanting to sample their pop history and the older ones wishing to relive some memories.”3

The bottom literally fell out of James Brown’s career in 1988 after several arrests on drug-related charges. Even though he had appeared with President Ronald Reagan to promote the “Just Say No” anti-drugs campaign and released such songs as “King Heroin” and “Public Enemy No. 1,” he became addicted to powerful drugs including PCP.

In the spring of 1988 he was arrested several times for drugs, weapons and domestic violence offenses. In September he was again arrested after flashing a pistol and shotgun at an insurance seminar resulting in a long police chase which crisscrossed the Georgia and South Carolina state line. A South Carolina sheriff said Brown had been arrested seven times in an eighteen-month period.4

All these arrests culminated with the courts finding him guilty of evading arrest in South Carolina and of attempting to run down two state safety officers. Brown received six years in Georgia and 6 1/2 years in South Carolina which were to be served concurrently.

“I’ve been in slavery all my life, ain’t nothing new,” Brown said in an interview. “It just means I don’t have to answer a whole lot of phone calls. Ain’t nothing changed for me but the address.”5

1 The Starday Story, 165.

2 Record Makers and Breakers, 148.

3 Wilson Interview.

4 Ibid.

5 Williams Interview

When Maude Became Grandma

Unbeknownst to each other at the time, Janet and I were very practical. We both knew the most important task after high school was to learn a skill that would make us money the rest of our lives. After that was accomplished we looked for jobs. Once we had regular paychecks coming in, we started looking for someone to love and marry. We met at a conference dinner and started dating. She lived an hour’s drive away, so I proposed quickly. If she wasn’t interested in me, I wanted to know fast so I wouldn’t continue waste gas money on her. (Okay, we didn’t live like we were in a romance novel.) Once we were married we agreed we wanted to have two years to have fun together and learn to live together with as little conflict as possible. When we accomplished all that and the doctor confirmed that Janet had conceived, we announced it to her parents, Maude and Jim.

And we were not ready for the response.

After staring at us for a long awkward moment, Maude said, “Your cousin Patty Belle and her husband just bought a new car and their old one wasn’t that old—“

Jim interrupted. “Oh, Maude, you don’t know what you’re talking about. They bought that car five years ago….”

Not another word was spoken about our announcement. A couple of months went by before Janet couldn’t stand it any longer and she phoned her mother.

“Why did you ignore us when we told you I was going to have a baby?”

“Well, I assumed you just thought you were pregnant. After all, we waited eleven years to have you.”

Janet assumed she was pregnant because her doctor showed her conclusive scientific evidence that there was a bun in the oven. And the reason her mother waited eleven years was that she had an inverted uterus and could conceive only after a sledding accident flipped it. In actuality. Janet and Maude were both 27 years old when they conceived.

I can’t remember what finally convinced Maude that Janet was—as they used to say—in a family way. Maybe Janet got a signed note from her doctor: “To whom it may concern: the holder of this memo is indeed preggers. Yours cordially, Dr. certified obstetrician.” Or maybe Janet showed her the sonogram. But Maude would have thought Janet had accidentally swallowed a watermelon seed and it was sprouting.

Anyway, even though she had to admit the obvious, Maude still kept up a steady conversation on what other family members were up to, which was generally no good.

By the last month no one could deny Janet was on her way to mommyhood by the size of the baby bump. I didn’t know how she could maintain her balance. To keep herself occupied, Janet decided to decorate the small bedroom as a nursery. We put up zoo animal wallpaper on one wall and painted the other three yellow. She didn’t want the traditional pink or blue.

Maude didn’t want us to do anything with the bedroom until after the baby had been born and had survived at least three or four months of life.

I should have known better but I asked her why.

“If the baby were stillborn or died after a week or two, then the decorated room would make Janet sad.”

No, losing the baby would make her sad, not the color of the bedroom walls. Also, the room was already painted and papered. It was a little late to take it all out now, and expensive to put it back when the baby was okay. Finally, yes, we knew bad things can happen, but we always wanted to anticipate the best. We thought life worked out better that way.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Five

Sweet little Wallis Warfield

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in taking the Archbishop of Canterbury hostage and exchanging for an anarchist during the Great War by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be Edward the Prince of Wales.

Wallis Warfield sat on the edge of her bed in the Shoreham Hotel in Washington, D.C., a cigarette in one hand and a glass of champagne in the other. She stared at her new husband passed out because of sedatives she had slipped into his drink. He was tied, spread eagle, to the bedposts. It was the culmination of her grand plan to marry young and to marry well. She had debuted into proper society a year earlier in 1915. One could not marry well if one had not debuted and paraded herself in front of all the wealthy young men in town. When she had not found any suitable takers within a few months, Wallis struck out to greener pastures in Pensacola, Florida, where naval officers could be found splashing on the beaches every day. She picked out the one with the most potential and turned on the charm. Here less than a year later, he was her husband and her captive.

It had been quite a day. Exactly at 6 p.m. her uncle Solomon Warfield escorted her down the aisle at Baltimore’s Christ Church. Her father died of tuberculosis when she was an infant so his brother Sol filled in for him. Poor Uncle Sol. He twitched all the way to the altar and replied too quickly when the minister asked who would give this bride to her dearly betrothed. Wallis could not blame him much, considering he awoke one night to find his ten-year-old niece sticking a long hat pin into his left nostril.

“What the hell?” Sol awoke with a start.

“No, no, Uncle Sollie,” little Wallis whispered. “Don’t move. It will only hurt more. If I cram it in all the way it could go into your brain. You might die.” She giggled. “Isn’t that what you always say to me?”

“You’re crazy, Bessie,” he rasped.

“Don’t call me Bessie. That’s what you call a cow. If you say Bessiewallis together real fast I won’t get too mad. But I like Wallis the best. Just like my daddy’s name.”

Wallis did not remember anything about her father, but she understood he was a tough practical man. Her mother was witty and charming. Wallis believed she inherited all those traits and she was going to use them to her advantage.

“I’ll kick you and your mother out of the house. And where will you live then?”

