This New Year’s I’m making more of a revelation that a resolution.

For Christmas I played Scrooge in a production of my play What in the Dickens Happened to Scrooge? At the end of Act One I pass out center stage. During dress rehearsal, at the beginning of Act Two, I entered in darkness to take my place of collapse. Unfortunately, I forgot there were some stairs right in front of me so I took a tumble over them and crawled to my spot just as the lights went up. The only person who saw me fall was an actress right behind me waiting for her entrance. The rest of the play went on without a hitch. Even the director didn’t know I had fallen.

I was so proud of myself for being a trouper, afterwards I pulled up my trousers to show blood dripping down a swollen scrape on my shin to anyone who would look. The actress told how she saw me fall, roll and crawl but she didn’t realize how bad it was. One actor offered to bandage it and take me to the emergency room.

“No, no,” I said. “It hardly even hurts now. I’m glad I was able to make it through the show.”

I got so many “oohs” and “Are you sure you’re all rights” that I was on an endorphin rush all the way home. Then in the privacy of home I realized that if I had really been that much of a “the show must go on” type of guy, at the end of the rehearsal I would have gone straight to the dressing room, taken off my makeup, changed clothes and gone out front to give my fellow cast members a hearty “good job!” then limped to the car without saying a word about my leg.

It was at that moment the revelation came to me that I was nothing but an attention hog. (There’s another word that sounds like hog that might be more accurate but, this is Facebook and one must be polite at all times, mustn’t one?)

On one hand I could tell myself, “Of course, I’m an attention hog. I’m an actor. I’m a storyteller. I’ll sit under my tent all day in hopes of telling a story to a handful of passersby who might stop for a moment. I post stories on my blog in anticipation of getting a thumbs up or even a little heart.”

On the other hand, this teaches me to control my impulse to interrupt when people tell me about their lives. I want them to know how a similar incident happened to me, thereby turning the spotlight on myself. (By the way, I really do love staring straight into a spotlight.) And, believe me, every time I’m in a group when someone talks, I want to talk too. I think it’s genetic. Davy Crockett was my great-great-great grandfather, and he was known for telling tall tales.

Anyway, the best conversationalist is the person who can look into the eyes of a person telling their story, smile, nod and not say a damn thing.

I don’t know if I could keep a resolution to shut up, but at least I realize I should shut up. That ought to count for something.

Monthly Archives: December 2017

Burly Chapter Two

(Previously in the book: Herman anticipated fifth birthday on the plains of Texas during the Depression.)

One night after supper, mother cleared away the dishes and brought out a small chocolate cake—Herman’s favorite—with six flickering candles on it. She and Callie sang happy birthday while his father and Tad sat there and pretended to mumble the song. Herman had actually forgotten his birthday. But when he blew out the candles and tasted the sweet chocolate cake he remembered—only for a second—what his mother had said about a teddy bear. After everyone had finished the cake, his mother with a beaming smile on her face pulled out a bundle wrapped in butcher’s paper.

“I colored pictures on the wrapping paper,” Callie announced proudly.

For a nine-year-old girl with too many freckles she was very nice, Herman thought.

“What! He gets a present!” Tad exploded.

“Be quiet, son,” his father said softly but firmly.

“But he don’t do half the work around here that I do, and he don’t have to go to school!”

“Oh, shut up, Tad,” Called chided her brother.

“You shut up,” he retorted.

Tad was a big twelve-year-old but he looked like a pouting baby when he was angry, which was too often, Herman believed.

“Now both of you settle down before I take you out behind the barn,” their father warned.

“But it isn’t fair,” Tad whined.

“Shush,” his mother added, handing the gift to Herman.

“Not fair,” Tad said under his breath.

Herman was sad his brother was mad, but he put that out of his mind as he tore into the paper and what he found made him grin from ear to ear.

It was a bear made of burlap with buttons sewed on his arms and legs so that they could move. He had a sweet little smile sewn on his face. Two more buttons made the eyes.

“Ooh, how pretty!” Callie cooed, hugging Herman. “Isn’t it wonderful, Herman?”

Herman was speechless.

“Mama made it,” Callie told him.

“It was your father’s idea to use the burlap bag,” their mother said, smiling sweetly and nodding to her husband.

Herman jumped up, without thinking about the worms on his father’s arms, and ran over to hug him and kiss his rough, weather-beaten cheek. For the first time he could ever remember, he felt those long, strong arms fold gently around him and pat him softly. He stood quickly.

“Um, I’ve got to go see how the livestock’s doing,” he mumbled, rubbing his eyes with his hands and walking with long strides out the door.

Mother rubbed her eyes with a towel. “Time to clean up,” she announced crisply. “Callie, clear away the dishes.”

“Mama, can I play with my bear?” Herman asked timidly.

“Of course, dear.”

“What are you going to name him, Herman?” Callie said excitedly, leaning down to look at the bear.

“I don’t know,” he replied simply.

