(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school and his brother Tad was nicer. A black family moved into the barn to help them pick the cotton. Mama continued to have dizzy spells.)

“Mrs. Johnson says she knows all kinds of medicine to make you feel better,” Herman offered. He became nervous when his parents talked about how they couldn’t afford to go to the doctor when they felt sick.

Mama laughed. “I’m sure she does.”

“Don’t call her Mrs. Johnson,” Papa instructed.

“Why? What do I call her?”

“Call her Josie. That’s her name,” Mama replied. Her attention now was on the potatoes.

“Or the Johnson woman,” Papa instructed.

“Why? Isn’t she Mrs. Johnson?” Herman pushed.

Papa raised his eyebrows. “We don’t know if they’re married or not.”

“But they have children.”

“Oh, that doesn’t mean anything.” Mama laughed again.

“But—“

Papa interrupted sternly. “Now that’s enough of that. Stay out of the barn. Don’t call her Mrs. Johnson. Don’t ask why. Just do it.”

Mama shook her head. “Herman’s always full of questions.”

Herman stared at the floor. “Yes, Papa.” Then he went up to the loft so he could be alone with his bear family.

“I don’t think Mama and Papa are very nice about the Johnsons,” he confided to Burly and his parents.

“But your mama and papa are very nice to you,” Burly reminded him. “Don’t ever forget that.”

“Burly’s right,” Pearly Bear added. “Their love for all three of you children fills this house and makes it warm.”

“But that doesn’t mean you should pretend they’re nice to the Johnsons,” Burly Senior interjected. “Sometimes even parents can be wrong.”

“Even you?” Burly asked.

Burly Senior shuffled his burlap body a bit and cleared his throat. “Well, I haven’t been around long enough to make any mistakes. But I imagine I will, some day.”

Pearly giggled at her husband, and soon all four of them were having a good laugh.

The next day out in the field Herman sat next to Mrs. Johnson during lunch even though Tad gave him an angry look. Herman ignored his brother and looked at a nearby tree.

“Those birds sure are singing pretty,” he said, munching on a sandwich.

Mrs. Johnson quickly swallowed a mouthful of food and waved her hand at the tree. “Oh, those are turtledoves. They’ve got a beautiful song to sing all right, but you better not let one get in your house.”

“Why not?” Herman asked.

“Lord sakes alive, baby,” Mrs. Johnson exclaimed. “You let a turtledove in your house, and it starts to cooing and such, and sure enough somebody in your family will wind up dead.”

Tad snorted in disbelief. Herman couldn’t help but notice the three Johnson boys glowering at Tad. He also noticed they put their hands up to their face as they whispered to each other. One of them laughed but the other two hit him on his shoulder.

“Now, Josie,” her husband said in a reproving tone, “you know you shouldn’t be telling your stories to those boys.”

Before she could reply, Herman’s father walked up and announced, “Time to get back to work.”

Herman and Tad picked cotton side by side.

“You don’t believe that malarkey about turtledoves, do you?” Tad asked.

“N-no, I guess not,” Herman stammered. He really didn’t know what to believe but he thought it would be safer to say no to Tad.

“That’s why you shouldn’t talk to coloreds.” Tad used his I-told-you-so voice.

“You kids! Get to work!” Papa shouted, and that was the end of that.

When they were finished for the day and had emptied their sacks into a big wagon with tall chicken wire walls, Tad pulled Herman over to the side.

“Come on with me,” he whispered. “We’re going to have some fun.”

Herman smiled and ran along with him. It wasn’t often that Tad included him in his fun. Tad grabbed a burlap bag from the side of the barn and towed Herman down the road to the tree where the turtledoves were singing at noon. They carefully climbed the branches until they came to a nest. Tad threw his bag over the nest, capturing a turtledove.

“What are you going to do with it?” Herman asked.

Tad winked. “You’ll see.”

When they climbed down the tree there stood their father with his arms folded across his chest.

“And what do you boys think you’re up to?” Herman recognized that voice. That was the voice Papa used before the spanking began.

“I don’t know; just having fun,” Herman whispered.

“How about you, Tad?”

Tad tried to hide the sack behind him. “Aww, Papa, it was just a little joke. We were going to put the turtledove in the barn to scare the Johnsons.”

“Drop it! Right now! Herman, you go into the house. Tad! You follow me!”

Tad and his father marched around to the far side of the barn. When Herman got in the house he looked out the window to see what was going on. He could hear the whacks all the way to the house. Just then, the youngest of the Johnson boys ran out of the barn and into the woods. He turned to his mother and Callie who were cutting up vegetables for a stew.

“Papa’s beating Tad again.”

“What on earth for?” She dried her wet hands on her apron.