Wallis wriggled the pin, causing Sol to muffle a cry. His face turned red.

“We are not moving out of this pretty house,” she replied calmly. “And you won’t tell anyone what I’ve done. Who would think a sweet little girl like me could do something mean and nasty?” She flicked the end of the pin.

Sol groaned. “Yes, oh god yes. Anything you say, Bessiewallis—I mean, Wallis. But, please, in god’s name, take it out. Take it out now, please.

“Hmm, okay, Uncle Sollie.” She began to remove the pin but quickly stuck it back in.

A full-throated scream escaped his lips. Tears ran down his fat cheeks. Wallis’ mother Alice ran in carrying an oil lamp just as her daughter removed the pin and slid it into the back of her nightgown.

“Good heavens, Sol, what’s the matter?” Alice asked.

He shook his head and started sobbing.

“I don’t know, Mommy,” Wallis replied innocently running to her mother and hugging her. “I ran in as soon as I heard him yell and didn’t see anything.”

Alice wrinkled her brow.

“You do believe me, don’t you, Mommy?”

After a pause Alice answered, “My, you are a fast little bunny rabbit, aren’t you?” She glanced over at her brother-in-law. “Well, Sol, as long as you are all right….”

All Sol could do was nod and wave at her.

“Perhaps it was a nightmare.”

“Of course, it was,” Wallis interjected. “Uncle Sollie eats too much at supper. You always tell him that, don’t you, Mommy.” She turned to him, smiled and shook a finger at him. “You shouldn’t put so much in your mouth, Uncle Sollie.”

“Oh Wallis, you care so much for your uncle, don’t you?” her mother sighed.

“Of course, Mommy.”

“Well, try to have pleasant dreams, Sol, please.”

“Yes, Uncle Sollie, dream of me, and everything will be all right.” Wallis could see a flash of dread across his sweating face.

“Come, Wallis, we must let Uncle Sol get his rest.”

“First I want to give him a good night kiss.” Wallis went to his bed and pecked him on the forehead. “Yes, Uncle Sollie, you must rest well so you can go to your factory tomorrow and invent more of those clever little gadgets of yours. You need to make lots of money to buy me pretty new dresses.”

How Mommy Saved me on Halloween

This ain’t no ghost. This is evil.

I’ll never forget the Halloween Mommy saved my life. It may seem odd for an old man to call his mother Mommy. When I was five I tried to say mother because I thought it sounded all grown up. We had just moved into an old house the night before Oct. 31. There was a knock at the door as we were still unpacking.

An old woman with no teeth and gnarled hands was on the porch.

“I see you got a youngin’.” Her voice was soft and raspy.

“He’s a good boy. He doesn’t make any noise.” My mother grabbed my hand and squeezed hard.

“Oh, I’m sure he is. Don’t mind me. I’m just the neighbor from across the street. Just came over to say howdy. I’ll let you get back to work.”

My mother let go of my hand and opened the screen door.

“I’m sorry. I forgot to ask your name.”

The old woman turned to smile. “Sadie.”

My father went straight to bed after supper like he always did because he had to be up and out of the house for work by six in the morning. And no one ever woke him up, no matter what was going on. It didn’t make any difference how funny the television show was I knew not to laugh too loud. Mother and I finally turned the set off and went to bed. The house only had one bedroom so I slept out on what we called the sleeping porch. She tucked me in and wished me pleasant dreams. I had barely fallen asleep when I heard someone coming up the back steps. The thumping made it sound like a man who weighed at least 250 pounds. I was scared but didn’t dare yell. Before I knew it, my mother came from her bedroom and stopped at the back door, putting her hand over her mouth. The footsteps went away.

“What was it, Mother?”

“Nothing.” She forced a smile on her face. “You know, I think I’ll just sleep out here with you tonight.”

The next morning after breakfast she took me by the hand and we walked across the street to Sadie’s house. Again her grip was like a vise and really hurt. I never dared say anything about it. Mother rapped at the door, and Sadie appeared, wiping her hands on a dishcloth.

“I thought I’d be seeing you again soon. So you heard the footsteps last night, didn’t you?”

I watched my mother bat her eyes and open her mouth but the words took a while to come out.

“I saw a man—a big man—on the back steps.” She paused before she blurted, “Who is he?”

Sadie put down the towel and stepped out the door. “Nobody knows who he is.”

“I can’t believe that. A man trying to get into someone’s house. Surely the police—“

“Nobody knows his name because he’s been dead for over a 150 years. He’s a ghost.”

“A ghost? That’s foolishness.”

“That’s what all the folks say who live in that house until one of the children go missing.”

I looked up at my mother’s face. Her lips were pinched. I knew when I saw that look I better go run and hide. Luckily she was mad at Sadie and not me.

“He shows up like clockwork every ten years at that house and a child disappears. Halloween.” She laughed, which wasn’t a pretty sight since she had no teeth.

Mother’s face wasn’t a pretty sight either. She was squinting her eyes and gritting her teeth. Get out of the way. She was about to blow.

“I’ve seen that look before, but it’s true,” Sadie said, wagging a crooked finger at her. “Even before the house was built. One night a wagon train came through and camped right here. Everybody heard the footsteps, crackling on the leaves and twigs. Then a woman screamed. Her little girl was gone, and there ain’t was a thing nobody could do about it. Some think it’s the ghost of some Indian, but that ain’t so. It ain’t an Indian or nobody else. It’s just pure evil.”

Mother squeezed my hand even more tightly. “It’s not nice to say things like that in front of a little boy, just to scare him.”

“He got scared last night before I said a thing, didn’t he?” Sadie didn’t wait for Mother to answer when she added, “I keep warning folks to order that thing to go away. He ain’t wanted here. They don’t listen to me. But you better listen. Show that thing who’s the boss.”