“Why don’t you name it after yourself,” Tad said with a nasty sound in his voice. “Baby.”

“Oh, shut up,” Callie spat, then turned back to Herman. “Since he’s made out of burlap, why don’t you call him Burly?”

Herman smiled. “Yeah. Burly Bear.”

“Mama,” Tad began to complain, “It ain’t fair Herman gets fancy toys and I—“

“It isn’t a fancy toy,” his mother interrupted. She sighed deeply, then pinched her pinched together. “And whether it’s fair or not—well, I’m just too tired to worry about it. Times are might hard, children. Things aren’t fair for just about everyone. Maybe Mr. Roosevelt can do something about it but for now, let’s just try to get along and survive.”

Herman turned for the loft ladder when Tad jumped in front of him, pointed his finger and made a silly face. “Baby, baby, baby,” he said in a cruel sing-song voice.

Callie ran over and kicked Tad in the shins and screamed, “You’re so dumb and awful! I hate you!”

Tad yanked Callie’s long, stringy hair. “Oh stay out of this!”

Tad and Callie began to fight and scream but stopped very fast when their father came through the door and bellowed, “Hey! What’s goin’ on here?”

Both of them tried to tell their side of the story but since they were talking at the same time their father couldn’t understand either one. “All right,” he announced, “I’ve had enough of this. You’re both going out behind the barn.”

With muffled protests Callie and Tad went out the door with their father. Herman was glad he kept his mouth shut because he knew what awaited them behind the barn, a paddling.

“Why does Tad always call me a baby?” Herman asked his mother.

She smiled and hugged him. “Why, you are the baby of the family. And you’ll always be my baby, even when you’re grown and as big as papa.”

“Gosh, will I be that big?”

“Yes. Now get ready for bed. Take Burly with you.”

When Maude Became Maude

When I think of my wife Janet’s mother Maude, I can’t help but recall a line from Gone With the Wind. Rhett Butler said of his daughter Bonnie Blue, “She is what Scarlett would have been if it had not been for the war.”

If Maude had not been forced to live through the Great Depression of the 1930s, perhaps her better qualities would have shone through more.

Maude’s father was the chief electrician for a coal mining company in southwestern Virginia which meant the family had a good company house and the older children were able to go to college. As the middle child, Maude became caregiver to her three younger brothers and sister. Her mother also gave her the responsibility of walking to the coal mine every day when the whistle blew to accompany her father home to make sure he didn’t stop in the bar along the way. A small girl didn’t have the actual ability to keep Daddy from going through those swinging doors and stagger back out an hour later. When he finally arrived home, her mother blamed Maude and not her father.

What a terrible moral burden to place on a child, predestining her to fail. Maude spent the rest of her life trying to keep everyone else away from moral turpitude; and, dammit, she was determined not to let her mother down.

When she was fourteen, her father died of tuberculosis, and the coal company kicked the family out of their house because no one there worked for them anymore. Whatever community standing that came with her father’s being the company electrician went away. The money went away. She remembered searching through all the furniture for a missing penny so her mother could mail a letter. The older children helped out the best they could, and Maude and the oldest of her younger brothers went to work. And they couldn’t expect help from the family to go to college either.

One of the bright moments of Maude’s youth was to take the train to the next town over to spend the weekend with her Aunt Missouri. Missouri’s children had all moved away, so she could devote every moment of her gentle attention on Maude. She counted down the days to Friday and the trip. On Thursday evening before she left, a neighbor lady came to visit her mother, bringing along her large, shedding dog. Her mother told Maude to take care of the dog while the neighbor shared the latest town gossip. By the time the woman finished and took her dog home, Maude’s sinuses began to swell from all the dog dander. The trip to Aunt Missouri’s house had to be canceled.

So when Janet and I began having pet dogs, Maude came up with plenty of excuses why we should get rid of them.

“If you didn’t have to spend all that money on the dogs then you could afford to get the children something they really want,” she told me once.

“But what they really want are their dogs.”

Maude arched her eyebrow, sighed in exasperation and muttered, “I suppose you’re right.”

Right before she died, Maude told the story of the canceled train trip to visit Aunt Missouri and how it was canceled because of dog dander.

Another time Maude told us how she was so tired of cleaning house she decided to lie on her bed and pretend she was in her coffin. Everyone in town came by to say how pretty she looked dead and told her mother how they were all going to miss her. Her mother ruined her day dream when she walked by the bedroom.

“You know you’re really not dead and just lying there is not going to get your chores done.”

With great effort and with a sense of martyrdom, young Maude arose from the dead to complete her obligations to the family, which, she was sure, her brothers and sister did not appreciate.

Maude never could sit down of an evening to watch television with the rest of us. She had to wash clothes, iron or fold and put them away. Something in the kitchen wasn’t clean enough. I think she was afraid her mother was going to come back from the grave to tell her to stop watching that silly television and get her chores done.