Herman explained how Mrs. Johnson told them about the turtledove curse and about how Tad was going to catch a turtledove and put it in the barn to scare the Johnsons. They had one in a sack when Papa came up and stopped the whole thing.

“Woody’s going to kill that boy before he makes it to manhood. Well, I could use that turtledove in the stew. Where is it?”

“In the woods,” Herman replied.

“Come take me to it.”

“Oh, I want to go with you too!” Callie pleaded. “This is the most fun I’ve had in a long time!”

When they arrive at the tree where the turtledove nest was, they found the burlap bag but it was empty.

“It must have worked its way out. Oh well, we tried.” Mama took a step but stopped to bend over. “There’s that dizziness again.” She lifted her head to smile at Herman. “Did anything else happen today?”

“After Papa took Tad out behind the barn, one of the Johnson boys ran into the woods,” Herman replied.

“Maybe he went to get the turtledove,” Callie offered.

“Why on earth would he do that? And how did he know there was a turtledove in a bag out there?”

“Maybe he overheard Papa and Tad talking out behind the barn.” Callie wringed her hands, looking down.

“No, they wouldn’t do that,” Mama said, shaking her head.

“Why not?” Herman asked.

“You ask too many questions, Herman. Stop it,” she ordered. “Let’s get back to the house. Woody and Tad must be there by now.”

When they entered the house, Tad and his father were looking up in the rafters. A turtle dove was cooing.

“What on earth is that noise?” Callie asked.

“Oh, somehow a turtledove got in the house,” their father said. “Don’t worry. I’ll get it. Maybe your mama can put it in the stew.”

“Tad!” His mother glared at him. “Did you bring that bird into my house?”

“No!” Tad looked frustrated. “I didn’t. Honest.”

The bird continued cooing, flitting away every time their father got near.

“The cooing is pretty, but it’s getting on my nerves,” Callie said.

“You’re not the only one,” her mother murmured.

Herman watched mama closely. It looked to him like she must be getting dizzy again. “Mama, are you all right?”

“Of course, I am, baby. It’s just that….” Their mother’s voice trailed off as she fell to the floor.

“Papa! Mama’s fainted!” Herman yelled.

His father jumped down from the rafters, swooped his wife up into his arms and rushed her into their bedroom. Callie ran in after them and closed the door. Herman and Tad stared at each other for what seemed like hours. In a few minutes Callie came out crying. She slumped into one of the kitchen table chairs and sobbed uncontrollably. Her brothers approached her slowly, as though they were treading on holy ground.

“What’s wrong?” Tad whispered.

Callie looked up, tears streaming down her cheeks and her eyes puffy and red. She could hardly get the words out.

“Mama’s dead.”

Herman and Tad were stunned. They couldn’t move. They couldn’t speak. They couldn’t think. Slowly Herman’s eyes focused on the shadows of the rafters. The turtledove was gently cooing.

Category Archives: Novels

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty-Two

Joachim Von Ribbentrop

Previously in the novel: A mysterious man in black foils novice mercenary Leon from kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer. Wallis, in quick succession, dumps first husband Winfield, kills Uncle Sol and marries Ernest.And throws in an affair with German Von Ribbentrop.

The next few days were quite a whirlwind adventure for Wallis. Joachim von Ribbentrop, besides owning an international champagne enterprise, was a member of a highly prestigious military family. And just for fun he was a great tennis player. When he played Wallis on a Paris court, he found her to be an exhilarating opponent.

“My dear, you play tennis like a man,” Von Ribbentrop complimented her after he won a very close match.

“I’ve been told I do many things like a man.”

They immediately adjourned to the club house for a cold drink.

“And you speak English like you were born in London,” she observed, sipping her champagne and reaching for a basket of crackers. Leaning back, she eyed him over the rim of her glass. “You use your tongue and lips very well.”

“When you sell champagne around the world you have to learn many languages.”

“I’ve learned if you flash enough money around people, they learn to speak English pretty fast.”

“Ah, but you see I am trying to get them to flash their money. That requires a certain amount of finesse.”

“That’s fine for you but I’ve never had to sell anything in my life.”

“But that’s not true, my dear Wallis. You are the most expert salesman I have ever met. In fact, you are trying to sell me on doing something for you right now.”

Wallis waved at the waiter for another glass of champagne, crunched on a cracker and then lit a cigarette, blowing the smoke out of the corner of her slim slit of a mouth.

“If truth be told, I am in pique. My uncle changed his will. Originally the five million was going to be mine but now it will establish a home for indigent dowagers, whatever the hell that is.”

Von Ribbentrop leaned forward. “Do you want your uncle forced to change the will back to you and then have him killed? It can be done. I have access to an elite group of assassins.”