That night at dinner Mother didn’t tell my father about what happened, knowing he wouldn’t have believed her. He went to bed, and we watched television but didn’t find anything funny to laugh at. All the trick-or-treaters passed by our house. Finally we went to the sleeping porch. I was in my bed, and Mother sat in a rocking chair by the back door. I couldn’t sleep. Then we both heard it—the heavy footsteps on the back steps. Mother stood. I knew she planned on doing what Sadie told her—go away, this is my house, you’re not wanted here. At the last minute, she paused and cocked her head.

“I’m so glad you showed up.” It was her friendliest voice. “I’ve been waiting for you.”

The steps stopped. I sat up in bed and saw the hulking mass of—I don’t know, it looked like floating coal dust.

“I love you. Only you.” Her breath was like a soft panting now.

The dark figure stood still for a long time before turning and walking away. My mother rushed to hug me. I squeezed back.

“Oh, Mommy, I love you.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Thirty

Edwin Stanton

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Edwin Stanton held President and Mrs. Lincoln captive under guard in basement of the White House. He guided his substitute Lincoln through his first Cabinet meeting. Then he told Lincoln’s bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon into believing Lincoln and his wife were in hiding because of death threats. Lincoln’s secretaries realize something is wrong but are afraid to say anything. Janitor Gabby Zook, caught in the basement room with the Lincolns, begins to think he is president.

A loud knock at the door broke the tender moment Gabby and Mrs. Lincoln were sharing. Gabby began to dart for his corner behind the crates, but she grabbed his arm.

“There’s no reason for you to scurry off like a scared rat.”

“We don’t have any rats anymore. I caught them all. The traps going off in the middle of the night kept you awake, but I got rid of all the rats.”

Mrs. Lincoln’s grip on Gabby’s arm tightened as the door opened, and Stanton briskly entered, turned to lock the door, and then walked to the billiards table.

“I’ve scheduled several important meetings today, so I don’t have time to spend here.” He looked up. “Where’s Mr. Lincoln?”

“I’m reading election results, Mr. Stanton,” Lincoln called out. “I’ll be there as soon as I put on my shoes.”

Stanton sighed with exasperation, but stopped short when he saw the quilt in Gabby’s quivering hands. Gabby unsuccessfully tried to hide it behind his back.

“What’s that?” Stanton said, stretching himself to his full height.

“It’s—it’s—”

“It’s a lovely quilt made for him by his loving sister,” Mrs. Lincoln interjected.

“By his sister?” Stanton pulled out his pebble glasses and placed them on his nose, peering at the quilt. “Who gave permission for anything to be transmitted between the outside world and this room?”

“It’s just a quilt, Mr. Stanton,” Mrs. Lincoln said.

“Give it here.” Stanton snatched the quilt from Gabby.

“No, please.” His face began to twitch and his eyes to tear.

“There’s something in here.” Stanton pulled a pocketknife out and opened it. His stubby fingers roughly punched several of the squares.

“Yes,” Gabby said, trying to control his voice. “It’s…”

“You and your sister will regret it if you’re passing notes back and forth, sewn in quilts!”

“How ridiculous.” Mrs. Lincoln furtively turned to look into the curtained area where her husband sat. “Mr. Lincoln, please hurry.”

“No!” Gabby could not help the shriek in his voice as he watched Stanton rip through the material and pull out old, faded socks.

“I better not find any letters in here,” Stanton muttered as he slipped his hand into the socks.

“You fool!” Mrs. Lincoln slapped Stanton full across the face, knocking off his pebble glasses. “It’s just a quilt! Not everyone deals in evil plots, Mr. Stanton!”

“I’m sure Molly is sorry for striking you, Mr. Stanton.” Pulling his coat over his broad, bony shoulders, Lincoln appeared through the curtains and swiftly placed his large body between his wife and the war secretary. “I wish I’d a dollar for every swat on the head she’s given me.” He looked down at the quilt. “What’s this?”

“Part of some conspiracy cooked up by Mr. Gabby and his sister,” Mrs. Lincoln said, Southern acid dripping from each syllable. “Fortunately for us, Mr. Stanton has foiled their evil plot.”

“No, sir,” Stanton said. “Just a quilt.” He handed it back to Gabby.

“It’s not just a quilt, Mr. Lincoln. It’s a Gabby quilt.” Gabby caressed it as he fingered the damaged squares. “With holes in it.”

“Don’t worry about that, Mr. Gabby,” Mrs. Lincoln said. She looked imperiously at Stanton. “Will you be so kind as to provide me with thread and a needle so I can repair the damage you did to Mr. Gabby’s personal heirloom?”

Stanton arched an eyebrow. “Of course, ma’am.”

“Excuse me,” she said, turning to her curtained corner. “This unfortunate incident has fatigued me.” She disappeared behind the white French lace.

“So what do you wish to discuss today, Mr. Stanton?” Bending over to pick up Stanton’s glasses, Lincoln smiled. “The election results?”

“Don’t you want to withdraw to your corner also?” Stanton put his glasses back on his nose as he directed his attention to Gabby.

“No. I thought I’d sit out here for a while.” He took a chair on the opposite side of the billiards table and folded the quilt. “You know, I don’t get out much.”

“That’s absurd—”

“Mr. Stanton.” Lincoln shook his head. “Let’s proceed with our discussion.”

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Twenty-Nine

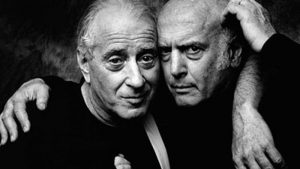

Lieber and Stoller, one-time partners of Hal Neely

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King.

In the early 1970s, the record industry experienced a loss of sales which could not be reversed. Pierce said Neely’s course of action was to record larger bands with fuller arrangements which did not help the financial status of Starday-King.1 The Bienstocks saw a different problem with the business operation in Nashville.