Of course, all this is speculation on my part. I must remember I wasn’t there, and all I had to go on was Maude’s version of these stories. Who knows what actually happened back then. All I knew was the Maude who survived the Great Depression.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Thirteen

Disappearing on the street in Shanghai.

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Soon to join the world of espionage is Wallis Spencer, an up-and-coming Baltimore socialite. David seduces a diplomat’s wife on a slow boat to China.

On a lower deck of the HMS Wyndemere Leon began to rouse from his sleep. By 1925 he had been on many missions for the organization but this was his first voyage to the Far East. He kept focused on creating memories to share with his mother. He could not tell anyone else in the village about his job, not even old Joe. Nor could he keep a journal of his travels. If anyone from the organization discovered he had a written record, no matter how inconsequential, he would be summarily executed. He smiled at the absurdity of it. He never knew anything to write down. For this assignment he found the necessary tickets in a pot outside his front door. First a ticket from Nassau to Panama and another from Panama to Shanghai. In China he would receive further instructions. What or from whom he did not know.

Leon glanced in the mirror and was not pleased. He looked like a clean respectable beach boy from the Bahamas, a step up from a scruffy young fisherman walking home after a long hard day on the boat in the Caribbean. Leon wanted the appearance of one of those mysterious men dressed in white linen suits, who lingered in the corners of the Nassau casinos puffing on imported cigarettes.

He could not chastise himself too much. Leon provided well for his mother and sisters. They didn’t have to be servants any more. His bank account was growing. He could afford a proper home. He had even taken a wife, a girl he had known all his life. She had laughed with him as they played in the surf. She cried with him when his father died. And now she was bearing his first child. His life of sin had been good to him. But he still wanted a white linen suit.

A day later HMS Wyndemere landed in Shanghai. A buzz from the gang plank at the other end of the liner drew his attention. Photographers held high flash powder trays and set them off at a slender elegantly dressed young man, posing at the bottom of the plank with a cigarette between his fingers. Leon looked away at the street to see a rickshaw with a coolie standing in front holding a sign, “Eleuthera.”

He walked to it, climbed in without a word, and endured a short, choppy ride to a hotel, a more respectable hotel than he was used to. That evening he ate in the proper dining room. Next to him were two older British gentlemen who had drunk more brandy than they should.

“Ambassador Chatsworth landed today,” one of them said.

“Is that so, Geoffrey?” the second replied, choking on his snifter. “What in the deuce is he doing here?”

“It’s that Shanghai Massacre mess last month.”

“Oh yes. The embassy mucked that up, didn’t they?”

“Yes, the embassy chief should be sacked,” Geoffrey announced.

“Wouldn’t that be admitting culpability? The King can’t have that, Liam.”

“I suppose you’re right, but it’s a bloody mess if you ask me.”

“You know who must be chortling over this? The damned opium overlords. As long as the government is in disarray they can do as they bloody damned please.”

Leon wiped his lips with a napkin and pushed away his plate. Perhaps that was why he was in Shanghai, to assassinate the British embassy chief to ensure continued political confusion. The waiter presented his check and moved on. Leon didn’t even look at him. When he examined the total he noticed in small letters at the bottom: “tomorrow noon marketplace.”

The sun was overhead and insufferably hot as Leon entered the bazaar. He wandered about looking at useless merchandise. The stuff sold in Freeport was better made and sold at cheaper prices. One show that caught his attention was a belly dancer. From what he could tell, under all that makeup was a Caucasian woman, skinny and not all that pretty. But she could move her hips and balance a sword on her head.

“Sir, sir,” a voice called to him. “Over here. Finest wood carvings from the Bahamas.”

Leon recognized the cue aimed at him. A toothless Chinese man extended a statue of a naked man and woman embracing. The man was too skinny and the woman’s bosom was too large. Leon waved it away, but the man pulled him closer.

“Look, look. See? Much better.”

As Leon regarded the rest of the merchandise the man slipped a small revolver in his pocket. He jerked away and walked behind a tall stack of Indian rugs. Slowly pulling the gun from his pocket, Leon read the note which stuck out of the barrel:

“Short fat bald white man in linen suit.”

This would be the day he would die. Leon knew there was no way to shoot a man in a crowded open space and escape unscathed. He hoped, at least, his mother would be properly compensated. Leon chose not to dwell upon his fate but rather chose to do his job well.

A clamor arose across the marketplace. He walked fast and with determination toward it. As Leon pushed his way through the crowd he spotted a short, fat, bald, white man in a linen suit. From the whispers around him, Leon realized this was the British embassy chief who had ordered the attack on the Shanghai students. The idle chatter he heard over dinner had been correct. With a deep breath, Leon pulled his revolver and took careful aim.

Out of nowhere a hand swooped down, knocking his gun away. An elderly Chinese man pushed him back into the crowd before storming toward the ambassador. The old man shouted a gibberish, a mishmash of Chinese dialects. The old angry man got close enough to spit on the official’s face.

“Look! Look! “A voice erupted from the crowd. “Man with gun! Look! Look!” People pointed in Leon’s direction.