“Oh really?” Wallis stopped puffing on her cigarette and raised a brow.

“My family has a long history of flirting with the dark side of humanity. I had an uncle, Heinrich, who married one of the Romanov cousins. He got a tip from the organization that someone was out to assassinate her. So he moved them to the Bahamas, thinking they would never find them there. Well, they did but instead of taking her out they took him out instead. The newspapers said it was a heart attack but the family knew what happened. My aunt disappeared somewhere out in the American West. Even the organization doesn’t try anything among the cactus and rattlesnakes.”

Wallis fluttered her eyes. “Well, now you have my attention. And who might run this organization?”

“If I tell you I’ll have to kill you.” He reclined in his cushioned chair and smiled.

Wallis grunted a laugh. “You’d be surprised how many times I’ve heard that one before.” She shrugged it off. “No, the old bastard’s dead already. What I need is a good lawyer to contest the will.”

“I can help with that too.” He grinned rakishly and reached for the bud vase on the table. Von Ribbentrop lifted a white carnation from the vase and handed it to Wallis. “White carnations are for remembrance. Now what could you do for me that you could remember fondly by looking at a white carnation?”

Taking the flower, she crumpled it in her right fist. “I can do all sorts of things with my hands.”

Von Ribbentrop stood and extended his arm to her. Wallis took it, and he guided her to his hotel suite. The next morning when she left, he handed her a business card for Virginia State Senator Aubrey Weaver.

“He’s the best man I know in the United States for contesting wills and marriages.” He emphasized the word marriages with a wink.

Good luck with that one, Wallis thought. She had no room for a German on her future husband list. At least he was easily satisfied sexually. Back in the states, she deposited Bessie in Baltimore and stopped over in Richmond to confer with Aubrey Weaver. Wallis went through three cigarettes explaining the situation. After listening to her case against Uncle Sol, the senator shook his head.

“I’m sure I could do something to have the will overturned. It seems his health was declining and an argument could be proffered he made the changes in a state of unsound mind. These things can linger in court for years. Most of the money, I assume, was in stocks and my sources on Wall Street tell me the overheated market is going to pop sometime in the next year.” He shrugged. “What’s left of your Uncle Sol’s money after that may not be worth the bother.”

Wallis crushed out her butt in a dirty tray on the lawyer’s desk. “It’s always worth the bother. I don’t care if it’s fifty dollars, I want it.”

Weaver smiled. “Remind me never to be on your bad side.”

“I’m going to need a divorce soon. I’m told you’re good at those things.”

“Yes, little lady, I am.”

The next morning Wallis was on the train to Warrenton in the Blue Ridge Mountains to resume her active social life among the young wealthy elite. Just a few days later she was playing a round of golf with her buddies when she missed an easy putt. One of the women—whose name Wallis had not caught—laughed merrily.

“Well you know what they say. It always isn’t a win-win situation. Sometimes it’s a lose-win situation.”

Wallis was back in Weaver’s office within a week or two and hoped for better news than he had given about Uncle Sol’s will.

“Now, it is absolutely necessary here in Virginia to prove you and your husband have not been in close physical proximity of each other in three years.”

“We met for a few moments a couple of times so he could give me money,” she replied. “Will that be a problem?”

“I don’t think so if your husband won’t mind making a slightly dishonest statement to the court,” Weaver replied. “Do you think he would risk perjuring himself?”

“My dear Sen. Weaver, I thought I had made it perfectly clear both my husband and I have been blessed with a total absence of scruples.”

Submitted to Fauquier County Court in December of 1928 was this letter from Winfield Spencer:

“I have come to the definite conclusion that I can never live with you again. During the past three years, since I have been away from you, I have been happier than ever before.”

The court fell for it, and Wallis was relieved to receive her divorce decree. She said good-bye to her social circle in Warrenton and moved into her mother’s Washington home where she proceeded to make a spectacle of herself by flirting with as many eligible bachelors as possible. This masked her intentions to marry Ernest as soon as his divorce became finalized.

In the spring of 1929 she read in the social column of a New York newspaper that the popular Simpsons had divorced.

“Quelle domage,” the columnist quipped, “but c’est la vie. We hope Ernest will be in high spirits for the summer social season.”

Ernest was not only in high spirits by July but also celebrating his marriage to Wallis. The only let-down for the New York set was that the nuptials occurred in the Chelsea Registry Office in London early one morning. They hosted a champagne brunch for their English friends, then motored to the coast where they sailed for France. Wallis and Ernest had a swell time dining, drinking and shopping in Paris upon their arrival in the late afternoon.