“I was at the Gavin Convention,” Johnny Bienstock said, “and I saw this guy (Neely) having a lavish party and everything else. I said to Freddy, ‘Starday-King Records must be doing phenomenally.’ He was treating jockeys like I’ve never seen; he was having bigger parties than Atlantic Records. Freddy was furious.” It was at this time the Bienstocks began to consider extricating themselves from the record company, even if it meant taking a financial loss. They were still interested, however, in the company’s song publishing catalog.2

“For whatever reason,” Wilson said, “the Neely, Bienstock, Lieber-Stoller situation became not as close or as productive as it had been initially hoped for, and the relationship there became sort of, well, at loggerheads. They being in New York – that is, Lieber-Stoller and Bienstock – and Neely in Cincinnati or in Nashville. Internal paperwork problems went unsolved because the people who needed to make such decisions were never in the same place at the same time. Beinstock, Lieber and Stoller in New York could only see the financial statements of recording costs.” Wilson felt they weren’t being informed about the rationale behind the numbers.3

The company endured mounting recording costs which had not been recouped. “I just visualized a lot of problems that maybe could have been overcome, given a little reinvestment money to pull the thing along,” Wilson said. “But I would be answering, really, to some people who had not been in the other end of the record business.” Lieber-Stoller and Bienstock had been involved in A&R (artists and repertoire) and publishing. Wilson and Neely were in distribution and marketing. “I just felt at the time, and this later came to pass, that their main thrust, all of a sudden, was not to perpetuate a record company but was to divest themselves of the record company and only keep the publishing end, which was really what happened.”4

Even Neely’s good friend Williams said he made a few bad decisions on producing new performers. He said one demonstration tape sat on Neely’s desk for months. Others urged him to produce it but he did not because he thought it was just a so-so song. The song “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” went on to be a big hit for another company.5

At one point Starday-King started selling off some of its real estate. Billboard Magazine reported in its Feb. 19, 1972 edition that Owepar, owned by Dolly Parton, Louis Owens and Porter Wagonner, bought Starday’s Townhouse building on Music Row to house its business activities.

In another effort to generate revenues, Starday-King released a second series of the Old King Gold catalogue, a collection of 31 rock ‘n’ roll and rhythm and blues singles from the 1950s, according to an article in Billboard Magazine in the Nov. 18, 1972 issue.

“What we did, originally, was to prepare a series of our King catalogue vintage tracks and turn them into pre-packaged sets which were sent to jukebox operators and one-stops,” Neely told Billboard. “Then all of a sudden we found we’re getting calls from underground college areas. This led us into our third pressing of the original series.” He said the company was planning to release a third in the series early the next year and eventually expanding to nine albums.

Business continued to decline, according to Pierce, and “after about a year and a half, the operation in Nashville was deeply in debt, and the Bienstock brothers came down and discontinued Hal Neely.”6

Eventually, Wilson said, Lieber, Stoller and Bienstock voted for Neely to resign as president, but Neely still owned one third of the Tennessee Recording Corporation.7

Neely gave a major interview with Billboard Magazine in its Oct. 6, 1973 edition. He said negotiations had lasted more than a week in both New York and Nashville over the Starday-King division of Tennessee Recording and Publishing Company. Neely told the magazine at first he was asked to resign. After Neely refused, the other three owners voted him off the board, while he retained his shares. The three men—Bienstock, treasurer; Lieber, secretary; and Stoller, board member—offered to purchase Neely’s percentage, and he countered with an offer to buy their shares.

“Neither offer was acceptable,” Neely said in the interview. “We were far apart at first, but we have been getting closer together. I am still hopeful of making the purchase.” He explained that the move began because Starday-King had not had a hit record for nine months. “I poured my own money into it, but there had been considerable disagreements over the way the firm should be run.”

Neely said if he were unable to buy out the other three, and they purchased his assets, he would immediately start another recording company and publishing firm. He owned a part of the physical properties and the existing catalogue through Neely Corporation Inc. (Review of Billboard files revealed Neely did not follow through with these plans.)

“If I should get out, I will be free and clear to enter business and compete.” Neely stressed he and the former partners were still “very friendly. It is now down to the point where the lawyers are involved for the most part, protecting their clients.” He said the company was still very healthy with the publishing company alone worth more than $1 million. He added that whatever debts existed were more than covered by the properties themselves.

Billboard reported that Bienstock said he would make a statement later in the week. (Likewise, a review of Billboard’s files showed Bienstock did not make any statement.) Lieber and Stoller were not available for comment. Neely concluded by saying if no agreement was reached that sale to a third party would take place.

The job of president was offered to Wilson, but he said, “I declined, because I could see the handwriting on the wall. And shortly after that period I resigned.” Wilson went on to work in the new distribution wing of Polygram, the parent company of Polydor which had bought James Brown’s contract.8

Don Pierce stayed on the Starday-King payroll for two years with an official title of advisor but actually took no role in the operation of the company. He bought a new home on the Old Hickory Lake, the same neighborhood where Neely lived. Over the years Pierce dabbled in real estate, automobile parts manufacturing, and established the Golden Eagle master achievement award for the country music industry.9

“Those guys (the Bienstocks) are only interested in the music publishing,” Pierce said. “That they won’t give up. They hold those copyrights and they know that those copyrights don’t argue. They just grow money. But they’re not in the record business. Take the records and get as much of it in the marketplace as possible. But we’ll do the publishing.”10

Looking around the music industry, the Bienstocks found a likely buyer in Gayron “Moe” Lytle, who with songwriter Tommy Hill founded Gusto Records in 1973. The company specialized in reissuing and licensing records from its catalog of acquired and self-produced music. 11

The Bienstocks originally wanted $500,000 for Starday and King masters and tapes in 1975. Pierce recalled Tommy Hill telling him, “Moe went up there, and laid down a check for $375,000. They (the Bienstocks) said, ‘You’re out of your mind.’”

Lytle picked up the check and said, “I’ll be at my hotel room.”

Hill said the Bienstocks discussed the proposition and decided that their business relationship with Neely was not working out right.