The old Chinese man rushed Leon, pushing him away. “No complications!” the old man muttered.

Leon recognized the voice from years before. It wasn’t an old Chinese man. He was the man from Canterbury Castle. What was he doing there?

Police whistles blew. Uniformed Shanghai officers chased after them. As they ran by the belly dancer, she let her sword skip along the cobbled market place, causing the crowd to scatter, blocking the approach of the police.

The man grabbed the gun from Leon. “You don’t need that,” he grunted, pushing Leon down a narrow alley while he raced down the main thoroughfare.

Leon hid in the shadows and watched the man start taking off bits of his disguise until he revealed the persona of an ordinary British tourist, who leaned against a wall and lit a cigarette to watch the police run past.

That night Leon sat in the hotel dining room wondering how he would he get home. As usual his first tickets were one way. The room had been paid for one night. After he paid, he had no more cash on him. Leon berated himself for still thinking of himself as a street thug who mindlessly killed people so he could afford his next meal. He had money. He did not have to live like that anymore. He should learn to bring his own money on his assignments to deal with situations like this. A young Chinese woman dressed in a short dress flounced up and sat next to him.

“Hey, pretty boy. I give you good time.” Her hand went under the table and shoved a thick envelope between his legs.

The maître d arrived. “Excuse me, sir. She’s on her way out.”

She quickly leaned in to whisper in a completely different voice, “He’s dead. Good job.”

After the maître d dragged her off. Leon looked inside the envelope which included ship passage home and a huge stack of cash which he prudently chose not to count at that moment.

Candle in the Window

(Author’s note: I’m taking the week off. Merry Christmas!)

Buford hunched his shoulders as he trudged through the slush toward home after a long shift at the factory. He lived in a big city, though at times he forgot which city it was. Other times he decided it wasn’t worth the effort to remember what city it was because they were all alike anyway.

Then he reminded himself to be grateful he had a job. It was 1934, and most people were out of work. But his job drained his soul so much he could not enjoy the Christmas season. Besides that, he had no one to share his life with. Seven days before Christmas. What difference did it make?

In the gloomy twilight of his big city street, a glimmer caught in the corner of his eye. As he turned to look into a street level room of a tenement building Buford saw a young woman place a lit candle in the window. No one would have given her notice if she walked along the street, but flickering candle revealed her face in such a way that made him feel both sorrow and affection for her.

The next night Buford did not hunch his shoulders quite as much as he had before walking home. He automatically looked toward the tenement window. The young woman placed two lit candles on the sill. He studied her face as best he could and thought he sensed quiet desperation in the curve of her mouth. His sleep was restless that night.

The third night Buford thought he detected a tear glistening in her eyes as she put three candles in the window, and his heart began to break a bit. He hardly ate any of his supper at his boarding house and again had a restless night sleep. The vision of the young woman and the growing candle illuminations haunted him.

Buford’s step quickened the fourth night. His shoulders were full back, and his face took the sting of the sleet straight on. Hoping the woman would be putting out another candle, he dreaded seeing her face tinged with pain. There she was, in the tenement window putting down four candles. This time a sweet smile graced her face, which make Buford smile.

Work at the factory went swiftly for the next three days. Buford’s mind was filled with thoughts about the young woman. Would she place yet another candle in the window? Would the shimmering light reveal despair, hope or joy? On Christmas Eve Buford walked briskly toward the tenement building. He felt his heart beat faster. Would there actually be seven candles in the window? And would the angel be smiling? He was startled by the image that crossed his mind. Yes, she had become his angel.

When he stopped in front, he saw the young woman carefully place the seventh lit candle in the window. He could no longer contain his curiosity and affection. Buford went toward the tenement and tapped on the window. He smiled as she noticed him and raised the window.

“I’m sorry. I couldn’t help but notice you’ve been putting candles on the window sill for the past seven days.”

“Oh.” Her eyes widened. “I’m sorry. It’s just some silly dream I had.”

“Dreams are never silly.” Buford had never given much thought about dreams before now, but now he wanted to believe in them. “What did you dream?”

“Promise you won’t laugh?”

“I promise.”

“I dreamed Santa Claus told me to light candles for seven nights and I would get my Christmas wish.”

“And what did you wish for?”

“I wished for someone to love.” She smiled gently at Buford. “I think I wished for you.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Thirty-Seven

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Edwin Stanton held President and Mrs. Lincoln captive under guard in basement of the White House. Duff and Alethia find pretending to be the Lincolns difficult, especially with Tad coming down sick. Stanton interrupts their dinner to make sure Duff is not eating too much.

“I don’t see why you can’t eat what you want.” Alethia’s fingers covered his hand, quivering at the hair across his knuckles and the warmth pulsating from his skin. “You’re a big, robust man who needs his food.”

“You should have seen me back in Michigan.” He turned to smile at Alethia. “I was near three hundred pounds. Biggest man in town.”

“Oh my.” She fluttered her eyes.

