Nope, these pictures weren’t taken at the royal wedding. About a month and a half earlier. As it happens sometimes on group tours, choices are offered. You can either go to Windsor Castle or you can go to the Tower of London, but not both. Josh got the castle; I got the tower. Since I wasn’t there, Josh will supply the news about Windsor:

After the London tour, we split up into our respective groups: Dad went to the Tower (no pun intended) and I joined our lovely and talented long-term guide Fiona for our trip to Windsor Castle. The drive was an hour or so and once there we were led on a brief mini-tour of the outer courtyard. Like all castles in Ireland, Wales and England, the original purpose of the castle was as a military installation and position. However, both me and my kneecaps were grateful for the evenly cut stone steps. The guide mentioned that the moat area, as was with all medieval castles, were often filled with tar, sewage and god-knows-what other disgusting substances to impede the progress of an invading army. I can’t remember if it was Stuart or the temporary guide we had at Windsor, but it was mentioned that Windsor Castle in particular held a fond place in the Queen’s heart due to her growing up there. The guide mentioned that the Queen usually spent the work week at Buckingham Palace in London and came to Windsor to rest and recover. I couldn’t fault her choice in residence: the area around Windsor is absolutely stunning. Probably one of the most stunning facts was that the Queen was the only person in Windsor and England as a whole who did not have to drive with a driver’s license. The Windsor guide mentioned that this was because all driver’s license in the country were issued in the Queen’s name and authority. On one hand, it made sense not to issue a license to the one person whose name and authority were used for issuing purposes. On the other hand, I made a mental note to look out for elderly women in the driver’s seat whenever I was in England.

After the outside tour, my group, which consisted of several high school students, got in line for the main tour of the interior. All of the attendants dressed in the blue and red uniforms of House Windsor (for a heartbeat, I confused them with the local police) were walking up and down the line making sure no one took pictures. For the record, I did manage to take one picture of the interior but later deleted it from my cell phone. Let it never be said that a son of the Cowling family disrespected the house rules of royalty. Like the outside of the castle, the stairs were evenly cut and spaced. One of the first rooms we visited was the one where that horrible fire in the ‘90s started. I’m glad that the English really take care of their national treasures and monuments. While passing through, I couldn’t help but wonder how the heck was a thief going to fence all of the priceless art, tapestries, and fine china without causing a stock market crash, let alone get out of the castle alive with the goods. The tour took roughly an hour and when we exited we were right at the souvenir shop. Dad was writing a novel so I took the liberty of buying two or three books regarding the Royal Family and Windsor Castle. While waiting outside for the rest of the group, I was sitting with two or three teenage girls from are group and I saw a water-bottle machine that took 2 1-pound coins. I scrounged my pockets but only had one, so I asked my traveling companions if they had a spare coin. They started rummaging through their purses and I think it was the only blonde in the group who had a coin. I thanked her profusely and got up to get something to drink. When I got back, we started talking about the tour and trip in general when I realized how much the redheaded girl in our group looked like Sophie Turner AKA Sansa Stark from Game of Thrones. I asked her if she had been watching the series and she said only up to season three. I then asked if any one told her that she looked just like Sansa Stark because she certainly did. She thanked me generously and said no one had mentioned it before. I would have loved to go walking around the rest of the town but we finally had to depart for our final night in London itself. That was probably my favorite day of the trip because I was not only one of the group chaperones but also a surrogate older brother to the young ladies of the group. Heather, please sit up and take notes: THIS is how brothers and sisters should get along. Anyway, Back to you, Dad.

I went on the tour of the Tower of London with our teacher guide and her sister. As soon as we entered both of them said they felt like they had been there before. But not in the same way they said they felt like they had come home when we were in Ireland. As we walked around the grounds we found a water fountain memorial to everyone who had been beheaded on that spot. In the center was a lovely pillow carved from a clear quartz. It reminded me of the pillow used in fairy tales to hold a crown or a princess’s slipper. Then I remembered what landed on the pillow: a head. As the sisters went around the fountain both of them felt a bit queasy. They realized why the place seemed familiar, in a very uncomfortable way.

Inside we went through the line of historical exhibits on our way to see the crown jewels. The nice feature was the moving sidewalk on each side of the cases of crowns and scepters. Everyone got a nice close-up view without having to wait for someone to gaze upon the artifacts as though they were the only ones in the building. (We’ve all run into those types at museums before.)

Anyhow, here it is a month and a half later and my seventy-year-old body is still recovering. But I wouldn’t have missed this trip for anything

Category Archives: Non-fiction

Ireland and England with Jerry and Josh–The Best Tour Guide Ever

On our last morning to roam London, we got the best tour guide ever to give running commentary on the sights passing by the bus windows. If my memory serves me correctly—which it rarely does anymore–his name was Stuart. He matched from head to toe in shades of green, blue and gray. Even his shoes. I was hoping he would break into song and tap dance down the center aisle of the bus. But he was a proper gentlemen, and they don’t exhibit their choreography on public transport.

At one of our first stops he let us hop off the bus to examine the massive statue of Prince Albert. It was in a beautifully manicured park across the street from Royal Albert Hall. Unlike most people preserved for posterity in the many parks, squares and circles about London, Albert received full Olympus treatment. U.S. General Dwight Eisenhower was honored with a life-sized replica; others were remembered with a head and shoulders bust, and most were in bas relief plaques explaining who they were and why they were honored. But Albert, the royal consort to Queen Victoria and father to so many children I cannot begin to remember all their names, sits high, broad and proud. I do not know if the statue is gold or bronze, but it shone for all to see. This is magnificent memorial of a woman’s love for her husband.

Back on the bus, our elegant guide directed the bus driver past the monument to Lord Wellington. “Does anyone know what Wellington did?”

Josh piped up, “He beat the crap out of Napoleon.”

Stuart appraised my son a moment looked at our long-term guide and said, “I think I like him.”

A little while later we drove by a monument to King Henry VIII, who, Stuart pointed out, “had six wives. Do you know what else he had?”

“Syphilis,” I replied. Now I honestly was not trying to be a smart-ass and ruin the man’s monologue which was filled with wit and wisdom. But Henry did have syphilis and that was why the last years of his reign were so unfortunate for his subjects.

This time Stuart did not miss a beat and went on to explain that King Henry had a difficulty with forming long and loyal relationships. But surely in his mind Stuart must have thought that we two clowns were related. Yes, we are connected genetically and were born without proper filters.

Coming up on the right, he told us, was one of the many lion statues on the banks of the Thames River erected during the reign of Queen Victoria. Upon inspecting it, Victoria realized this lion was quite obviously a male, so she ordered its gender identifying appendage removed for propriety’s sake. When one looked at the face of the lion in question, one could surmise he did not agree with Her Majesty. His eyeballs are perpetually bulging in surprise and discomfort.

At one point we left the tour bus and followed our elegantly dressed Stuart on a saunter through Green Park, a serene space stretching out in front of Buckingham Palace. Ducks and geese glided across the serene surface of its lake. Locals jogged along its backs and lay on the grass, soaking up blessedly warm rays from a late-March sun.

Stuart had our stroll perfectly timed to end at the entrance of Buckingham Palace and the changing of the guard. As a mere former colonist, I thought the changing of the guard consisted of a hand full of soldiers in their bright red jackets and giant black fur helmets; but no, it was a full-fledged parade with horses, drums and rifles.

Stuart was careful to point out these were not just young men and women who were chosen for their proficiency for formal procedures. These were soldiers who had served their country in Afghanistan and where they might serve again in the near future.

When the last soldier had moved on, we broke up into separate groups to explore more bits of English historic lore. This was when had to wave a fond adieu to Stuart. I wish he could have stayed with us, but I am sure he had to address another bus filled with impertinent American tourists.

I really wanted to know who his tailor was, although I was quite sure I could not afford his wardrobe.

Ireland and England with Jerry and Josh–I’ve Seen Than Place Before

The movie fan in me had a great time in London. It was like being on the set of an Alfred Hitchcock movie.