They didn’t have anywhere else to go,” Pierce said. “They didn’t know what to do with the masters. They don’t know a goddamn thing about records. They got all the songs but they needed someone to use those masters. So they took the $375,000. Imagine that! The whole King and Starday catalogs. Of course things were low ebb back then. They weren’t like they are now. It was just a different ballgame then.”12

In the deal, Gusto Records acquired thousands of master records and tapes which had been produced by King, Starday, and their subsidiaries. Included in the deal were all the record covers, photographs, promotional materials, contracts and other fan collectibles accumulated during the 30 years of running the companies. Lytle was quoted as saying he bought the masters because he wanted the Starday catalog and considered the King music just as an “add-on.” Gusto Records continued to own the King catalog which meant Lytle had now owned it longer than Syd Nathan.13

Master tapes generate immediate income upon the release to the public. They can become a source of quick and easy money but can also make it harder for a company to use its imagination and create new material. Gusto Records launched in 1978 a series of long-play records, cassettes, and eight-track tapes, which proved to be a treasure trove for fans and collectors. These records were affordable, plentiful, and easy to find.14

Tennessee Recording and Publishing, however, kept the publishing rights to thousands of songs on the King and Starday labels because this was considered to be much more profitable. Among the hit songs owned by the labels were “Fever,” “Dedicated to the One I Love,” “Please, Please, Please,” and “Work with Me, Annie.”15

During this same time Neely sold his interest in Tennessee Recording and Publishing Company to Beinstock, Lieber and Stoller. In his memoirs, Neely claimed who would sell out to whom was determined by a coin toss which he said he lost. Both Mike Stoller and business associates of the late Freddy Bienstock disagree with this story.

“I’m not quite certain what Hal Neely meant by a coin toss,” Stoller said. “With that image in mind, what did each of the heads and tails represent? My memory of the reason for the sale of the King and Starday Record catalogs to Moe Lytle was that Hal had spent a great deal more money (including his own compensation) than the company was earning. That resulted in the debts far outweighing the receipts of the company. Included among the expenses that Hal incurred was the purchase of a new bus for a recording artist who had had one successful recording. In regard to the sale, as I recall, the phrase ‘25 cents on the dollar’ was bandied about.”16

Bob Golden, vice president of marketing for Carlin America, Inc. — which was founded and run by Freddy Bienstock until his death in 2009–said he believed Mr. Neely’s memories of this transaction were probably inaccurate.

“I can verify that Freddy always considered and treated everyone in any business relationship he had as a colleague. He took great pride in the fact that all his dealings were scrupulously fair and square in a particularly hard and tough business.”17

Over a short period of time all employees of what had been Starday-King were dismissed, according to Wilson. “About the only operation that continued to exist until such time that Gusto Records bought the masters of Starday-King, about the only thing that continued to operate was the mail order operation, Cindy Lou’s Mail Order,” Wilson said. “Or as it used to be known, the Country Music Record Club.”18

“Hal never recovered from the Lieber-Stoller deal,” Wise said. “He never recovered in business. Hal was always the eternal optimist, but this was the beginning of the end.”19

Williams believed Neely sold Starday-King because he saw that major record companies, such as RCA and Capitol, were moving into Nashville and would put independents out of business. “He was right and wrong. The majors took over for a while but finally found it more feasible to let independents produce records instead.” 20

The music business was very volatile, Williams explained. For many years a company was able to make $60,000 in sales in juke boxes which created a market to small producers. Then juke boxes disappeared from the marketplace.

“The worst thing was to have a big hit. ‘Harper Valley PTA’ was a big hit but the producer went bankrupt. The printer had to borrow money from the bank to get copies out to the public before the sales came in.

“Hal was a great raconteur. He was an impresario and gave advice to young artists. Hal got involved in projects with that resume and storytelling, but when it came to putting the tread to the road he couldn’t do it,” Williams explained. “He got burned on many deals – including James Brown – and got shell-shocked. He got beat down. Hal was an easy mark and was taken advantage of. Hal bought himself a coal mine which blew his fortune. That mine was in War, West Virginia, near Welch. War had 300 people. Coal cost $200 a ton more to mine than it paid. He also decided to subdivide his lake property in the mid-1970s and lost money on that.”21

This was the time period during which Neely said in his memoirs that he and Wise acquired a condominium in Nashville. Williams remembered visiting Neely “when three guys came in the back door and ate in the kitchen. Each of us assumed the other one knew who the intruders were, but they were strangers. That was exactly what Nashville was. Nashville is a handshake and litigate. People don’t remember what the handshake was for.”

While Neely never lost his optimism and always thought a big deal was about to break, he did at times look back upon his career wistfully. Williams remembered him saying, “It wasn’t but a few years ago I could go into a bank and go up to the top floor to see the president. Now I can’t see the teller.”22

Others in Nashville did not take their music industry decline as gracefully. One time Faron Young asked Neely, “What do you do when you’re a has-been?”23 Young had been a top country music star from the early 1950s to the mid-1970s with hits like “If You Ain’t Lovin’ You Ain’t Livin,’” “Live Fast, Love Hard, Die Young” and “Hello Walls”. He also had made plenty of money in real estate and publishing the successful trade paper Music City News. But Young felt the country music business had forgotten him. At age 64, he committed suicide by shooting himself in 1996.24 His ashes were scattered over Old Hickory Lake where he had been Neely’s neighbor.25

“It was not the money but being a has-been,” said Williams, who entered his retirement years comfortably through investments in agricultural markets. “Soybeans have been very good to me.” He added, “I want to be remembered as being in bar fights and not as a 75-year-old man drinking grape juice.”26

The last story to appear in Billboard Magazine about Hal Neely was in its Dec. 1, 1979 issue, with a brief notice that he was now a salesman for a new Harlequin-type book series which he was pushing at Seibert’s Book Store in Little Rock, Ark.

1 Brian Powers.

2 The Starday Story, 165.

3 www.fundinguniverse.com_histories/lin_broadcasting_corp_history.

4 The Starday Story, 165.

5Record Makers and Breakers, 267-269.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., 271.