“My body’s used to having a heap of meat on it,” he said, “not like Mr. Lincoln, who’s always been a bag of bones.”

“Prison must have been terrible,” she consoled Duff. “To lose all that weight.”

“I don’t like to talk about that.” He shifted uncomfortably in his chair, then stood and paced to the door. Pausing there, he hung his head. “Being here is like prison. Not getting to eat. Mr. Stanton’s mighty close to being a prison warden.”

“I thought the way he put his hand on your abdomen was disgraceful.” Alethia stood and went to Duff. “It was so unseemly.”

“I hate him,” he whispered. “I hate being here.” He turned to smile bashfully at her. “But not you. You make this bearable.”

“Why, thank you.” She touched his arm. “I feel the same.” After Duff pulled his arm away, Alethia looked back at her plate filled with food. She said, “If you wish to leave while I finish my dinner, you may. It must be frustrating to watch someone else enjoying food you can’t eat.”

“That’s very sweet of you, ma’am.” Duff walked to her chair and pulled it out. “It wouldn’t be proper for a husband to abandon his wife and let her eat alone.” He smiled. “Please. Sit. Enjoy. It smells delicious.”

Alethia gratefully sat and began to eat, thinking of his words—a husband and his wife. She wished that were true in the real world. Perhaps, after all this was over, she dreamed as she chewed on the collard greens. For the next half-hour they chatted and laughed, reminiscing about the pleasant times of the last two months, as though they were years of family memories—the irrepressible Tad, the lovely surroundings, the kind servants. In that suspended glow of romantic lies, Alethia felt happy, even loved. After she finished, she strolled to the stairs with Duff, who opened the door for her. She thought her heart would stop when he put his large arm around her shoulders. It was the first time Duff had ventured to make physical contact, and she held her breath, trying to keep from crying. They went into Lincoln’s bedroom where Alethia hoped Duff would dare make the impertinent suggestion that they spend the night in the same bed as man and wife. He removed his coat, hung it up, and then turned to smile at her.

“Good night, Mrs. Lincoln.”

Fruitcake for Christmas

Fred would have been the perfect catch for any young eligible woman—he was smart, kind, gentle, considerate and rich. His only problem was that he looked like a fruitcake. Not crazy like a fruitcake, but lumpy and round like a fruitcake.

Fred would have been the perfect catch for any young eligible woman—he was smart, kind, gentle, considerate and rich. His only problem was that he looked like a fruitcake. Not crazy like a fruitcake, but lumpy and round like a fruitcake.

Diane worked at his computer services company. As owner Fred found a reason to go by her desk everyday to see how everything was. She would look up from her paperwork, smile and say, “No problems.”

This smile was kind, professional and beautiful. Her straight glistening white teeth were framed by full red lips and surrounded by soft, clear skin. Her blue eyes showed respect, friendliness but nothing much beyond that.

Fred was devastated. He tried to find ways to show Diane that he was more than a good boss and all around good egg, but she never seemed to notice. He did impress her with his all-encompassing knowledge of the technical world of computers. Diane laughed at all his jokes because he really was a funny fellow. She went, “Aww” when Fred showed her pictures of his nieces, nephews and cousins who were always climbing over him in gleeful play. Diane was the first in line to pet Andy, Fred’s basset hound which he brought to the office often. But nary a romantic glint ever entered her eyes when Fred appeared at her desk.

He hoped that would change at the Christmas office party. Fred cooked all the cookies and snacks each year himself. Besides all his other talents, he was a gifted cook. Fred learned all the tricks of the trade from his grandmother who passed down loads of recipes guaranteed to make guests go “Yum.”

His ace up his sleeve was Grandma’s fruitcake recipe. Even people who hated fruitcake loved Grandma’s recipe.

“It’s good enough to make people fall in love,” Grandma told Fred with a wink. “Be careful. This is mighty powerful stuff.”

The day of the office party everyone had turned off their computers, put away their files and lined up at the long table filled with all sorts of goodies.

“Would you like some fruitcake?” Fred shyly asked Diane.

She shook her head politely. “I don’t eat fruitcake.”

“Why not?”

“How do I know this isn’t one of those fruitcakes that’s been mailed around the world a couple of times?” she said with a laugh.

“I baked it with fresh ingredients last week,” Fred replied, trying to hide his hurt feelings. “It’s been soaking in Jamaican rum ever since.”

Diane furrowed her brow a bit. “Oh, I’m sure it must be very good because you made it. Everything you cook is good. I just don’t like fruitcake.”

“How do you know you won’t like this fruitcake?” Fred asked. He didn’t want to sound too aggressive. “I mean, when was the last time you ate fruitcake?”

“I don’t know. An aunt sent it to me for Christmas.”

“Oh, then it must have been filled with all sorts of preservatives and chemicals.”

“You’re probably right about that.”

“Then why won’t you try my fruitcake?”

Diane reached out and lightly touched Fred’s arm. “I’m sure there are a lot of girls out there who like fruitcake and who would take a slice of your fruitcake willingly.” She paused. “But I don’t like fruitcake.”