By the end of the long exhausting celebration, actually about four a.m. the next day, Wallis faced a serious decision. Was she going to drug Ernest for her big reveal or take her chances with him not being under the influence nor chained to the bed. She decided her new husband was of a different temperament than Win. Nothing ever seemed to faze him. She had never witnessed him angry, even on the mildest level.

Ernest, already totally nude, brought two glasses of champagne to bed. Wallis took her drink and slammed it back.

“Do you know what I like best about you, Ernest?”

He chuckled as he drank his champagne. “My father’s money.”

“Your devil may care attitude. Nothing ever shocks you.”

“Oh. Yes. That’s true too.”

Without another word, Wallis removed her nightgown. Ernest barely batted an eye and smiled.

“Well, there are many, many ways to have a good time.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Forty-Six

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Edwin Stanton holds President and Mrs. Lincoln captive under guard in basement of the White House. Janitor Gabby Zook by accident must stay in the basement too. Guard Adam Christy tells the Lincoln Tad has become ill. Lincoln demands the boy be brought to them.

“Oh, I’m so excited,” Tad said with a bit of a giggle. “I bet Mama’s going to cry.”

“Of course she’ll cry.” Alethia hugged him. “I’m about to cry just thinking about it. Enjoy every minute of it.”

“You can come with me,” Tad offered as he sat up.

“I don’t think that would be a good idea.” Alethia cast a worried glance toward Adam. “You see, um, the fewer people going downstairs, the better. We don’t want a grand parade to the basement, do we?”

“I guess not.” Tad lowered his head in disappointment. He looked up at Adam. “We better go now.”

Bending over to pick up Tad, Adam was surprised by how light the boy was. Hardly any meat on his bones, he thought, just like me when I was that age. He held the child close to him.

“I’ll open the door for you.” Alethia pulled on the knob. “Wait a minute.” She peeked out and looked both ways down the long, dark hallway, barely lit by flickering gas lamps. “Tom Pen makes his rounds soon to put out the lights.” She smiled at Adam. “It’s clear.”

Tad lifted his head, which he had snuggled into Adam’s shoulder, and smiled, waving his hand. “See you later.”

“Yes, see you later, my darling.”

Adam quickly crossed the hall to the service stairs, where he opened the door, looked back to see Alethia smiling through the crack of Tad’s bedroom door, and then shut it and started down the straw-matted steps with the sickly, perspiration-drenched boy, scented by medicines and faint traces of urine, who snuggled and moaned.

“You’re much nicer than I first thought,” Tad murmured, not lifting his face but nuzzling in deeper. “You don’t have to be a lieutenant.”

“Thank you.”

“Where did Papa find you?”

“Mr. Stanton recommended me,” Adam replied after an awkward pause. “He’s from my hometown.”

“Oh.” Tad wiped his running nose on Adam’s rumpled blue tunic. “I don’t like Mr. Stanton. He’s mean.”

“He’s…” Adam stumbled over his words, trying to find the right one to describe the secretary of war. “He’s professional.”

“I don’t know what that means.” He turned his nose into Adam’s armpit. “You smell like you ain’t had a bath in a week.”

“Oh.”

“That’s all right. I hate baths too.”

“Do you want me to tell you what professional means?” Adam stopped at the basement door.

“No. It probably means he’s mean but got a good reason to be.”

“Close enough.”

Adam opened the door and searched the vaulted basement hall. Finding no one around, he quickly entered, closed the door, and hastened his pace to the billiards room. Suddenly Phebe stepped from her room, fixed Adam in her gaze, and crossed her arms. Like a deer trapped by a poised hunter, he said nothing, did nothing, except to let his chin droop.

“Hello, Phebe,” Tad said, with a chirp as he lifted his head and smiled. “I gotta go puke.”

“You don’t get sick in your room?” Her eyes widened.

“Stinks up the place, Mama says,” he replied. “’Course, sometimes I don’t know it’s comin’ up until it’s too late. One time I got vomit over one of Mama’s fancy dresses. Boy, did she get mad.”

“I can imagine,” Phebe said.

“Vomit won’t hurt a uniform much,” Tad informed her.

“So, Private Christy. You’ve been given puke patrol.”

“Puke patrol.” Tad laughed. “That’s funny.”

“Yes,” Adam replied with a tight smile, “so if you’ll excuse us, we’ve serious regurgitation business to tend to.”

Phebe shook her head and waved them on, as she went back to her room.

“Reach down in my pocket and get the keys.”

“All right.” Tad retrieved them. “Here they are.”

As Adam opened the door and carried Tad through, he noticed Phebe’s door across the hall. It was slightly ajar. That might be a point of concern, but Adam dismissed it as he presented the boy to his parents.