Josh and I saw Royal Albert Hall, which like Big Ben, had scaffolding over half of it. Of course that means London is taking care of its architectural wonders so they’ll be around for years to come for American tourists to photograph. Royal Albert Hall was one of the big stars in the Hitchcock 1950s movie The Man Who Knew Too Much. The man in question was James Stewart, and he didn’t know too much. The bad guys just thought he knew too much. The big climactic scene was in the performance hall. When the man clashed his cymbals, a prime minister was to be shot and killed. I don’t want to give away too much in case anyone hasn’t seen the suspense classic, but Doris Day foils the bad guys when she doesn’t keep her mouth shut.

The next landmark featured in a Hitchcock movie was a tall church with an unusual red and white brick pattern to it. I instinctively recognized it but could not remember where. Josh, who was our official photographer of record, quickly took the picture but then went on to his next subject without helping me think of the movie title. It was only after we came home and were watching Foreign Correspondent one night did we make the connection. The foreign correspondent played by Joel McCrea was about to break a big story about German spies in a pre-World War II peace group when an assassin tried to push him off the church tower. The assassin went on to play Santa Claus in Miracle on 34th Street. Now that’s what I call avoiding being type cast.

The third landmark from a movie actually goes back to a famous stage play. I rested in Covent Garden in the shadow of the portico with massive pillars featured in the opening scene of My Fair Lady. If my theatrical trivia serves me right, the same façade is used in the stage versions of My Fair Lady and the George Bernard Shaw play on which the musicals were based, Pygmalion. In the movie and the plays, the building was supposed to be a concert hall, but in actuality it is part of the front of a church.

Now it is the scene of street performers. The entertainer I saw was very talented but he needed some lessons of audience appreciation. First he laid out a red rope at the perimeter of his performance area on the church steps and the cobblestone street in front of it. Woe be unto anyone who walked across the rope once the act began. One woman walked across it three times, and each time the acrobat with the wooden pins and sharp knives became more vituperative (it’s a British word; look it up) when she broke the rules.

“She’s so rude,” he announced to us, “that she doesn’t even know she’s rude.”

And I don’t think she did either. I know I was so scared by this point I didn’t dare scratch my nose. After his big finale I thought we spectators were safe from his acid tongue but I was wrong.

“I’m forty-eight years old and got a family to support here, so you can let go of some change,” he yelled. “Hey you! You mean you’re going to watch my show and walk away? You didn’t even applaud! The least you can do is toss a few coins in my hat!”

I took a fist of coins –I don’t know how much they were worth—put them in his hat and quickly exited stage right.

If Eliza Doolittle had been that aggressive in selling her flowers she wouldn’t have had to take those elocution lessons.

Ireland and England with Jerry and Josh–Touring Crazy Town

If you are going to one of the most exciting, eclectic cities in the world, go ahead and jump out of the bus into the heart of crazy London town and go for it.

The tour bus dropped us in Piccadilly Circus, and the guides told us to try to keep up. I knew immediately this was going to be difficult because how can you follow two typical English people in a crowd of a hundred thousand typical English people.

For the first thing, I was distracted by this building that had four gorgeous bronze statues of young nubile naked women diving into the center of Piccadilly Circus. Perpetually with their arms extended, up on their tippy toes, backs straight, tummies tucked in and chests proudly puffed out. I may be 70 years old but I’m not dead. By the time I realized I was supposed to be following the group, they were already across the street.

This presented me with my second problem. By nature I am always the one to step back with a smile and allow the cross pedestrian traffic to proceed. I have been known to hold open a door so long, people thought I worked for the store. If I did that in the middle of Piccadilly Circus, I would lose sight of my group and never see the Spanish moss draped live oak trees in downtown Brooksville, Florida, again. Then I remembered the grumpy old Irish woman with her walker in Dublin. I put a scowl on my face, hunched my shoulders and bulled my way forward. Before I knew it I was back with my group and I don’t think they had realized I had gone away.

This was very important to me. I’m old enough to be the grandfather of the young people on this student tour. The last thing I wanted was to have them interrupt their good time to see if the old man was lost, gasping for air, or fallen over with a heart attack. I didn’t want anyone to say, “Somebody call 9-1-1 and get the old geezer off our backs.” (Okay, they were all nice polite young American citizens and they would have never said that—thought it maybe. It’s a joke.)

Speaking of jokes, on the other side of Piccadilly was a street performer who looked just like Mr. Bean and for a modest price you could have your picture taken with him, hug him or pinch his bum. Twenty years and fifty pounds ago I was told I looked Mr. Bean. If I had moved to Piccadilly back then, think of the money and I could have made, and the bruises. Never mind.

Finally we arrived on Carnaby Street where the tour guides told group members to be back in two hours to eat at an authentic English restaurant featuring Indian cuisine. First Josh and I walked down the street to the largest toy store in London. The entire basement was filled with Star Wars stuff. My son Josh, by the way, goes to Star Wars convention everywhere, so he was in hog heaven (an old Texas expression). I, on the other hand, had reached the end of my tether and decided to go back to Carnaby Street while he explored the other three floors of toy heaven.

For the first time that day I felt entirely in my element. I ordered a nice lemonade, sat on the café patio and watched beautiful people go by as though they were on a runway. Unattractive people were beautiful in their high fashion clothes and perfect hairstyles. Even the boys. I wanted to see Twiggy walk by. Beatle tunes lingered in my brain. Everything was the same as when I was a teen-ager in Texas, except nothing was the same. I was old. And all the fashionable folk had smart phones stuck in their ears.

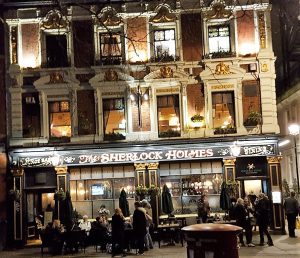

After dinner, the tour guides took us on one last marathon hike through Wellington Circle, past the National Museum and an establishment called Sherlock Holmes Pub. The tour guide said he used to work there. Finally we arrived at the Millennium footbridge over the Thames River where you could see the Eye (big Ferris wheel whose lights were down for the night) and Big Ben (which was covered in scaffolding and couldn’t be seen even if the lights were on.)

Don’t get me wrong. I had a great time. Who gets to walk the streets of glamorous London at night and not get lost? I didn’t have a heart attack. For someone my age that’s a great confidence booster.

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Epilogue

Epilogue

The intention of this biography was not to evoke pity for a man with a successful career whose final years were not lived in the same economic circumstances as the vast majority of his life. While others of his music contemporaries may have had more creature comforts, none were surrounded by warmer friendships.

While actual court records do not support Neely’s claim of a lawsuit, the underlying feelings about James Brown are nevertheless true. Brown was sued over royalties by an agent, but that agent was Ben Bart and not Hal Neely. Bart’s son Jack said Brown had a habit of “using, abusing and discarding” people throughout his career.1 Both Neely and Bart provided Brown with more than their expertise in the music business; they became surrogate fathers to him who consoled and counseled him during the rough times of his life.

One theme repeated by the many people who moved through Neely’s life was his generosity to artists coming up through the industry and to ordinary people he casually met along the way. Many people related their Neely stories with a smile and a tear. Some thought his generosity was a weakness in business, and perhaps it was. Better to be remembered as someone with a big, foolish heart than as a successful bastard.

As Neely himself said in his last interview, “The human brain remembers the good things…the good times…it rationalizes the rest.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Rarely are people privileged to help another person fulfill the dying wish of a dear friend. I thank Roland Hanneman for allowing me to help keep his promise to Hal Neely to have his memoirs completed. Roland spent many hours with me relating Hal’s stories and supplying names of other friends and acquaintances to fill in the enigmatic blanks of Hal’s life. I also thank Roland for introducing me to Hal at his nursing home so I could interview him for a local newspaper article the year before his passing. Roland’s devotion to his friend inspires me to be a better person.

Dr. Art Williams graciously spent several hours telling me about Hal’s years in Nashville and in Florida and providing valuable insights into Hal’s life and the inner workings of the music industry.