8 Ibid., 296.

9 Ibid., 438.

10 Tobler, John, NME Rock ‘n’ Roll Years (1st Edition), Reed International Books Ltd., London, 30.

11 Record Makers and Breakers, 233-234.

12 NME Rock ‘n’ Roll Years, 19.

13 The Starday Story, 165.

14 Wilson Interview.

15 Record Makers and Breakers, 148.

16 Dr. Art Williams Interview.

17 Ibid.

18 Winsett Interview.

19 Williams Interview.

20 Goldsmith, Thomas (editor), The Bluegrass Reader, University of Illinois Press, Urbana and Chicago, 2004, 193.

21 Ibid.

22 Williams Interview.

23 Wise Interview.

24 Williams Interview.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Four

Young David in a spiffy turtleneck

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in taking the Archbishop of Canterbury hostage and exchanging for an anarchist during the Great War by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be Edward the Prince of Wales.

No one seemed to notice the young prince enter the gymnasium and leave a few moments later to resume his run. David was quite pleased with himself—to murder someone who deserved to die. Even by his teen-aged years he learned the world was a dirty, rotten, stinking place where truth, compassion and honor and lying, dominance and greed were equally worshipped to the point of idolatry without any ambivalence. And there was nothing a good decent person could do anything about it. Well, he had some done something about it. His action stirred passions within him that rivaled even sexual ecstasy.

The rest of his time at Osborne was uneventful. Without their leader the other bullies lost interest in torturing the prince. He never developed any deep friendships but what of that? Part of his brooding view of life had no room for the fantasies of lasting friendship and the even more absurd concept of true love. He moved on to Dartmouth to continue his studies so he could enter the Royal Navy, leaving his sordid past behind and forgotten.

One day as he left his military tactics class, two gentlemen in unassuming navy blue business suits intercepted him and guided him to an awaiting sedan.

“Don’t be alarmed, Your Highness,” one of them assured him. “We are loyal subjects of the Crown. Very loyal subjects.” He paused to smile. “I’m sure you have heard of MI-6, his majesty’s, shall we say, secret service.”

David shifted uneasily. After all, he was a mere lad of fourteen. Yet he should have had the confidence of knowing one day he would be the king of England and therefore above reproach of the law. David still knew he had committed cold blooded murder.

“Please do not feel intimidated that you find yourself seated between two men in the back of a large black sedan. We at the agency have spent the last two months trying to arrange our meeting to be as private and inconspicuous as possible.” He paused to smile again. “So there you have it.”

“So there we have what?” David surprised himself by the assertive tone in his voice.

“Ah.” The second man patted the prince’s thin shoulder. “Good for you. You have cut to the chase.”

“And what might this chase be?” The back of David’s neck burned as he feared his secret may have been found out.

“As we told you, Your Highness,” the first man continued, “you’ve nothing to fear. We have nothing but high regard for you. Of course, as you may well have surmised by now, we are spies. More bluntly put, we murder in allegiance to crown and country.”

They knew. David should have never never assumed he would not have been found out. Have courage, he told himself. They did say they had high regard for him.

“Two years ago you attended the Royal Naval Academy at Osborne. While there you underwent intense hazing by a group of upperclassmen led by the brawny son of a car dealer named—“He looked over at his comrade and then at David before he pulled out a notepad and flipped through it. “Oh dear. I don’t seem to have his name here.”

“I won’t be able to help you with that,” David interrupted coldly. “I don’t remember the names of people I hate.”

The other man patted David’s shoulder again. “You see, I told you we made the right decision with this one here.” He nudged the prince. “I bet you haven’t lost a night’s sleep since then, have you?”

“No, I haven’t.”

The first man leaned in. “Your work was brilliant. Sudden. Cruel. You saw the fear in his eyes, didn’t you? Yet subtle. Spectacularly common. The case sat a full year in the Osborne magistrate’s office gathering dust. It was just by chance it came to the attention of MI-5. That’s our domestic agency. But you knew that, didn’t you? And what if you didn’t? You’ll know everything soon enough.”

Every muscle in David’s body relaxed as he realized what was being laid out before him. “Does the King know of this?” he asked, his tone still cold.

“Oh no,” the second man replied. “He doesn’t know anything. You know your old grandpapa’s piss has tuned to gin, don’t you?”

“Gin? I thought it would have been scotch.” David quickly added. “My father, the Prince of Wales, does he know?”

“Oh no. Not him either.” The first man wrinkled his brow. “No one in your family can ever know.”

David smiled. “That makes it all rather worthwhile, doesn’t it?”

The second man cleared his throat. “Please take a moment to consider the seriousness of this assignment, Your Highness. Spies rarely live long enough to see old age.”

The boy turned to look at him and raised an eyebrow. “You mean I’ll be killed? What of it? They have four more to take the crown if I die.”

The car ride lasted another hour or two. They explained to David that after he finished his studies at Dartmouth, he would enter a training mission in the fall of 1911 on the battleship Hindustan. And the world would know of it. The session was already planned. But he would learn things no king of England ever knew before. Next he would enroll in Magdalen College in Oxford, again with a special line of instruction. By 1912, David would embark on a tour of Europe, visiting relatives and learning new languages officially and extending his spy craft away from the public eye. Eventually, he would join the Grenadier Guards.

“And I cannot stress strongly enough, Your Majesty, all this will take time. You may not even hear from us for six months or a year at a time. You must have patience. This is a life time commitment.”

“However long that lifetime might be.” David relaxed into his new circumstances.

The second man asked, “Excuse the impertinence, Your Highness, but you have not been contacted by anyone else, have you?”

“Anyone else? You mean like the enemy, whatever nation that might be?”

“No, sir—I can’t continue this deference. Attracts too much attention. May I call you David, like your family does?”

“Of course you may. I rather like it. David the spy.”

“All kidding aside,” the first man interceded, “what my friend is trying to inform you is that we need not fear only a political enemy but an enemy that is far more sinister—an enemy that fights you for money, like a common whore giving herself up for sixpence.”

David sobered. “I would rather die.”

The memory was fresh on his mind, though it had been eight years filled with training, discipline, pain, fear and the inexplicable thrill of murder.

“David! David!” his father bellowed down the dining table at him. “What the blazes are you thinking about? Some common whore?”