“Oh, my Taddie! Oh, my baby! Oh, my baby!” Mrs. Lincoln grabbed her son from Adam, and immediately dropped to the floor, sobbing and clutching him to her bosom.

“See, I told you she’d cry,” Tad said, his voice muffled.

“Thank you.” Lincoln walked up and put a large hand on Adam’s shoulder.

“You’re welcome, Mr. President.”

“I’m sorry I grabbed you. I should have never lost control.”

“I understand, Mr. President.”

“Have you had subnitrate of bismuth?” Mrs. Lincoln held Tad’s face in her hands.

“It tastes awful.”

“But it made you feel better, didn’t it?”

“Yes, Mama.”

“I suppose that woman isn’t completely incompetent.” Mrs. Lincoln held his head close to her breast.

“Oh no. She’s a nice lady,” Tad said, pulling away to look at his mother. “She looks just like you.” He smiled. “’Course, I knew the very first day.”

“You did? How bright of you,” Lincoln said, kneeling down to his wife and son. “And how did you figure that out so fast?”

“She doesn’t get mad like you do, Mama.”

“Tad!” Mrs. Lincoln’s mouth flew open. She looked at her husband. “Mr. Lincoln!”

Lincoln tried to be serious, but began to smile, which gave way to a chuckle. Mrs. Lincoln slapped at him, but could not help but join him. Tad, happy he had made his parents happy, giggled.

Adam smiled until he glanced over at the boxes and crates to see Gabby with his homemade quilt clutched tightly around his shoulders, and remembered this was not a happy ending, but merely a respite in their ordeal.

Burly Chapter Ten

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. Herman asked his parents to make burlap bears for his brother and sister for Christmas. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school, Tad was nicer and the tent show was coming to town. Herman liked it, but didn’t know why black people had to sit behind a rope.)

Burly Senior’s questions—were bears and people much different why black people were not treated honestly–bothered Herman all that summer as he worked in the cotton field alongside his father, Tad and Callie. He didn’t dare mention black people to papa for fear he would look like he smelled rotten eggs again. One day, as they hoed weeds around from the leafy green plants, Herman gathered his courage and asked Tad.

“What do you mean, why do black people have to sit in the back behind a rope?” Tad snapped. “You don’t want to sit next to some big fat old colored woman, would you? She might touch you.”

Herman’s eyes widened. “Does it rub off?

Tad spat and hoed faster. “Don’t be stupid.”

Callie, who was in the next row, glared at Tad. “Don’t call Herman stupid.”

“I’ll call him anything I want!” Tad yelled.

“You’re the stupid one!” Callie retorted.

Papa walked up with his hoe, and the argument stopped. A few minutes went by and then Callie looked round and whispered to Herman.

“What was all that about anyway?”

“Aww, I asked if the black rubs off on you if a colored person touched you.”

Callie stifled a giggle. “Of course not. That is stupid.” She paused and added quickly. “But it was wrong for Tad to call you stupid.”

They hoed side by side for about an hour before Herman had the courage to ask her the main question. “Callie, just why do black people have to sit in the back behind a rope?”

“We sat as far back as they did,” she replied without looking at her brother.

“But we came late and we didn’t have to sit behind a rope, like we were different.” When she didn’t say anything, Herman added in a whisper, “Are they different?”

Again Callie studiously kept her eyes to the ground. “Papa says they are.”

“Is—is papa right?”

First giving a quick glance to her father, Callie answered, “I don’t think so. But don’t say that to papa. He might get mad.”

Herman was confused. “Why? Doesn’t he want us to be honest? Wouldn’t it be better for everyone if we were honest?”

“Yes.” She hoed hard and fast. “But papa doesn’t think so. Maybe someday things will change.”

“But if papa thinks they’re different, maybe they are,” Herman thought aloud.

“Less talk! More work!” papa barked.

Herman didn’t ask any more questions, but he was terribly confused. He didn’t understand why Callie would believe different than papa or Tad. Maybe it was mama who believed differently, and Callie got it from her. That evening, after the hoeing was done, and Tad had gone swimming in the creek and Callie took Pearly Bear to play dolls with her friends, Herman went into the house and walked up to his mother who was chopping vegetables for a stew.

“Mama?”

His mother sighed but answered sweetly, “Yes, dear?”

“Are black people different?”

She stopped and looked down at him, her slender hands going to the nape of her neck to massage it. “What makes you ask a thing like that?”

Herman looked down. “I was just wondering.”

“Yes. Don’t worry about it,” she answered and went back to her chopping.

“But—why?” He was about to say Callie thought differently but stopped because he didn’t want to get her in trouble.

Mama laughed. “You think more than any one child I’ve ever seen.”