Some of Hal’s most vivid memories are of his second wife Victoria Wise and of her beauty. She agreed to meet me at a Tampa restaurant in 2011. I had seen only one photograph of her so I was concerned I would not recognize her, but when she walked in the door I instantly knew this was the woman who had enthralled Hal many years ago. I thank her for sharing her personal memories and for being the first person to challenge Hal’s claim he had sued James Brown in 2005. Victoria has recently remarried and I wish her all the happiness in the world.

I also appreciate the time and information from Al Nicholson, Buddy Winsett, Vic McCormick, Abe Guillermo, Sarah Nachin, and Bruce Snow whom I interviewed in Florida. I thank Ellen Paul of Brooksville, Florida, for her editing skills in preparing the final draft of this biography.

Those who spoke to me by telephone who provided assistance were Jack Bart, John Rumble, and Brian Powers. Mr. Rumble and Mr. Powers were kind enough to send me information from the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Cincinnati Public Library which proved invaluable.

Equally important were the e-mail communications shared with Mr. Bart, Randy McNutt, William Lawless, Nathan Gibson, John Broven, Cliff White, and Mike Stoller. Mr. Lawless, as Hal’s attorney, confirmed there had never been a lawsuit against James Brown. Mr. Gibson revealed hard feelings among Starday-King staff toward Hal. Mr. Stoller discounted Hal’s claim that he lost a coin toss and thereby lost his position at the Tennessee Recording Company. Mr. Stoller was the only celebrity who replied to my requests for information. As I said in my e-mail to him, I enjoyed his music and respected him for being a gracious human being.

In closing I thank my wife Janet for her memories about her grandmother’s fascination with Oral Robert’s radio program and about how she had ordered the small vial of Jordan River water which actually came from Hal Neely’s tap at home.

Epilogue

1 Bart Interview.

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Thirty-Three

Brooksville, Florida, Hal Neely’s last home

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King, until the other owners bought him out. He found himself sitting further back in music industry room. He eventually moved to Florida.

Brooksville, Florida, became Hal Neely’s best friend; both the town and the man were old, mellow, and had come to terms with their pasts. This friendship came about by accident. In 2005 Hanneman was returning to his home in Orlando from an appointment in Tampa when he took a wrong highway and wound up in this small town with old homes and streets canopied with Spanish moss-strewn oak trees. Brooksville’s out-of-the-way serenity struck a chord with Hanneman so he decided to build a house there. He realized that Neely’s health was failing and wanted him to move to Brooksville, too. After his doctor confirmed his condition, Neely agreed to give Hanneman power of attorney. At first he lived in a small apartment but soon moved to an assisted living facility called Tangerine Cove, a block from the old brick courthouse.1

Brooksville was founded in 1856, and citizens decided to name the town in honor of U.S. Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina after Brooks took a cane to U.S. Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts during an impassioned debate on slavery. Sumner made a disparaging remark about Brooks’ uncle, which provoked the gentleman from South Carolina to attack the older man from Massachusetts. Sumner took refuge under his desk as Brooks repeatedly swung his cane at him. Finally Sumner tried to crawl from the chamber but Brooks continued his assault. Blood stained the marble floor of Congress. Everyone in the north was horrified. Some historians pointed to the incident as the first bloodshed in the Civil War. Folks in the south, however, applauded Brooks, and the residents of a new Florida village took his name.2

By the first decade of the new millennium Brooksville had left its history behind with an integrated city council and bestowed its highest honor “The Great Brooksvillian” on a black civil rights leader of the 1870s who had been shot to death after performing a marriage ceremony between a black man and a white woman.3

Neely maneuvered about Main Street in his motorized chair, making friends along the way. The second Saturday of every month Neely rolled across the street and down a block behind the county library to a band shell. The local fine arts council received a grant to put on free concerts, and Neely attended every one of them, whether they featured garage bands, nostalgia rock groups composed of local teachers or special evenings of former stars, like the Coasters. When the grant money began to run out, Neely became a cheerleader throughout downtown to raise money to keep the concerts going.

One night he went to a downtown home decor shop where a martini reception was being held in honor of Carl Gardner, one of the original Coasters. Gardner was promoting his autobiography, “Yakety Yak I Fought Back.” Neely spun his wheel chair up to the desk where Gardner sat signing books and copies of CDs of his all-time hits, “Charlie Brown,” “Along Came Jones,” and “Little Egypt,” Every time a guest tried to take a picture Gardner put on his signature grin and gave a thumbs up. Neely, on the other hand, continued his conversation as though photographers were part of his everyday life.

“The music industry was filled with producers who were out to cheat you,” Gardner told the group. Then he pointed at Neely. “But this is the nicest man in the world.”

Because Neely was never voted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame or the Country Music Hall of Fame, he appreciated personal statements of gratitude like the one accorded him by Gardner, but many of his old friends and business associates–the ones who saw Neely in his prime–were disappearing.

His chief rival in claiming the discovery of James Brown, Ralph Bass, died March 5, 1997. Bass was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1991.4 His associate at King Records, Henry Glover, died April 7, 1991, and was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame in 2013.5 Loyal King associate Jim Wilson died Jan. 30, 1996.6 The brothers who brought about his demise at Starday-King, Johnny and Freddy Bienstock, died in 2006 and 2009, respectively.7 Songwriter Jerry Lieber died in 2011, survived by his partner Mike Stoller.8 Moe Lytle, whom Art Williams said Neely absolutely hated, was still running Gusto Records in 2013.9

In April of 2005 Don Pierce, with whom he had worked at Starday-King in Nashville died at age 89. He had not been voted into the Country Music Hall of Fame either.10 However, Pierce expressed feelings toward the end of his life about Neely that were less than friendly.

Nathan Gibson, author of “The Starday Story,” said Pierce specifically asked him not to involve Hal Neely in his project.

“As I understand it,” Gibson said, “when Hal took over at Starday, many believed he was the cause of Starday’s downfall…excessive spending, poor recording choices, clashing personality with many artists , business/personal relationship woes, and an overall carelessness for the business. Several individuals told me they loved Starday, best job they ever had, but they quit because they couldn’t stand working for Hal.”

During several interviews Gibson said participants told him that if he wanted to know about Hal Neely, he would have to turn off his tape recorder, and they would tell him about Hal Neely. The general feeling among those being interviewed was one of animosity and uneasiness.

“He remains a great mystery to me,” Gibson said, “and to many others.” 11

Those feelings were not shared by everyone. Author Randy McNutt said, “Hal was a good record man, and he was very helpful to me when I was writing the chapter on King Records for ‘Little Labels—Big Sound.’”12

On his birthday a call came into Tangerine Cove for Neely, and the staff could not believe it was Dolly Parton, who had done business with Neely and Starday-King. She wished him a happy birthday.13

Another fan was Al Nicholson, road manager for the Platters when the group toured in 1970 as part of the world’s fair in Okinawa. He also worked with the Drifters and the Coasters. By the middle 2000s Nicholson was entertaining in nursing homes in Florida, and during a performance at Tangerine Cove he looked into the audience to see a familiar face. He had met Neely while working with the Coasters. They renewed their friendship and spent many hours talking about old times, especially with Neely emphasizing his lawsuit against James Brown.

Ever the deal-maker, Neely used his influence with the organizers of the town’s band shell concert to feature Nicholson as an opening act.

“The crowd was screaming, and I had an autograph session with a line of thirty people.” Nicholson continued his visits to Tangerine Cove for long chats with Neely. “He was quite a character,” Nicholson said. “Sometimes he would get confused about his groups. But Hal’s stories were always consistent which gave the impression they were true.”14

Among his new friends were the members of the Brooksville Church of Christ which was about four or five blocks south of downtown. Neely’s grandfather was the first Episcopalian minister west of Mississippi. He grew up as a Methodist in Nebraska away from the influence of tobacco and booze. He was a self-described Irish/Scotch Protestant, joining and supporting the Presbyterian Church for many years. He felt right at home at the Brooksville Church of Christ.