Fred was beginning to feel a little frantic. His neck was warm, and he was sure his face was turning red. “Of course, everyone has a right to eat or not eat anything they wish.” He stopped and collected his thoughts. “But think of all the wonderful things they miss out on because they just assume everything that looks round and lumpy isn’t right for them.” He looked into her eyes. “Do you like a nice lean steak?”

“Well, yes.”

His heart started pounding. Fred could tell he was beginning to aggravate her. “How many times have you bitten into a nice looking steak and found it to be tough and stringy.”

“I guess a lot.”

“But it didn’t keep you from eating steak, did it?”

“No.”

Fred took a slice of the fruitcake on a paper plate and held it up. “I know this doesn’t look as delicious as a steak. But it doesn’t taste as bad as other fruitcakes you’ve seen. It’s my fruitcake. It isn’t like anyone else’s. It tastes good. It tastes good every time because I care enough to make it taste good every time.”

Pinching a bite off the slice, Fred carefully held it up to Diane’s perfectly formed red lips and held his breath.

She looked at him and then at the fruitcake, sighed and bit a portion from the slice in his hand. Diane looked up and her eyes widened. She ate the rest of the cake from his fingers, and smiled. Then the smile changed.

In those eyes, Fred could see the respect and friendliness, but now there was something else. Diane leaned forward, gently placing her hands behind Fred’s head and kissed him.

Wow, Fred thought, Grandma’s fruitcake does taste good.

9 ½ MINUTE CAN’T FAIL HOLIDAY FRUITCAKE

2 ½ cups of sifted flour

1 teaspoon baking soda

2 eggs, lightly beaten

1 jar (28 oz Borden’s Mince Meat)

1 15 oz Borden’s Eagle Brand Sweetened Condensed Milk

1 cup walnuts coarsely chopped

2 cups (1 lb. jar) mixed candied fruit

Butter 9-inch tube pan. Line with waxed paper. Butter again. Sift flour and baking soda. Combine eggs, mince meat, condensed milk, walnuts and fruits. Fold into dry ingredients. Pour into pan. Bake in slow 300 degree oven for two hours, until center springs back and top is golden. Cool. Turn out; remove paper. Decorate with walnuts and cherries if you desire.

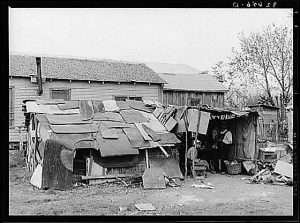

Burly Chapter One

Depression-era Texas farmhouse

(Author’s note: This is chapter one of my children’s novella Burly in which a little boy in Texas during the Depression received a best friend for life, a home-made burlap Teddy bear.)

Tiny rivers of rain rolled down the misty window pane by Herman’s bed in the loft of his parents’ farmhouse. They lived fifteen miles south of Cumby in North Texas, basically in the middle of nowhere. He didn’t know what time it was. All the thin sandy-haired boy knew was that it was wet, cold, dark, and he was lonely.

Now it was odd that he would feel lonely. His brother Tad lay in a bed not three feet from him and across the room behind a curtain held up with clothes line was his sister Callie. Downstairs in the room behind the kitchen were his parents. But still, Herman felt very lonely and very, very sad. Why should he feel this way? He didn’t know why; after all, he was only five years old. Soon the sad and lonely feelings became too strong, and little Herman began to cry softly until he finally fell asleep.

The next morning, after Callie and Tad had gone to school, Herman summoned his courage to talk to his mother about how he felt so lonely late at night, when everyone else was fast asleep. He didn’t dare mention it while he, his brother and sister ate breakfast. Tad, he knew, would have made fun of him.

“Mama,” he began hesitantly. “Do—do you ever feel sad and lonely—like at night?”

His mother stopped washing the dishes and looked quizzically at Herman with her soft gray-blue eyes. She brushed a wisp of light brown hair from her face and asked, “Whatever makes you say a thing like that?”

Herman shifted nervously in his home-made cane-bottomed chair and looked around the big room, first at the pot-bellied stove and then at the worn couch and chair in the far corner.

“Oh, it’s just that, late at night, when I can’t get to sleep, I start thinking that I’d like to have a friend.”

“Why, you have plenty of friends,” she replied with soft laughter. “There’s me, I’m your friend. And your papa. And Callie thinks you’re adorable. And your brother Tad–”

“I don’t think Tad likes me very much,” Herman interrupted.

“Oh, he’s your friend,” his mother reassured him. “It’s just he’s going through that age when I don’t think he likes anyone much.”

Herman almost added he didn’t think his papa liked him much either, but he didn’t because that really wasn’t what he was talking about.

“I mean, I want a friend my own age.”

His mother threw back her fragile head and giggled. “Well, there’s not much I can do about that. Living on a farm out here in the country like we do, we don’t have many youngsters running around for you to play with.”