“George!” Queen Mary was quite indignant. “If you continue to behave in such a boorish manner I will retire to my quarters immediately!”

The Prince of Wales smiled and murmured in a tone only his sister Mary and brother George could hear, “Common whore? Hardly. I only bed respectable wives of wealthy gentlemen.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Twenty-Nine

General Samuel Zook, Gabby’s uncle

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Edwin Stanton held President and Mrs. Lincoln captive under guard in basement of the White House. He guided his substitute Lincoln through his first Cabinet meeting. Then he told Lincoln’s bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon into believing Lincoln and his wife were in hiding because of death threats. Lincoln’s secretaries realize something is wrong but are afraid to say anything. Janitor Gabby Zook, caught in the basement room with the Lincolns, begins to think he is president.

“I used to like the military,” Gabby said, watching Lincoln retreat behind the curtain with his newspaper. “Uncle Sammy went to West Point first. He was the smart one in the family. He’s a general now.”

“Yes,” Mrs. Lincoln said in friendly agreement. “I’ve heard of General Samuel Zook. He may have his turn as commander of the Army of the Potomac before this war is over.”

“Now I don’t like the military anymore.” He paused to look down and bite his lip. “They said I killed my best friend Joe.”

“Oh no,” she gasped.

“That colonel said the whole thing was my fault. He said I was the one driving the team. I was supposed to be in charge of the horses, and I didn’t control the horses, and the colonel was hurt and Joe was killed.”

“But he ordered you to drive the carriage over your objections.”

“It didn’t make any difference, they said.” Gabby shook his head. “I was the one driving the team so I was the one responsible, they said. They said I was a murderer. They said they were doing me a favor by just throwing me out of West Point and not hanging me. They said—”

“Please, Mr. Gabby, no more,” Mrs. Lincoln said, holding her handkerchief to her face. “I can’t stand to hear anymore.”

“They told Mama and Cordie I was no use to them and for them to take me home.”

“That’s dreadful,” she said. “I’m sorry I had you tell me.”

“That’s all right.” Gabby tried to smile as he wiped a tear from his eyes. “Most days, I don’t even remember what happened. I just know I don’t think as good as I used to.” He shrugged. “I don’t know why I remembered everything today.”

“I’m so sorry for my behavior.” Mrs. Lincoln reached across the billiards table to touch Gabby’s hand. “If I’d known what caused your misery, I’d have been kinder.”

“I know.” He found the courage to squeeze her hand before withdrawing it. “I think—and please don’t get mad at me—you’re a little like me. Sometimes we can’t help the way we act.”

“Mr. Gabby, I do declare I think you’re more perceptive than many of the intelligent men running this war at this very moment.” She cocked her head coquettishly.

“Oh yes, I know I’m smart, except when I forget to be—smart, that is.”

“You must spend more time out here in the room with us, Mr. Gabby.” Mrs. Lincoln laughed as she stood. “You really must.”

“Thank you,” he said. “But I think that would make me too nervous.”

“I know all about being nervous. Well, as you wish.” She turned to go to her cot.

“Would you like a quilt?” Gabby asked.

“A what?” She turned to smile at him.

“A quilt,” Gabby explained. “My sister Cordie makes them. She made me one. Just a minute, I’ll show it to you.” Quickly padding to his corner, Gabby grabbed the quilt and brought it out, proudly displaying a crudely sewn composition of rumpled squares of old cloth of different colors, textures, and patterns. “Cordie calls them Gabby quilts. She named them for me.”

“How nice.” Mrs. Lincoln smiled as she touched it.

“She cuts squares out of old dresses, shirts, and things she has around, and sews two of them together with an old sock in the middle, and then she sews the squares together, and you got a Gabby quilt.”

“So each square is a memory of a loved one.” Her eyes sparkled as she stroked it.

He pointed to a square of dark brown. “Mama wore this dress all the time. And this,” he said, tapping a swatch of gabardine, “was part of Papa’s best suit when he was a lawyer.”

“How wonderful.”

“Oh, they’re really not worth much. Used to, Cordie would make fancy patterns with the squares. Now she just sews them up any old way. That way you can really use it. If you’re sick and feel like you need to throw up, you can just let it go on a Gabby quilt. It doesn’t make any difference.”

Mrs. Lincoln withdrew her hand.

“I haven’t been sick on this one.”

“Oh.”

“Cordie used to say Gabby quilts were like love. Love isn’t something pretty to look at. Love is for everyday use. When you get sick you can wrap up in love—like an old Gabby quilt—and feel better.”

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Twenty-Eight

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle.

Hal Neely was probably the main reason James Brown stayed with Starday-King as long as he did. In one anecdote from his autobiography, Brown recalled how badly an engagement was going at the Copacabana Club in New York City where his “raw, gutbucket” style was not appreciated by the sophisticated crowd. He even gave the Copacabana management back $25,000 and cut the second week of his run. He remembered Neely coming into his dressing room on his last night.

“James, I think it’s time to redo the band. They’re a super band, but it’s time for a change.”

“I think you’re right. We’ve gone about as far as we can go.”

Brown said they often discussed personnel changes to get “new energy and new ideas.” With Neely’s guidance, Brown enlisted Fred Wesley as the new group leader who played the trombone instead of the clarinet which was the instrument of the previous leader, thus changing the sound of the group.

On another occasion Neely was producing a Brown record called “Choo-Choo Locomotion” but the session was not going smoothly. “It was about two or three in the morning, and Mr. Neely said, ‘Why don’t you just play conductor and call off the names of the towns and talk about them?’” Brown claimed that was the first time he ever did a rap.