One of his favorite activities in Brooksville was going to a Bible class taught by Abe Guillermo, long-time church member and lay minister. Neely called Guillermo the best damn Christian scholar he ever met.

After three months of going to church, Neely told Guillermo he was ready to be baptized. Neely said he had been raised in a Christian family and belonged to churches but never learned about Jesus until Guillermo taught him. Seventeen church members gathered at a member’s home for the baptism which was conducted in the family’s swimming pool. Neely approached the pool using his walker and gave a two-minute talk about his conversion. Guillermo gently guided him into the pool and immersed him in the water. Neely emerged exultant.

“I did it! I did it!”

If any of the church members thought Neely’s conversion was going to change his life-long use of common profanities, they were in for a disappointment. At the luncheon served afterwards, Neely spouted “damn this” and “damn that” a few times before Guillermo interrupted.

“Hal, we’re going to have to baptize your dictionary.”15

Neely had some regrets in his life, church minister Vic McCormick said he told him, but they were mostly in his private life. His first marriage ended in divorce, and there was a lot of bad feeling in his separation from his second wife. But he expressed no regrets in his business life.16

“Money was not my priority,” he told Guillermo. “You can’t change a thing. Now I have a new life.” He also told them he had warned James Brown not to go back to his same old crowd which had gotten him into trouble in the first place.

Brooksville accepted Neely as one of their own, albeit a man with a mysterious and exciting past. “To see him (Neely) you wouldn’t have known he had been big in the music business,” Guillermo said.

Another thing Neely told him was that he had his music catalogue in a warehouse. Originally he was going to leave it to University of South Florida, but he decided to give it to the Bible teacher instead. And he had royalties being held by a Memphis music company. Those would go to the church. His lawyer was a member of the Brooksville Church of Christ also. After Neely passed on, they were to contact the lawyer.17

***

James Brown died Dec. 25, 2006 of congestive heart failure and pneumonia at the age of 73. In his final years Brown was still performing and still the Hardest Working Man in Show Business. He scheduled eighty-one shows for 2006–including stops in Europe, Morocco, Tokyo, Estonia, Turkey and the United States.

He had also become a fixture in the charitable community of Augusta, Georgia. At Thanksgiving he gave away turkeys to poor families. On Dec. 20 he participated in a toy giveaway. He went to a dental appointment immediately after the toy distribution event, but when the dentist saw his physical condition he ordered Brown admitted to Emory Crawford Young Hospital where he died on Christmas Day.

Brown had three funeral services, one of which was at the Apollo Theater in Harlem where he had produced his live album with the help of Hal Neely.18

***

Guillermo said the London Times called Neely after Brown’s death and asked him how he was doing.

“Oh,” Neely replied, “I’ve found Jesus.”19

***

James Brown was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame in 1987 as was Syd Nathan in 1997, but the old King Records building in Cincinnati fell into disrepair and eventually into oblivion.

“In Cincinnati,” Larry Nager of the Cincinnati Enquirer said, “it’s as if King and Mr. Nathan never existed. There’s no museum and even a proposed historical marker remains controversial. Many say it’s because Mr. Nathan’s crudely direct style and the rawness of King’s music don’t fit Cincinnati’s refined, blue-chip self-image.”

“I’ll be surprised if the city recognizes the building,” Howard Kessel, an original King partner, said, “They never wanted anything to do with us. To them, we were just making records for hillbillies and black people.”20

***

Neely’s health continued to worsen, and Hanneman visited with him every day and ensuring he made all his doctor’s appointments. Sometimes Neely resisted going to see a new doctor.

Hanneman would walk in and say, “Come on, we’re late to your doctor’s appointment. You know the one. You’ve had it for months.”

He also showed up for meals just to make sure Neely made it to the dining room. Hanneman’s devotion to Neely stirred some suspicion among the personnel at Tangerine Cove. A staff member confronted him one day.

“Why are you being so nice to him?” she demanded. “You know he doesn’t have any money.”

“Of course, I do,” Hanneman replied, taken aback.

“So why are you doing this? People aren’t nice just to be nice.”

“He’s my friend.”

And he was. Hanneman bought Neely a laptop computer and encouraged him to write his memoirs. He listened patiently to all the stories, over and over again. There was a consistent theme. James Brown owed his success to Hal Neely, but never wanted to admit it. Brown was guilty of a “convenient memory.”21 Eventually, Neely wrote about 80 pages of memoirs.

The last interview Neely granted was in February of 2008 to a biweekly newspaper in Brooksville. The headline was “When Vinyl Was King.” He told the newspaper he first heard Frank Sinatra sing when the entertainer was 16 years old at a high school dance. “I asked him what he was going to be, and he said he was going to be a star. I told Harry James to sign him.”

He related how a man from Seattle had introduced Patsy Cline to him, and he signed her to a contract and produced many of her hit recordings. He said James Brown chose to forget him and his associations with him and repeated his story that he sued Brown in federal court in 2005. The article ended with Neely saying, “The human brain remembers the good things…the good times…it rationalizes the rest.”22

He developed stomach problems arising from the medications he was taking. As he slept Neely rolled over and fell out of bed catching his head between the nightstand and bedrail. He was taken to the hospital, and Hanneman was at his side as death drew near. Their eyes connected.

“I want my memoir completed,” Neely whispered to Hanneman. “People have to know that James Brown had a convenient memory. He didn’t want to admit that I had been the driving force in his early career. But I forced him to admit he knew me. It was in open court, and Brown had to face the facts.”23

When Neely died, many record industry officials came to the funeral service at the Brooksville Church of Christ on March 4, 2009.24 Neely’s cremated remains were left with the church, Hanneman said. Neely’s friend Art Williams did not attend; he was hospitalized in Phoenix, Arizona, for heart problems at the time. Williams said he felt hurt that Neely did not call him much in the last months of his life and he felt sad about the way he died. “Hal was genuinely interested in other people, optimistic and generous to a fault,” Williams said. “The pot of gold always eluded him.”25

Neely’s estranged wife Victoria Wise did not attend the funeral either. When she tried to file for benefits from his life insurance policy she ran across a clerical roadblock. When Neely’s death certificate was filled out, someone stated on it that he was divorced, even though they were only separated. Wise delayed filing the divorce papers. Neely’s friends had urged him to sue her for divorce in order to receive a monetary settlement from Wise, but the divorce never actually occurred. The insurance company chose to accept the death certificate as proof they had divorced.

“How do you prove a negative?” Wise said. “Hal always wanted to be appreciated and felt cheated he wasn’t recognized for what he did,” she said. When asked about the lawsuit against James Brown, she shook her head and replied, “There was no lawsuit.”26

After the funeral Hanneman went to Neely’s warehouse unit and discovered mementos of his career, which attorney Bruce Snow of Brooksville said were of no value.27 There was no record catalogue to be bequeathed to Abe Guillermo, which Guillermo said did not bother him at all. He just was pleased to have met such an interesting man from the record industry in the final years of his life, sharing their love of big band music.28 The Brooksville Church of Christ took possession of Neely’s ashes, Hanneman said. Snow also doubted there were any disputed royalties with a company in Memphis, as Neely had told his church friends.

“Hal’s recollection of events was colored by age,” Snow said. “His current and future plans were as mingled in thought as his history. Hal was not out to create grandeur that was not there. He had his grandeur, but it was a blend of reality and memory.”29

Snow’s hypothesis on the lawsuit was confirmed by William Lawless who represented Neely during the years he lived in Florida.

“The situation with James Brown happened a long time ago,” Lawless said, “In the early days of Hal’s career he represented James Brown as an agent. Brown shifted agents, and I think Hal sued on breach of contract. I do not know the results of that litigation.

“The lawsuit I handled was about compensation he earned while in the employ of a company (United Buyers of America). That lawsuit occurred more than thirteen years ago. My memory is poor on that subject. By the way, the arrangement with Hal regarding the lawsuit judgment collection was that Hal had so many friends in the business that he was going to locate the main assets and I was to seek a Writ of Execution to attach the assets.” He never found any assets.