“But still…” Herman’s voice trailed off. He knew his mother was right, and there wasn’t much use in talking about it anymore.

After a moment of silence that seemed as sad and lonely as the rain on the window pane, Herman’s mother said quietly, “You go on and gather the eggs in the hen house.”

“Yes, ma’am.”

He walked slowly through the front door and around the side to the hen house. He stopped short when he saw his father unloading sacks of grain from their old pick-up. His father never beat him nor had he ever said a harsh word to him. But Herman was still a little afraid of him.

Father was a tall, boney man who looked like he had long worms all over his arms. Mother tried to explain to him once that those were just papa’s blood vessels. They stuck out like that because papa wasn’t very fat, but he was very, very strong. Still, Herman thought they looked scary. Maybe they would not seem scary if his father ever hugged him, but he didn’t, so the fear still pestered Herman like a mosquito on a hot summer day.

“Hi, papa!” Herman yelled out, trying to be friendly. His father looked at him, grunted and went about his work. So Herman went about his own chores. He did have to admit he felt good about helping out. He brought in the eggs, kept the kindling box filled which was next to the pot-bellied stove and helped his mother set the table every evening. He went into the dark hen house and felt into the warm, downy nests to find eggs.

Soon he became aware of voices outside by the barn. It was mother and father talking. Herman knew it wasn’t very nice to eavesdrop, but he put his head to a crack in the hen house to listen anyway.

“Woody,” his mother said warmly but with just a touch of urgent pleading, “it would mean so much to the boy if we could give him a teddy bear for his birthday. It’s next week.”

“Now you know we can’t afford any fancy extras like toys,” his father replied wearily.

“Just this morning he was telling me how he wished he had a friend,” she continued. “A teddy bear, just a little stuffed something for him to hold onto at night so he won’t be afraid.”

Herman’s heart jumped a moment. A stuffed animal to hug at night. It was too good to be true.

“Opal, we just can’t afford it,” his father said in his voice that meant he was tired of talking.

Just then something odd happened. Peeking through the crack Herman could see his father looking down at the burlap bag underneath his hand. His father stroked it and patted it for a second then looked at his wife. She stepped closer to him, and they talked in low tones, so soft that Herman couldn’t hear them anymore so he went back to gathering eggs.

Herman didn’t think much about what his parents had talked about that day. The next weeks he was too busy gathering eggs and kindling and playing with rocks which he pretended were cars and trucks. He sang songs with his sister Callie and had a fight with his brother Tad, for which his mother gave them both spankings.

Grandpa’s Secret

Grandpa and Santa

Grandpa had a secret.

Little Jimmy learned what it was on late Christmas Eve as he sat with grandpa watching the tree lights twinkling.

“I can’t wait for Santa to arrive.”

“Me too,” Jimmy said. Then he looked at grandpa. “Why are you waiting for Santa?”

Grandpa gave him a big hug. “I’m going to tell you a secret. Do you promise to keep it?”

“Of course, Grandpa. We’re best friends.”

“Well,” he whispered, “I’ve seen Santa Claus every Christmas Eve for the last 80 years. I caught him leaving presents under the tree, and he said if I promised not to tell anyone he would grant me special wishes. For years I wished for toys. Then I wished to get into a good college. Then I wished I would make enough money to give my children everything they ever wanted.” He paused to wink at Jimmy. “Sometimes you wish you didn’t get everything you want.”

“What do you mean, Grandpa?”

“Well, I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed, but your daddy and your two aunts are awfully spoiled.”

Jimmy smiled. “Yeah, but I didn’t want to say anything.”

Suddenly there was a blast of cold wind and a soft “ho, ho, ho.”

“Well, James I see you have your grandson with you,” Santa said.

“Promise, Santa, I won’t tell,” Jimmy said.

“So, James, what’s your wish this year?”

”I don’t have a wish, except that Jimmy start having his wishes now.”

“He’s a good boy,” Santa said. “I think he can handle it. So, Jimmy, what do you wish for?”

“I just want grandpa to be happy.”

“Done.”

The next morning everyone gathered around the Christmas tree–grandpa, Jimmy, his parents and his two aunts. Jimmy opened each present and hugged and kissed his parents and aunts.

“Dad,” Jimmy’s father said, “you didn’t give Jimmy anything.”

“Yes he did,” Jimmy said spontaneously. “He introduced me to Santa Claus.”

“Introduce you to Santa Claus?” one of his aunts said with shrieking laughter.

Jimmy looked at his grandpa with terror. He had let the secret out. Grandpa nodded, smiled and told his family that he had visited with Santa for the past 80 years. Jimmy’s father scolded him for telling such silly tales to confuse the boy. The two aunts, almost simultaneously, accused grandpa of dementia, to which Jimmy’s father announced that if that were the case then grandpa had to be committed and all his funds taken into a guardianship handled by his three children.

“Oh, yes,” the other aunt added with an evil giggle, “I could take care of Daddy’s money very well.”