“But—“

Interrupting him firmly she said, “Go to the loft and play.”

Herman did as he was told, climbed the ladder and crawled into the bed to snuggle with Burly.

“Of course Callie is right,” Bear Senior announced. “People are people, no matter what color they are. Just like bears are bears, whether they’re made of burlap or some fancy material from Sears and Roebuck.”

“I even think bears and people are alike,” Burly offered.

“That’s right, son,” his Burly Senior agreed.

“But how could Callie know this and not papa, mama or Tad?” The more they talked, the more confused Herman became.

“Why do you know it?” Burly asked.

“I don’t know if I know it or not.” Herman hung his head.

“Of course you do,” Burly Senior told him.

Herman pulled them into his arms. “I guess I know because of all you.”

“No,” Burly said. “You knew before you even talked to us. You knew because it bothered you to see the black people roped off.”

“But you helped,” Herman offered.

“Of course,” Burly quipped with a smile. “That’s what we’re here for.”

Herman sighed. The whole situation was too much for him to understand. “I’m glad you talk to me.” He looked at Burly Senior. “Don’t you talk to Tad?”

“I would if he wanted me to,” the papa bear replied.

The summer continued, and Herman kept his thoughts about honesty to himself. Even though it was hard work, keeping the cotton rows clear of weeds and nice and soft for the plants to grow big and strong, he rather enjoyed it. This was the first year papa decided he was old enough to help, and Herman could feel himself grow taller every time Papa walked by, patted him on the back and said, “Good work.”

Eventually the hot, clear skies gave way to the clouds of fall, and school came back. This time Herman was not as scared. For one thing, the session had hardly begun when all the farm children were allowed to leave so they could pick cotton before bolls rotted on the branches. To pick them quickly was so important that papa actually paid a family to help pick the cotton.

The Johnsons were black, and Herman was happy papa had given them work for they looked very poor. Mr. Johnson was gray and stoop-shouldered. Mrs. Johnston was short and very stout, but also very talkative and friendly. They had three children, all boys and all older than Herman. They were distant and brooding. Herman liked to sit next to Mrs. Johnson when they stopped for lunch. She sang songs and told stories. Sometimes she would take his fingers and sing a little tune while wriggling each one.

“Don’t let her do that,” Tad scolded him as they went back to work in the rows of cotton.

“Do what?” Herman was puzzled.

“Touch you like that,” Tad replied in a hissing, whispery voice, glancing over his shoulder at the black family.

Herman laughed a little. “All she did was wiggle my fingers.”

“All she wants is to be able to touch a white person.

“Why should she want to do that?”

Tad looked at Herman with scorn. “Stupid. Don’t you know that’s what all blacks want to do?”

“Touch white people?” Herman couldn’t believe what Tad was saying.

“You just watch it.” Tad skulked away.

That night mother asked Herman to find his father quickly. She was sitting in one of the straight-backed wooden chairs with her head between her knees. That scared Herman, so he ran out to the barn, where he usually found his father. Instead he found the Johnsons bedding down in an empty stall.

“Well, hello, little fellow!” Mrs. Johnson said cheerfully.

“Have you seen my papa?” Herman’s voice was all tight from fear.

Mrs. Johnson frowned with concern. “What’s the matter, baby?”

Herman,” papa said from the barn door. “Come here.”

Herman ran to his father to tell him that mama wanted him, but before he could say anything, his father pulled him away.

“I thought I told you to stay out of the barn while we have them sleeping in there,” he lectured harshly. He emphasized the word “them” with a nastiness that made Herman uncomfortable.

“But mama, she’s not feeling good,” Herman whined. “She wanted me to find you.”

Papa straightened and stared at the house.

“Oh.”

He walked quickly to the door. Inside mama was already back at the kitchen peeling potatoes.

“Opal, are you all right?” Papa asked so sweetly than Herman didn’t feel uncomfortable anymore.

“Oh, I was just a little dizzy, that’s all.” She laughed, but it soon turned into a cough.” She turned to smile at Herman. “Thank you for getting your father so fast, Herman.”

Papa put his long, wormy arms around her. “Are you sure?”

She leaned against him. “No, I was just being silly.”

“I think I ought to take you to the doctor,” he said softly.

Mama turned to her work at the sink. “What would we pay him with?”

“We’ll have money when the cotton is sold,” papa replied.

“We need that money for more important things.” Mama was always practical.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty-One

Previously in the novel: A mysterious man in black foils novice mercenary Leon from kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Also in the world of espionage is socialite Wallis Spencer.