“The last time I saw Hal, he was in western Florida in a place he was renting. There was a man with him who was cleaning and transferring music from albums to tape. This music is the music which Hal claimed he owned. One time I asked for documentation to see his ownership interest. He said he did not have any. Some of this was Frank Sinatra and other named singers.”30

An article in the Nov. 15, 1993 edition of the Orlando Sentinel reported that Neely, at that time 72 years old, filed a breach of contract suit in state Circuit Court in Orlando for $200,905 for pay from Jan. 1, 1989 to March 5, 1991 from United Shoppers of America Inc., a video duplication company.

Neely told the newspaper he did not press for his salary payment while working for the company because it was having financial problems. He was the corporation secretary, treasurer, chief operating officer and chief financial officer. He said he quit in March, 1991, because of not being paid and differences with management. After leaving United Shoppers of America Neely said he had worked part-time as a television writer and producer.

Roland Hanneman, when told that the lawyer involved with Neely during the time of the alleged James Brown lawsuit said the courts never had such a case before it, paused a moment and ran his fingers through his hair. The lawsuit was not important, he decided. The memoirs of Hal Neely’s long career in the music industry were more than one lawsuit against a singer.

Neeley’s memoirs were the cultural history of the United States in the last half of the 20th century. They represented in one man what life was for everyone: each person did his best according to the talents given to him and along the way he earned a few friends and made a few enemies.

In the end of his life Hal Neely was surrounded by friends, which was all that truly mattered.

1 Hanneman Interview.

2 www.fivay.org/hernando1.html.

3 www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CREC-2007-10-10/html/CREC-2007-10-10-PgE2115-3.html.

4 King of the Queen City, 93.

5 www.discogs.com/artist/308467-henry.glover.

6 John Rumble Interview 6/26/13.

7 www.legacy.com/NYTimes/obituary.aspx?n=freddy.bienstock. www.allmusic.com/artist/johnny.bienstock-mn0001010454/biography.

8 www.lieberstoller.com/abouthml.

9 The Starday Story, 166.

10 Ibid., 168-169.

11 Nathan Gibson Interview December 2010.

12 Randy McNutt Interview March 2011.

13 Hanneman Interview.

14 Al Nicholson Interview, June 2011.

15 Abe Guillermo Interview, March 2011.

16 Vic McCormick Interview, March 2011.

17 Guillermo Interview.

18 Life of James Brown, 197-198.

19 Guillermo Interview.

20 King of the Queen City, 191-192.

21 Hanneman Interview.

22 Cowling, Jerry, When Vinyl Was King, Brooksville Belle, Brooksville, FL, Feb. 21-March5, 2008 edition.

23 Hanneman Interview.

24 Neill, Logan, Grammy Award Winning Producer Dies, St. Petersburg Times, www.tampabay.com/news/article983842.ece.

25 Williams Interview.

26 Wise Interview.

27 Bruce Snow Interview.

28 Guillermo Interview.

29 Snow Interview.

30William Lawless Interview.

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Thirty-One

Manuel Noriega

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King, until the other owners bought him out.He found himself sitting further back in music industry room.

In 1989 Hal Neely and Victoria Wise left the problems of Nashville behind and moved to Orlando, Florida. They looked forward to new careers in music, film, and education based on the connections they had made over the years.

For example, Neely had been a judge in the Miss Panama beauty pageant which was part of the Miss Universe franchise. During this project he met a former diplomat to the Vatican and a retired actor who was a member of one of the seven families that formed the core of Panama’s society in the early 1900s. He also befriended President Manuel Noriega.

In Florida Wise wrote a screenplay called “Panama Bay,” an Indiana Jones-type adventure and encouraged Neely to find investors to finance it. Neely contacted his old friend Noriega, told him about the film project and talked him into spearheading it along with his other influential friends.1

Noriega was not exactly the best government leader to be doing business with at the time. He had a reputation as a corrupt and heavy-handed dictator.

Noriega came into this world under corrupt circumstances, the result of a liaison between an accountant and his maid in 1934. Five years later a school teacher adopted him. He received a scholarship to a military academy in Peru where he graduated with a degree in engineering. When he returned to Panama Noriega became a favorite in the Army of Col. Omar Torrijos. Noriega took control of Panama after Torrijos died in a mysterious airplane crash. His reign over the Panamanian people became so oppressive that the United States considered intervention.2

Neely and Wise apparently were more interested in their film project than keeping up with the current political situation. Even today, years later, Wise becomes enthusiastic describing the plot.

“The movie opened on the sea at dawn as a B-52 buzzed a hotel on a small island owned by a young woman named Hattie who came from a rich family,” Wise explained. “A vast treasure had been found on Hattie’s island.” This drew the attention of the Indiana Jones character which Wise called Ace. A love triangle developed between Hattie, Ace, and an old sea captain. Wise wanted the main characters played by Sheree North, Sheb Woolly and Burl Ives. “I had a lot of fun writing it,” Wise said. “I’m kind of glad no one changed it around.”

In December of 1989 Neely and Wise flew to Panama to scout out shooting locations for the movie. Noriega arranged for them to go through the exclusive route at the airport. After they got off the airplane, Neely showed Wise to the VIP lounge. As they were enjoying their cocktails, men in uniform escorted them to an interrogation room where they demanded to know what Neely and Wise were doing in the lounge. Neely said nothing but gave them a telephone number to call. It turned out to be the personal number of Noriega’s mistress. After the mistress explained the situation to the men in uniform, the officials were very polite and escorted them to their hotel. The next few days went very smoothly. Noriega gave Wise a necklace which consisted of two pieces of Plexiglas, one side yellow and the other side blue.

Then Neely got a call from the office of Tennessee Sen. Howard Baker telling him to leave everything, including his clothing and film equipment, at the hotel and go immediately to the airport to fly home.3

Operation Just Cause, a full-scale attack with 24,000 American troops, had just begun. Over the next four days several hundred American troops and thousands of Panamanian soldiers died. Noriega surrendered to the Vatican Embassy on January 3, 1990. The United States convicted him on drug charges, and the new Panamanian government wanted to try him on murder charges.4 “Panama Bay” was never produced, which became a pattern of behavior for Neely, according to his friend Art Williams who also moved to Florida in the 1990s. Neely became easily excited about business deals which never came to fruition.5

Perhaps the most fortunate meeting in Neely’s later years came at Orlando International Airport in 1989 when by chance he came upon musician Roland Hanneman who had brought a mutual acquaintance to catch a flight. After the man had boarded his airplane Neely and Hanneman realized they had quite a bit in common. The man who had just left them had taken them both for not inconsiderable amounts of money.

“He would shake your hand with one hand and give you a rubber check with the other,” Hanneman said. “Hal told me that this fellow had sold him music which he didn’t own and that he was always one step ahead of federal authorities.”

Over the next few years Neely and Hanneman worked on several small music projects. Neely produced albums for people in country and gospel music.

Hanneman, a native of Great Britain, is also known in the entertainment industry as John St. John. He studied music at the Cambridge College of Arts. After moving to the United States, Hanneman worked for Miami’s WINZ as production director. He has recorded and/or produced for the Miami Sound Machine, Mary Hart, Jon Secada, Clint Holmes, Jimmy Buffett, the Orlando Philharmonic and many more musical projects. He has written music for two Orange Bowl Shows and composed and/or produced more than 241 records and CDs. He has his own production company.6

“Hal was an extremely generous man and was always helping people. But he could see through people in seconds,” Hanneman said. “I would run people past him to get an opinion, and he was never once wrong about any of them. I asked him once how he could judge people so well and he replied, ‘I’m a hustler, and a hustler can always spot another hustler.’

Hal described his life as being fortunate to be in the right place at the right time and somewhat charmed, but he was always–to his dying day–looking ahead to some kind of business venture. It was difficult for him to accept the industry had changed and the paradigm had shifted. At one time, 200,000 records were a lot but now it’s half a million.”