Tears filled Jimmy’s eyes as he sat in the judge’s chambers a month later with grandpa, his parents and two aunts. The judge sat at his desk and peered over his glasses at the stack of paperwork in front of him.

“I’m so sorry, Grandpa,” he whispered.

Just then there was a cold blast of air entered the chamber as Santa Claus appeared to Jimmy and grandpa. Everyone else was frozen.

“I wished for grandpa to be happy,” Jimmy said with a pout.

“But you were the one who told,” Santa reminded him.

“Is it too late for me to have a wish?” grandpa asked.

“No, I guess not,” Santa replied.

“I just wish this hadn’t happened.”

“Done.”

With another blast of air, Santa was gone, and the judge looked up from his papers.

“I’m sorry. What were we saying?”

“I was saying,” Jimmy’s father said, “my sisters and I have discussed it, and we think our father has given us more than we deserved throughout our lifetimes. We want our father’s will be changed so that everything will be left to his only grandchild, Jimmy.”

“Oh, I think that can be arranged,” the judge said.

“But Grandpa,” Jimmy said.

“Shh.” Grandpa put his finger to his lips. “It’s a secret.”

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twelve

Woodcut illustrating Shanghai Massacre

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be Edward the Prince of Wales. Soon to join the world of espionage is Wallis Spencer, an up-and-coming Baltimore socialite.

(Author’s note: this chapter contains mature situations.)

Lady Elvira Chatsworth could not contain herself. At the exact moment of climax with the Prince of Wales, she emitted a scream, a glass-shattering scream. Not that it mattered because it was eight o’clock in the morning in the prince’s stateroom aboard the HMS Wyndemere one day out from Shanghai. They had danced and drank champagne all night. Her husband, the ambassador, went back to his cabin because he had an important diplomatic strategy session that morning, which allowed her to have an experience of a lifetime—being bedded by the future king of England. And no one could hear a sound.

David nuzzled her neck. “I am pleased the British ambassador was so preoccupied with his staff that I had the opportunity of entertaining his wife.”

“Yes, he’s quite upset,” Elvira said, trying to keep her body from tingling for the third time. “Everyone at Downing Street is in a dither over this Shanghai Massacre scandal.”

“Massacre?” David asked as his tongue darted into her bellybutton, tasting her body. “What massacre?”

“Don’t you know about the Shanghai Massacre? It’s the current world crisis!”

“That’s why the Royal Family has prime ministers, ambassadors and such to worry about unpleasant matters.”

“Unpleasant indeed.” Elvira tried to continue even though her breath was becoming labored. ‘The embassy in April overreacted to a student protest and ordered soldiers out onto the street. Several students were shot down. Now we are in a fix. If we relieve the ambassador in charge it would been an admission of guilt which Great Britain cannot do. But we cannot ignore the entire incident. The empire’s reputation is in shambles.”

“And when did this happen?”

“April.”

“Of what year?”

“This year, 1925.”

“I’m shocked.”

“Of course! The whole world is shocked.”

“I thought it was still 1924.”

“You are such a naughty boy.” She giggled.

David drew himself up and planted a kiss on her lips. “Those things have a way of resolving themselves.”

Elvira turned her face. “You mean you don’t care?”

“My dear, I don’t care much about anything.” He smiled. “Right at this moment I care about you.”

“And why is that? Why are you always involved with married women? Why weren’t you interested in Princess Stephanie of Germany? What a diplomatic coup that would be. A royal wedding between Britain and Germany. But no. You’re mad about women who belong to other men.”

“But, right now in this place, aren’t you glad?’

“You cad.”

“That’s what my father calls me.”

“I know very most of the women you romance believe you will demand they divorce their husbands and marry you.”

David nibbled at her ear. “Gossip.”

“I loathe gossip,” Elvira announced.

“Rot. You love gossip. You did nothing but gossip about the affairs of London high society from midnight until the sun rose. You almost bored me to tears. Most of what you said was wrong.” He clucked her under the chin. “I know you can’t wait to disembark at Shanghai, have tea with the other ladies of the embassy and tell them you have slept with the Prince of Wales.”

“You are a scoundrel.”

“In fact, why don’t you tell them I am ill equipped to mount any woman and you spent the entire evening listening to me complain about my father?”

“How low can you be?”

“Oh, much lower. Tell them I’m a homosexual and am using all these wives as a cover.”

She slapped at his bare shoulder. “Why would you spread such lies about yourself?”

“If people keep busy spreading the lies they can’t figure out the truth.”

“And what is the truth?” For a flickering moment Elvira anticipated hearing some truly outrageous admission by the Prince.

“I want to make love to you one more time before breakfast.”

She studied his lean, tanned, handsome face. One eye squinted more than the other, making him more intriguing. She didn’t know why she pretended to be indignant. His reputation was as clear as a polished goblet. He traveled the world shaking hands for his country. And he shook hands like an expert. That was no gossip. Sliding down under the covers, Elvira smiled.

“As you command, Your Majesty.”