“One thing you can count on was a phone call at two or three in the morning,” Wise said, remembering the days with Starday-King and Brown. “James always wanted to talk after a performance.” One time Neely arranged for a group of girls to be at an airport on the tarmac to greet James Brown. The girls lost control and ran toward him, getting very physical. “They tore the buttons off his coat.”1

On another occasion Wise recalled flying to Miami with Neely to attend three concerts by Brown, who went without food between the three performances. Neely treated Brown to a meal, Wise said; however, they went to Sambo’s, which she found ironic.2

Neely created lyrics on paper napkins during luncheons with Brown during which they discussed the continued development of his career and music.3 Even with Neely’s personal attention Brown had problems with Starday-King management. He demanded payments in addition to his regular checks and wanted the company to pay $5,000 for leasing of a Learjet. Even while trying to extract as much money as he could from of the Nashville studio, Brown was making overtures to other record corporations, such as Warner Bros. But his escalating demand for more money became a sticking point for the entertainment giant.4

Jim Wilson described the hard process that Starday-King went through to decide it would be in its best interest to persuade Brown to look for another company. “Now, mind you, everything we put out on him was a hit record. Whether it was a hit or not, it was a hit. We sell records on it. And maybe deservingly so, but for a little company such as we were to have one strong artist (who) suddenly began to dominate everything, we found it difficult to develop and break in other acts. It was a corporate decision, probably. James’ advantage and to Starday-King’s advantage.”5

Long-time King attorney Jack Pearl said to Brown in 1971, “James, there is a company moving into the American market called Polydor, and I think you should be with them. I think they’re going to be very big in the business.” Brown said in his autobiography that he wasn’t interested in the deal. Before long he was approached by Julian and Roy Rifkin who talked him into considering their company which turned out to be part of Polydor, which was a worldwide conglomerate of record companies with Dutch and German ownership.

Neely encouraged Brown to sign with Polydor promising to help renegotiate a new contract with them. Neely was familiar with the European company in dealings over record distribution for King.6

“He made good on Mr. Nathan’s verbal promise to me that I would get 10 percent of the sale price of the masters,” Brown said. After the transfer of the personal services contract and title to the masters, we negotiated a new long-term contract with Polydor they gave me a substantial advance, a production company, a separate office so I could be independent from them, and artistic control of my work. There was some talk at the time that Mr. Neely might move over to Polydor a little later.”

Wise saw James Brown in Macon before his contact was sold to Polydor. She and Neely stayed at his house while attending a show in downtown Macon which Brown hosted for musical newcomers. “He was nice to newcomers,” Wise said. “James helped other people unless he thought they were a threat to him.” Her last memory of Brown was him coming down the stairs to greet them. “He had pink curlers in his hair,” she said. “I think they made him self-conscious.”7

During the negotiations with Polydor, Brown showed his skills as a businessman. Fred Davis, who was Brown’s banker and one of his bookkeepers at the time of the deal, said, “James Brown had his seventh-grade education, but there’s no telling what his IQ was. I remember times when we were sent a 30-page contract from Polydor. He (Brown) did get worked up about some things, and wrote a little note in the margin, and everybody in the courtroom would be bickering about it. Two years late, that elementary little side note would bite them in the ass. One little side note cost Polydor $4 million when it caught up with them.”8

Brown also sought the advice of Henry Stone who claimed to have been on his way from Miami to Georgia to sign Brown to a contract when Ralph Bass got to him first in 1956. “I was in New York at the time,” Stone said. “Got a call from James, saying, ‘You’ve got to help me out. I met at the American Hotel with the Polydor people and I’m not happy with what’s going on.’”

Brown’s demand that Polydor pay for his jet blocked the negotiations. “I said, ‘So look, he wants an airplane,’” Stone related. “You and I both know James is breaking wide open with a new generation of kids. You know that James is huge in the clubs of Europe—all over the world he is breaking out. So why are we arguing about a jet?”9

The deal was sealed, airplane and all. However, the major element which made the deal click was Neely’s participation. Neely was both the lead negotiator for Starday-King and the holder of the personal-services contract with Brown. He was going to make a lot of money either way.10

“It took a little of the pressure off our company,” Wilson said. “Artists like James essentially said, ‘Look I’m selling all your records. I want you to spend all your time, you know, working on my product.’ We were developing another group at the time, the Manhattans, who since went on to become big artists with Columbia. We were developing the new thrust back with the bluegrass artists. And things were rolling along.”11

In a press release, Polydor said, “James Brown will perform 335 days this coming year, losing as much as seven pounds each performance. In an average month, he will give away 5,000 autographed photos and 1,000 pairs of James Brown cufflinks. He will wear 120 freshly laundered shirts and more than 80 hours on the stage, singing, dancing and playing at least 60 songs on more than eight instruments.”12

What followed in the next couple of years were some of the biggest hits in Brown’s career. Unfortunately, music historians actually mark the deal with Polydor as the beginning of the end for James Brown’s career. In April of 1972 he sent a memo to Polydor which announced the following: “To all white people this may concern: God dammit, I’m tired. It’s been a racist thing ever since I have been here. Leave me the fuck alone. I am not a boy but a man, to you a black man.” He wished someone would buy him out.13

Polydor wasn’t very happy with Brown either. By the end of 1976 Polydor estimated that it had paid $1,514,154 to Brown as an artist, and loans to his production company. The next year Brown asked for another $25,000, but Polydor refused to give it and even tried to impound his airplane. When 1980 rolled around Polydor and Brown were discussing ways to break their contact. Negotiations, in fact, became quite nasty when a Polydor executive claimed “Hal Neely had absolutely nothing to do with any of Brown’s success! Fact!” This statement was cited by Brown and his advisers as revealing conclusively that Polydor was ignorant about the career of the entertainer.14

In his autobiography Brown would compare King Records “which had been my family for fifteen years” with Polydor. “Whatever King had been about, Polydor was the opposite. Every King act was individual; Polydor tried to make all their acts the same. King wanted to be an independent company with individual artists; Polydor wanted to be a conglomerate. King wanted to be a little company with big acts; Polydor wanted to be a big company with little acts.”

1 Wise Interview.

2 Ibid.

3 Hanneman Interview.

4 The One, 257.

5 Wilson Interview.

6 The One, 256-257.

7 Wise Interview.

8 The One, 258.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid., 257.

11 Wilson Interview

12 The One, 259.

13 Ibid., 313.

14 The James Brown Story, 151.