By the summer of 1928 Wallis was planning another trip to Europe with Aunt Bessie. She loved traveling with her mother’s spinster sister. Bessie wasn’t pretty, witty or judgmental. She had her head in the clouds. What better companion could a young woman want? Before the departure, she told her aunt she had to return to Warrenton to maintain her Virginia residency so she could finally escape the horrors of marriage to aviator Winfield Spencer.

Her actual destination was the old homestead in Baltimore where Uncle Sol, according to rumor, was on his death bed. This was her last chance to exact revenge for the horrible deeds he had inflicted upon her when she was a little girl.

Wallis lingered out on the street until she saw the nurse leave Sol’s house. Looking around the empty neighborhood she picked the lock to the front door and slipped inside. She crept upstairs to her uncle’s bedroom. When she entered she saw him swallowed up by sheets and blankets.

“Uncle Sollie, so glad to see you’re alive.”

Sol’s eyes fluttered open. When they focused on his visitor and he recognized his niece, they widened in fear. He quickly moved a pillow to his crotch.

“Bessiewallis, no. Please, no.”

She sat on the edge of the bed. “Besides hearing you were dying, I also heard the nasty gossip that you had changed your will. Instead of leaving your millions to me, you decided to create a home for destitute ladies in memory of that wicked mother of yours.”

Sol’s lips quivered. “But you have so much money now. I didn’t think you would mind.” He stopped short when he saw Wallis pull a long hat pin from her stylish black lacquered straw hat with a white satin ribbon around the crown.

“That wicked woman did not approve of my father. She didn’t even attend his funeral. Of course, I hadn’t even been born then but Aunt Bessie told me.”

“Bessie was wrong. Mother was there.”

“Now, now, that’s no way to talk about Aunt Bessie. She may be as dumb as a cow, but she does pay attention when it comes to who attends a funeral and who doesn’t.” Wallis removed the pillow from between his legs and leaned in with the hat pin.

“Oh God, no, Bessiewallis.”

She leaned back. “Just kidding. You always look so funny when you think you’re getting the pin.” Wallis stuck it back in her hat and stood to walk to the night table. Holding up her hands, she began to remove her gloves, revealing a large opal ring. “You don’t mind if I take my gloves off, do you?” Not waiting for a reply she added, “Have you had your morning coffee?”

”No.”

“Oh my. Let me pour it for you.” With her back to Sol, Wallis opened the top of her opal ring, emptied a white substance into the coffee cup and stirred. “Here, you must drink it all.” She lifted it to his lips.

With apprehension he emptied the cup and fell back on the bed.

“I told you of my adventures in China, didn’t I? I loved exploring all the shops in the Shanghai marketplace. It was so sinful. I found an old woman who sold all sorts of fascinating potions. I bought a powder ground from some herb with such a long name I can’t even begin to remember how to pronounce it. Do you know how long it takes for that poison, once ingested, to work its way through the body and kill you? A week! That gives me time to go to Europe. Before you die.”

Tears filled his eyes. “I’ll tell. You won’t get away with it.”

“I forgot to mention the first symptom is immediate paralysis of the vocal cords. You won’t be able to tell about anything.”

Sol opened his mouth to speak. No sound came out. The potion had already taken effect.

“Good-bye, Uncle Sollie,” Wallis said, walking to the door. “You be a good boy. And, by the way, burn in hell.”

A week later, Wallis and Bessie strolled along the Champs-Elysees when they stopped at a news stand to buy a paper. Actually, Wallis was the one who wanted something to read because Aunt Bessie was prattling on about the upcoming debutante season in Baltimore. Wallis had grown beyond her aunt’s interests. The world of espionage was much more fascinating.

She tapped her foot as the man in front of her took too long buying a magazine. Wallis imagined he was more concerned with flirting with the newsstand girl. He was a tall man in a vanilla ice cream colored suit. His black hair was slicked-back. When he finally paid, he turned, smiled and gave a smart bow. Wallis found it impossible to remain miffed because he had a pencil-thin moustache and an appallingly deep dimple in his chin.

After he moved on, one particular headline on the front page caught her attention.

“Baltimore Inventor Dies.”

Wallis pulled coins from her purse to pay for the newspaper and scanned the story to see if it speculated on cause of death. She smiled when she read the words “natural causes.” Then she handed it to Aunt Bessie who looked at the headline.

Without any emotion she commented, “I never much cared for Sol.”

“Oh, he was all right, as long as he was going to leave everything to me.”

“Does the story say anything about the will?” Bessie asked.

In a few moments they were seated at an open air café along the Seine. Before Wallis could continue reading Sol’s obituary she was distracted by the sight of the man in the vanilla ice cream colored suit sitting at a table across from them. He lifted his champagne glass as though in a toast. Doing her best to ignore him, Wallis slammed back her own glass of champagne before returning her attention to the story about Uncle Sol.