Hanneman learned Neely’s technique of using ego to get his way with an artist. One time Hanneman was trying to get payment from a client who had recorded at his studio. Neely volunteered to get the money for him.

“Hal called the guy, identified himself as ABC Records and offered a record contract on his cassette and a plane ticket to California. ‘You do own all the rights, don’t you?’ Hal asked him.” Neely offered him $10,000 for the master tape remix. The man immediately called Hanneman for the master tape, but Hanneman told him he had to pay the full amount of the studio fees to get it.

“The next week he called Hal who told him this song might be used in a movie so he increased his offer to $25,000 and again reminded the man he had to have the master tape.” He called Hanneman again and agreed to pay the full amount and was at his doorstep the next morning with the cash. He received his master tape, but he never heard from the guy from ABC records again. 7

Neely’s relationship with Wise resulted in marriage in October of 1990, one day after his divorce from Mary Stone Neely was final. He was seventy years old, and she was in her middle forties.

Wise had fond memories of her years with Neely. They would pack a lunch and a bottle of wine, go on long drives in the country and have conversations about acoustic theories. For example, she said, boys between the age of 10 and 11 are at the peak of their hearing capacity to discern low-level tones. They even talked about the sound of wooden posts as they drove by would change according to the thickness of wood, speed of the car and spacing of the posts

“Hal would write letters with poor grammar to somebody about credit card issues, threatening lawsuits and saying he was sending copies to officials,” Wise said. “And then he would sign my name.”

Wise said she was bothered because she did not notice Neely’s decline into dementia but only concentrated on how hurt she felt during his emotional outbursts.

“He was like an angry gorilla throwing things.”

When Neely’s brother Sam came to visit them in Orlando they would wait at the curb right in front of a liquor store, Wise related. Sam went in, but when he came out he didn’t recognize the car. “I could see it (the cognitive decline) in Sam but not in Hal.”8

His finances began to decline also, to such an extent that Neely had to sell off personal items, Hanneman said. Neely had a Baldwin grand piano which had belonged to Liberace. Neely thought the provenance would make it more valuable, but he had trouble selling it for a good price. The person who finally bought it never paid for it.

Neely and Wise moved to an apartment in Tampa so she could study geriatrics at the University of South Florida.9

***

It was during this time James Brown was paroled from the South Carolina prison where he had spent 2 1/2 years of a six-year sentence. Upon his release in February of 1991 he announced a Freedom Tour.

“I am hotter now than I ever was in my life,” he announced to the press. In March of 1991 he starred in a live, pay-per-view concert from Los Angeles, and by the end of the year produced a new album “Love Over Due.”10

***

Neely’s marriage to Wise steadily declined throughout the 1990s while she continued her studies and eventually worked at the University of South Florida in Tampa. As she studied, Neely produced gospel music for small groups in central Florida. Eventually they separated in 2003, and Neely came to rely more and more on his friends Hanneman and Williams.

“Hal would come to my house to sit by the pool and cry about the way Victoria treated him and talked to him,” Williams said. “I told him to go back to Mary who had a farm in Nebraska.” When Mary died she left the farm to her family members who, according to Williams, detested Neely.

Sitting around the pool, Neely also complained about business deals which had gone badly for him, particularly the sale of Starday-King master recordings to Moe Lytle of Gusto Records.

“He hated this guy(Moe Lytle). They would tell anyone wanting rights to sell not to deal with the other one. Each claimed the same catalog. It ended in a stalemate with no one buying the rights. Hal was always involved with threatening to sue people and writing letters. One of his lawyers would filter them. He had no follow through on legal matters.”

Neely told Williams he was going to serve Wise with divorce papers but he never did.

“I told Hal to sue her for support,” Williams said

Williams also suggested to Neely that he should apply for Medicaid. “As long as Hal sat there and talked about his million-dollar catalog he wasn’t getting Medicaid. He had to admit he was broke.”

Another mutual friend told Williams he should help out Neely financially, but he declined. “I had lent him thousands of dollars over the years. People who loved Hal took care of him, and it may not have been the best for him.

“Hal never lost his optimism and always thought the deal was about to happen. The catalog deal was always about to break.”11

1 Wise Interview.

2 http://notable_biographies.com/Ni-Pe/Noriega_Manuel.html.

3 Wise Interview.

4 http://notable_biographies.com/Ni-Pe/Noriega_Manuel.html.

5 Williams Interview.

6 Hanneman Interview.

7 Ibid.

8 Wise Interview.

9 Hanneman Interview.

10 The Life of James Brown, 183.

11 Williams Interview.

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Thirty-One

Manuel Noriega

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King, until the other owners bought him out.He found himself sitting further back in music industry room.

In 1989 Hal Neely and Victoria Wise left the problems of Nashville behind and moved to Orlando, Florida. They looked forward to new careers in music, film, and education based on the connections they had made over the years.

For example, Neely had been a judge in the Miss Panama beauty pageant which was part of the Miss Universe franchise. During this project he met a former diplomat to the Vatican and a retired actor who was a member of one of the seven families that formed the core of Panama’s society in the early 1900s. He also befriended President Manuel Noriega.

In Florida Wise wrote a screenplay called “Panama Bay,” an Indiana Jones-type adventure and encouraged Neely to find investors to finance it. Neely contacted his old friend Noriega, told him about the film project and talked him into spearheading it along with his other influential friends.1

Noriega was not exactly the best government leader to be doing business with at the time. He had a reputation as a corrupt and heavy-handed dictator.

Noriega came into this world under corrupt circumstances, the result of a liaison between an accountant and his maid in 1934. Five years later a school teacher adopted him. He received a scholarship to a military academy in Peru where he graduated with a degree in engineering. When he returned to Panama Noriega became a favorite in the Army of Col. Omar Torrijos. Noriega took control of Panama after Torrijos died in a mysterious airplane crash. His reign over the Panamanian people became so oppressive that the United States considered intervention.2

Neely and Wise apparently were more interested in their film project than keeping up with the current political situation. Even today, years later, Wise becomes enthusiastic describing the plot.

“The movie opened on the sea at dawn as a B-52 buzzed a hotel on a small island owned by a young woman named Hattie who came from a rich family,” Wise explained. “A vast treasure had been found on Hattie’s island.” This drew the attention of the Indiana Jones character which Wise called Ace. A love triangle developed between Hattie, Ace, and an old sea captain. Wise wanted the main characters played by Sheree North, Sheb Woolly and Burl Ives. “I had a lot of fun writing it,” Wise said. “I’m kind of glad no one changed it around.”

In December of 1989 Neely and Wise flew to Panama to scout out shooting locations for the movie. Noriega arranged for them to go through the exclusive route at the airport. After they got off the airplane, Neely showed Wise to the VIP lounge. As they were enjoying their cocktails, men in uniform escorted them to an interrogation room where they demanded to know what Neely and Wise were doing in the lounge. Neely said nothing but gave them a telephone number to call. It turned out to be the personal number of Noriega’s mistress. After the mistress explained the situation to the men in uniform, the officials were very polite and escorted them to their hotel. The next few days went very smoothly. Noriega gave Wise a necklace which consisted of two pieces of Plexiglas, one side yellow and the other side blue.

Then Neely got a call from the office of Tennessee Sen. Howard Baker telling him to leave everything, including his clothing and film equipment, at the hotel and go immediately to the airport to fly home.3

Operation Just Cause, a full-scale attack with 24,000 American troops, had just begun. Over the next four days several hundred American troops and thousands of Panamanian soldiers died. Noriega surrendered to the Vatican Embassy on January 3, 1990. The United States convicted him on drug charges, and the new Panamanian government wanted to try him on murder charges.4 “Panama Bay” was never produced, which became a pattern of behavior for Neely, according to his friend Art Williams who also moved to Florida in the 1990s. Neely became easily excited about business deals which never came to fruition.5

Perhaps the most fortunate meeting in Neely’s later years came at Orlando International Airport in 1989 when by chance he came upon musician Roland Hanneman who had brought a mutual acquaintance to catch a flight. After the man had boarded his airplane Neely and Hanneman realized they had quite a bit in common. The man who had just left them had taken them both for not inconsiderable amounts of money.

