You may remember the news reports surrounding the death of best-selling novelist Irving Stone in 1989. He was found slumped over his desk, dead from an apparent heart attack, with his hand still holding a pen as though he were in the middle of a letter. On the paper he had scrawled, “My Dear Friend”.

Literary authorities debated for months who this dear friend was and why had Stone had only one other word written on the page before he died and what was the meaning behind it. Irving has been gone several years now and I myself am an old man, so I think it is safe to reveal that I was his dear friend.

It was late 1978, and I was flying to Virginia to join my wife and son at my in-laws’ house for Christmas. I looked forward neither to the flight nor the visit. I didn’t know to be afraid I might die in a plane crash, or to fear surviving the flight and have to endure my wife’s parents for two long, cold weeks. The last thing I needed was a grumpy old man plopping in the seat next to me and start mumbling to himself. His comments became louder and unfortunately more distinct. When he got to the part about how it was intolerable that first class was filled to capacity, I could no longer contain myself.

“Well, I’ll try not to breathe on you.”

One of my worst character flaws was opening my mouth and letting fly words that I wish I could immediately grab and cram back in. Not only was I subjected to a disgruntled aristocrat generally angry at the airline for not accommodating him but also was going to be the personal object of his disdain for the next three hours. Glancing over at him, I watched his face change from shock, anger and incredulity to surprise, humor and relaxation. He laughed out loud for about half a minute, which in a crowded tourist class airplane section was exceptionally long. Several fellow travelers turned to see what was going on.

“This is the first time I’ve laughed in at least three days,” he said. “Thank you.”

“You’re welcome.”

Smiling, he stared at me, which made me uncomfortable. I decided I would have preferred to have him angry and ignoring me in excess than have all this attention.

“You don’t know who I am, do you?”

My first impulse was to ask, “And why should I care?” Instead I restrained myself. “I take it you are a person who prefers to fly first class.”

He chuckled again. “And why should you care in the first place?” Settling into his cramped seat, the man looked straight ahead. “I apologize for being an insufferable bore. I assume everyone knows who I am and will try to convince me he has written the next best-selling novel in the world if only he could get a foot in the door.”

I had written a novel and sent the first three chapters to Doubleday. An editor replied he liked them and wanted to see the rest of it. By the time I mailed it, he retired and the next editor didn’t like it at all. Since I didn’t want to add another rejection to my list of achievements, I refrained from telling the author my story.

“You don’t have a novel, do you?”

“Oh, no,” I lied. “Used to work for newspapers though. But that’s not real writing, is it?”

“All writing is real writing. I admire how you people can write a full story, zip like that and have it published the next day. I could never do that.”

“It’s called a deadline. And the necessity of being paid.”

He laughed again. “None of the reporters I’ve talked to have ever made me laugh. Why is that?”

“The deadline.” I paused. “I interviewed a famous author once. One of the Haileys. Not the one who wrote Roots but the other one. You know. Hotel. Airport.”

“Yes, I do know him.”

“He acted like he was a character in one of his own novels.”

The man giggled.

“And he looks like he has a personal tanning bed in his house and uses it daily.”

“He does, he does.”

Three hours passed quickly as I tossed out random comments about writing and writers while the man laughed all through it. I never felt so clever in my life. By the time we were circling the airport, he pulled out a note pad and pen.

“Please put your initials and address on this,” he said. “I would like to hear from you. But I think it would be better if we kept our identities to initials. It would ruin it, don’t you think, if you knew exactly who I was.”

It was just as well. I didn’t think I wanted to be on first name basis when anyone that eccentric anyway. By the first week of the new year I received a handsome letter on personalized stationary. At the top of the paper were the initials “IRS”. He apologized again for his rudeness on the plane and reiterated how much he had enjoyed our conversation.

“By the way, I was at Hailey’s house for New Year’s Eve and giggled at him the entire evening. He was quite put out by it and asked what the matter was. I couldn’t tell him that he was acting like a character in one of his novels, so I just said I had had too much wine. Please keep me informed about what you are reading. I don’t get honest opinions often.”

This put me in a rather odd situation because I was going through a period when I wasn’t reading much of anything. The last novel I had picked up I hadn’t even finished.

“I tried to read Irving Stone’s book about Sigmund Freund, Passions of the Mind, but couldn’t finish it. I supposed it was over my head. I can’t read William Faulkner either.”

In the return mail I received this note from IRS:

“I agree about William Faulkner. He tried to be the American William Shakespeare. Stone was just lucky. He needs to remember to be appreciative of what he has been given.”

At the time I thought he was bit rough on Stone, but since he knew all these people personally I didn’t want to dispute his opinion. Through the years we corresponded, and I resisted the temptation to talk about my own writing. I wrote a few more novels, some plays and screenplays, none of them getting past the standard rejection slip. Every now and then I did pump him for gossip. For example, I asked if he thought Ernest Hemingway actually committed suicide or was it murder.

“Hemingway was crazy,” IRS wrote. “He could have been a great writer if he wasn’t always trying to prove he was a real man, whatever a real man is.”

By the middle of 1989 I had a huge stack of handwritten letters from the anonymous novelist. In September not one single letter came in the mail. Perhaps he had grown tired of connecting with a common man. On October first, however, I received this:

“My dear friend, I am sorry I have not written lately. My health is beginning to fail. Not to bore you with details but I’ve been hospitalized for the last month. I fear I have written my last novel, which is a shame since it’s all I’ve done for the last fifty years. Once again I feel remorse over our relationship. I regret having taken advantage of your good nature and humor. In the ten years we have corresponded I should have dropped my self-defense mechanism to reach out to help you with whatever dreams you have. To make up for it, I want you to feel free to ask me for one favor. No matter what it is, I will do everything within my power to grant it.”

This put me in a particular bind. While my heart raced a bit with the prospect of finally being published by a real publisher, I didn’t want to ruin the good feelings of our ten-year relationship by having him try to sell my books and fail. However, I’ve always felt it was bad manners to reject someone’s offer to do me a favor, so I wrote back this:

“My dear friend, Corresponding with you for ten years has been an honor and a pleasure, I think, made even more special by the anonymity. Therefore, my only request is that you share with me what your middle name is. That way you can keep your privacy and I can have the joy of knowing a private fact about a public person.”

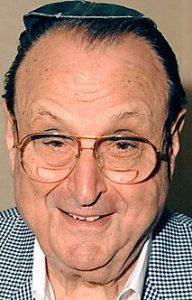

Another month passed without a letter. Again I assumed I had presumed too much and lost this special relationship. The next morning I read the local newspaper. Irving Stone, author of bestsellers Lust for Life, Agony and the Ecstasy and Passions of the Mind, died at his home, leaving an enigma—an unfinished letter to “my dear friend.” I smiled when I read the only word on the letter.

“Rebecca.”

(Author’s note: I don’t know why I feel compelled to add this clarification since as a short story it’s obviously fiction and therefore not true. Anyway, for the record, Irving Stone’s middle initial was I and not Rebecca. I don’t know what it was but I’m sure it was something serious and dignified, like Irene.)

Oh how funny. I bought in to this story hook, line and sinker. All through I believed this to be a true story Surprised you had never told this before. LOL. Imagine my surprise that it is fiction and I am such a gullible soul. I enjoy your writing. Your humor is a delight