“He would shake your hand with one hand and give you a rubber check with the other,” Hanneman said. “Hal told me that this fellow had sold him music which he didn’t own and that he was always one step ahead of federal authorities.”

Over the next few years Neely and Hanneman worked on several small music projects. Neely produced albums for people in country and gospel music.

Hanneman, a native of Great Britain, is also known in the entertainment industry as John St. John. He studied music at the Cambridge College of Arts. After moving to the United States, Hanneman worked for Miami’s WINZ as production director. He has recorded and/or produced for the Miami Sound Machine, Mary Hart, Jon Secada, Clint Holmes, Jimmy Buffett, the Orlando Philharmonic and many more musical projects. He has written music for two Orange Bowl Shows and composed and/or produced more than 241 records and CDs. He has his own production company.6

“Hal was an extremely generous man and was always helping people. But he could see through people in seconds,” Hanneman said. “I would run people past him to get an opinion, and he was never once wrong about any of them. I asked him once how he could judge people so well and he replied, ‘I’m a hustler, and a hustler can always spot another hustler.’

Hal described his life as being fortunate to be in the right place at the right time and somewhat charmed, but he was always–to his dying day–looking ahead to some kind of business venture. It was difficult for him to accept the industry had changed and the paradigm had shifted. At one time, 200,000 records were a lot but now it’s half a million.”

Hanneman learned Neely’s technique of using ego to get his way with an artist. One time Hanneman was trying to get payment from a client who had recorded at his studio. Neely volunteered to get the money for him.

“Hal called the guy, identified himself as ABC Records and offered a record contract on his cassette and a plane ticket to California. ‘You do own all the rights, don’t you?’ Hal asked him.” Neely offered him $10,000 for the master tape remix. The man immediately called Hanneman for the master tape, but Hanneman told him he had to pay the full amount of the studio fees to get it.

“The next week he called Hal who told him this song might be used in a movie so he increased his offer to $25,000 and again reminded the man he had to have the master tape.” He called Hanneman again and agreed to pay the full amount and was at his doorstep the next morning with the cash. He received his master tape, but he never heard from the guy from ABC records again. 7

Neely’s relationship with Wise resulted in marriage in October of 1990, one day after his divorce from Mary Stone Neely was final. He was seventy years old, and she was in her middle forties.

Wise had fond memories of her years with Neely. They would pack a lunch and a bottle of wine, go on long drives in the country and have conversations about acoustic theories. For example, she said, boys between the age of 10 and 11 are at the peak of their hearing capacity to discern low-level tones. They even talked about the sound of wooden posts as they drove by would change according to the thickness of wood, speed of the car and spacing of the posts

“Hal would write letters with poor grammar to somebody about credit card issues, threatening lawsuits and saying he was sending copies to officials,” Wise said. “And then he would sign my name.”

Wise said she was bothered because she did not notice Neely’s decline into dementia but only concentrated on how hurt she felt during his emotional outbursts.

“He was like an angry gorilla throwing things.”

When Neely’s brother Sam came to visit them in Orlando they would wait at the curb right in front of a liquor store, Wise related. Sam went in, but when he came out he didn’t recognize the car. “I could see it (the cognitive decline) in Sam but not in Hal.”8

His finances began to decline also, to such an extent that Neely had to sell off personal items, Hanneman said. Neely had a Baldwin grand piano which had belonged to Liberace. Neely thought the provenance would make it more valuable, but he had trouble selling it for a good price. The person who finally bought it never paid for it.

Neely and Wise moved to an apartment in Tampa so she could study geriatrics at the University of South Florida.9

***

It was during this time James Brown was paroled from the South Carolina prison where he had spent 2 1/2 years of a six-year sentence. Upon his release in February of 1991 he announced a Freedom Tour.

“I am hotter now than I ever was in my life,” he announced to the press. In March of 1991 he starred in a live, pay-per-view concert from Los Angeles, and by the end of the year produced a new album “Love Over Due.”10

***

Neely’s marriage to Wise steadily declined throughout the 1990s while she continued her studies and eventually worked at the University of South Florida in Tampa. As she studied, Neely produced gospel music for small groups in central Florida. Eventually they separated in 2003, and Neely came to rely more and more on his friends Hanneman and Williams.

“Hal would come to my house to sit by the pool and cry about the way Victoria treated him and talked to him,” Williams said. “I told him to go back to Mary who had a farm in Nebraska.” When Mary died she left the farm to her family members who, according to Williams, detested Neely.

Sitting around the pool, Neely also complained about business deals which had gone badly for him, particularly the sale of Starday-King master recordings to Moe Lytle of Gusto Records.

“He hated this guy(Moe Lytle). They would tell anyone wanting rights to sell not to deal with the other one. Each claimed the same catalog. It ended in a stalemate with no one buying the rights. Hal was always involved with threatening to sue people and writing letters. One of his lawyers would filter them. He had no follow through on legal matters.”

Neely told Williams he was going to serve Wise with divorce papers but he never did.

“I told Hal to sue her for support,” Williams said

Williams also suggested to Neely that he should apply for Medicaid. “As long as Hal sat there and talked about his million-dollar catalog he wasn’t getting Medicaid. He had to admit he was broke.”

Another mutual friend told Williams he should help out Neely financially, but he declined. “I had lent him thousands of dollars over the years. People who loved Hal took care of him, and it may not have been the best for him.

“Hal never lost his optimism and always thought the deal was about to happen. The catalog deal was always about to break.”11

Footnotes

1 Wise Interview.

2 http://notable_biographies.com/Ni-Pe/Noriega_Manuel.html.

3 Wise Interview.

4 http://notable_biographies.com/Ni-Pe/Noriega_Manuel.html.

5 Williams Interview.

6 Hanneman Interview.

7 Ibid.

8 Wise Interview.

9 Hanneman Interview.

10 The Life of James Brown, 183.

11 Williams Interview.

James Brown’s Favorite Uncle The Hal Neely Story Chapter Twenty-Nine

Lieber and Stoller, one-time partners of Hal Neely

Previously in the book: Nebraskan Hal Neely began his career touring with big bands and worked his way into Syd Nathan’s King records, producing rock and country songs. Along the way he worked with James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, who referred to Neely as his favorite uncle. Eventually he became one of the owners of Starday-King.

In the early 1970s, the record industry experienced a loss of sales which could not be reversed. Pierce said Neely’s course of action was to record larger bands with fuller arrangements which did not help the financial status of Starday-King.1 The Bienstocks saw a different problem with the business operation in Nashville.

“I was at the Gavin Convention,” Johnny Bienstock said, “and I saw this guy (Neely) having a lavish party and everything else. I said to Freddy, ‘Starday-King Records must be doing phenomenally.’ He was treating jockeys like I’ve never seen; he was having bigger parties than Atlantic Records. Freddy was furious.” It was at this time the Bienstocks began to consider extricating themselves from the record company, even if it meant taking a financial loss. They were still interested, however, in the company’s song publishing catalog.2

“For whatever reason,” Wilson said, “the Neely, Bienstock, Lieber-Stoller situation became not as close or as productive as it had been initially hoped for, and the relationship there became sort of, well, at loggerheads. They being in New York – that is, Lieber-Stoller and Bienstock – and Neely in Cincinnati or in Nashville. Internal paperwork problems went unsolved because the people who needed to make such decisions were never in the same place at the same time. Beinstock, Lieber and Stoller in New York could only see the financial statements of recording costs.” Wilson felt they weren’t being informed about the rationale behind the numbers.3

The company endured mounting recording costs which had not been recouped. “I just visualized a lot of problems that maybe could have been overcome, given a little reinvestment money to pull the thing along,” Wilson said. “But I would be answering, really, to some people who had not been in the other end of the record business.” Lieber-Stoller and Bienstock had been involved in A&R (artists and repertoire) and publishing. Wilson and Neely were in distribution and marketing. “I just felt at the time, and this later came to pass, that their main thrust, all of a sudden, was not to perpetuate a record company but was to divest themselves of the record company and only keep the publishing end, which was really what happened.”4

Even Neely’s good friend Williams said he made a few bad decisions on producing new performers. He said one demonstration tape sat on Neely’s desk for months. Others urged him to produce it but he did not because he thought it was just a so-so song. The song “I Never Promised You a Rose Garden” went on to be a big hit for another company.5

At one point Starday-King started selling off some of its real estate. Billboard Magazine reported in its Feb. 19, 1972 edition that Owepar, owned by Dolly Parton, Louis Owens and Porter Wagonner, bought Starday’s Townhouse building on Music Row to house its business activities.

In another effort to generate revenues, Starday-King released a second series of the Old King Gold catalogue, a collection of 31 rock ‘n’ roll and rhythm and blues singles from the 1950s, according to an article in Billboard Magazine in the Nov. 18, 1972 issue.

“What we did, originally, was to prepare a series of our King catalogue vintage tracks and turn them into pre-packaged sets which were sent to jukebox operators and one-stops,” Neely told Billboard. “Then all of a sudden we found we’re getting calls from underground college areas. This led us into our third pressing of the original series.” He said the company was planning to release a third in the series early the next year and eventually expanding to nine albums.

Business continued to decline, according to Pierce, and “after about a year and a half, the operation in Nashville was deeply in debt, and the Bienstock brothers came down and discontinued Hal Neely.”6

Eventually, Wilson said, Lieber, Stoller and Bienstock voted for Neely to resign as president, but Neely still owned one third of the Tennessee Recording Corporation.7

Neely gave a major interview with Billboard Magazine in its Oct. 6, 1973 edition. He said negotiations had lasted more than a week in both New York and Nashville over the Starday-King division of Tennessee Recording and Publishing Company. Neely told the magazine at first he was asked to resign. After Neely refused, the other three owners voted him off the board, while he retained his shares. The three men—Bienstock, treasurer; Lieber, secretary; and Stoller, board member—offered to purchase Neely’s percentage, and he countered with an offer to buy their shares.

“Neither offer was acceptable,” Neely said in the interview. “We were far apart at first, but we have been getting closer together. I am still hopeful of making the purchase.” He explained that the move began because Starday-King had not had a hit record for nine months. “I poured my own money into it, but there had been considerable disagreements over the way the firm should be run.”

Neely said if he were unable to buy out the other three, and they purchased his assets, he would immediately start another recording company and publishing firm. He owned a part of the physical properties and the existing catalogue through Neely Corporation Inc. (Review of Billboard files revealed Neely did not follow through with these plans.)

“If I should get out, I will be free and clear to enter business and compete.” Neely stressed he and the former partners were still “very friendly. It is now down to the point where the lawyers are involved for the most part, protecting their clients.” He said the company was still very healthy with the publishing company alone worth more than $1 million. He added that whatever debts existed were more than covered by the properties themselves.

Billboard reported that Bienstock said he would make a statement later in the week. (Likewise, a review of Billboard’s files showed Bienstock did not make any statement.) Lieber and Stoller were not available for comment. Neely concluded by saying if no agreement was reached that sale to a third party would take place.

The job of president was offered to Wilson, but he said, “I declined, because I could see the handwriting on the wall. And shortly after that period I resigned.” Wilson went on to work in the new distribution wing of Polygram, the parent company of Polydor which had bought James Brown’s contract.8

Don Pierce stayed on the Starday-King payroll for two years with an official title of advisor but actually took no role in the operation of the company. He bought a new home on the Old Hickory Lake, the same neighborhood where Neely lived. Over the years Pierce dabbled in real estate, automobile parts manufacturing, and established the Golden Eagle master achievement award for the country music industry.9

“Those guys (the Bienstocks) are only interested in the music publishing,” Pierce said. “That they won’t give up. They hold those copyrights and they know that those copyrights don’t argue. They just grow money. But they’re not in the record business. Take the records and get as much of it in the marketplace as possible. But we’ll do the publishing.”10

Looking around the music industry, the Bienstocks found a likely buyer in Gayron “Moe” Lytle, who with songwriter Tommy Hill founded Gusto Records in 1973. The company specialized in reissuing and licensing records from its catalog of acquired and self-produced music. 11

The Bienstocks originally wanted $500,000 for Starday and King masters and tapes in 1975. Pierce recalled Tommy Hill telling him, “Moe went up there, and laid down a check for $375,000. They (the Bienstocks) said, ‘You’re out of your mind.’”

Lytle picked up the check and said, “I’ll be at my hotel room.”

Hill said the Bienstocks discussed the proposition and decided that their business relationship with Neely was not working out right.

They didn’t have anywhere else to go,” Pierce said. “They didn’t know what to do with the masters. They don’t know a goddamn thing about records. They got all the songs but they needed someone to use those masters. So they took the $375,000. Imagine that! The whole King and Starday catalogs. Of course things were low ebb back then. They weren’t like they are now. It was just a different ballgame then.”12

In the deal, Gusto Records acquired thousands of master records and tapes which had been produced by King, Starday, and their subsidiaries. Included in the deal were all the record covers, photographs, promotional materials, contracts and other fan collectibles accumulated during the 30 years of running the companies. Lytle was quoted as saying he bought the masters because he wanted the Starday catalog and considered the King music just as an “add-on.” Gusto Records continued to own the King catalog which meant Lytle had now owned it longer than Syd Nathan.13

Master tapes generate immediate income upon the release to the public. They can become a source of quick and easy money but can also make it harder for a company to use its imagination and create new material. Gusto Records launched in 1978 a series of long-play records, cassettes, and eight-track tapes, which proved to be a treasure trove for fans and collectors. These records were affordable, plentiful, and easy to find.14

Tennessee Recording and Publishing, however, kept the publishing rights to thousands of songs on the King and Starday labels because this was considered to be much more profitable. Among the hit songs owned by the labels were “Fever,” “Dedicated to the One I Love,” “Please, Please, Please,” and “Work with Me, Annie.”15

During this same time Neely sold his interest in Tennessee Recording and Publishing Company to Beinstock, Lieber and Stoller. In his memoirs, Neely claimed who would sell out to whom was determined by a coin toss which he said he lost. Both Mike Stoller and business associates of the late Freddy Bienstock disagree with this story.

“I’m not quite certain what Hal Neely meant by a coin toss,” Stoller said. “With that image in mind, what did each of the heads and tails represent? My memory of the reason for the sale of the King and Starday Record catalogs to Moe Lytle was that Hal had spent a great deal more money (including his own compensation) than the company was earning. That resulted in the debts far outweighing the receipts of the company. Included among the expenses that Hal incurred was the purchase of a new bus for a recording artist who had had one successful recording. In regard to the sale, as I recall, the phrase ‘25 cents on the dollar’ was bandied about.”16

Bob Golden, vice president of marketing for Carlin America, Inc. — which was founded and run by Freddy Bienstock until his death in 2009–said he believed Mr. Neely’s memories of this transaction were probably inaccurate.

“I can verify that Freddy always considered and treated everyone in any business relationship he had as a colleague. He took great pride in the fact that all his dealings were scrupulously fair and square in a particularly hard and tough business.”17

Over a short period of time all employees of what had been Starday-King were dismissed, according to Wilson. “About the only operation that continued to exist until such time that Gusto Records bought the masters of Starday-King, about the only thing that continued to operate was the mail order operation, Cindy Lou’s Mail Order,” Wilson said. “Or as it used to be known, the Country Music Record Club.”18

“Hal never recovered from the Lieber-Stoller deal,” Wise said. “He never recovered in business. Hal was always the eternal optimist, but this was the beginning of the end.”19

Williams believed Neely sold Starday-King because he saw that major record companies, such as RCA and Capitol, were moving into Nashville and would put independents out of business. “He was right and wrong. The majors took over for a while but finally found it more feasible to let independents produce records instead.” 20