“Finally,” she announced. “Here it is. Mr. Warfield’s will left his entire fortune of five million dollars to build a home for destitute dowagers.”

“Destitute dowagers?” Bessie repeated. “I don’t think I know what that means.”

Wallis wadded the newspaper up and threw it in a nearby trash can. She motioned to the waiter to bring her another champagne. She was in the process of slamming it back when she heard a deep male voice.

“You mustn’t toss back champagne like it were a lager in a beer garden.”

“And who appointed you queen of etiquette?” Wallis looked up to see the man in the vanilla ice cream colored suit standing over her. She blew smoke in his direction.

“I’m in the champagne business. I sell wholesale to all the best restaurants in Europe.”

“In that case, sit down and point out the best champagne on the menu.”

“Only if you promise not to guzzle but sip.”

Wallis appraised him and smiled. “You’ve got a deal.” She refused to acknowledge Aunt Bessie’s profound sigh of resignation.

Burly Chapter Nine

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. Herman asked his parents to make burlap bears for his brother and sister for Christmas. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school, Tad was nicer and the tent show was coming to town.)

Herman and Tad ran out the front door and scrambled into the back of the pickup. Callie rode in the cab next to her father. They were well on their way down the road when Tad leaned over to Herman. “Can you keep a secret?”

Herman became scared because whenever Tad said something like that he was in trouble and going to get Herman in trouble too. “I guess.”

Tad smiled as he pulled from under his shirt Burly.

“Burly!”

“Shush,” Tad whispered. “I said keep it on the QT.”

“Thank you.”

Tad shrugged. “I thought it wouldn’t hurt anything, and, heck, you’ve been a pretty good kid, making good grades and, well, you pull your weight around the farm.”

“I love you, Tad.”

His brother stiffened. “Aww, don’t get sloppy on me.”

The rest of the ride went in silence, but it was the happiest silence Herman ever shared with Tad. When they arrived at the tent they had to take seats towards the back since it was almost filled. Herman had never seen so many people together in one place, which also made it very hot. The sides of the tent were rolled up so air could move through, and people with the show were giving out hand fans.

“Hi, Herman!” a boy called out.

Herman looked up and smiled. It was one of the nicer boys from school, Gerald Morgan.

“Who’s that?” papa asked.

“Oh, a boy from school.” Herman stopped smiling long enough to make sure Burly wasn’t showing from underneath his shirt and then gave Gerald one last wave.

They hadn’t been there long when a band marched out and sat right in front of the stage. Music began, and the curtain opened. Herman cautiously pulled Burly from under his shirt so he could watch too. Glancing over at his father, he saw a happy grin on his face. The actors came out and began talking. To be honest Herman didn’t really understand much of what they were talking about or who was who. One fellow was definitely a bad guy, who talked nasty to people and threatened all the pretty girls on stage. Another actor was the good guy. Everybody seemed to like him. Finally there was Toby. Harley Sadler didn’t look a thing like he did that afternoon. He had on a silly red wig and had freckles painted on his face, and he wore funny looking wooly chaps. When he came on stage everyone else sort of disappeared because the entire audience laughed at Toby.

Partway through the show papa leaned over to Herman, who jumped and quickly put Burly under his shirt. “Can you see all right, son?” he whispered.

“Kind of,” Herman replied.

Papa looked behind him to make sure there wasn’t anyone he would be blocking and then lifted Herman to his shoulders.

At first Herman had a few butterflies in his stomach because he was so high but he could see better. It felt good being so close to his father so the butterflies soon went away. After a while Herman asked his father if he was hurting his back.

“Not to mention, as long as you’re having a good time,” Papa replied.

The hero beat up the bad guy with the help of Toby. One of the pretty girls turned Toby down when he asked her to marry him, which didn’t seem right. But another pretty girl did marry the hero, which made the audience cheer. The curtain came down, the band played some happy-sounding music, and the audience applauded.

On the way out Herman smiled with the satisfaction of knowing exactly what a tent show was now and of feeling love flowing from his family. Then he saw something that broke the warm feeling. Off to the back left was a section roped off for black people. He hadn’t noticed it when they came in. Indeed, it was the first time Herman had ever noticed that black people were treated differently and it bothered him. As his father lifted him off his shoulders and onto the ground, Herman’s first reaction was to ask his father about it, but he decided not to say anything.

He had almost forgotten the separation of the black people when they got home. Herman was about to walk into the house when his father called him over to the shed where he was putting the pickup away for the night.

“How did Burly like the show?” Papa asked.

“What?”

Papa smiled knowingly. “You better take him out from under your shirt now. He’s going to rub your skin raw.”

Herman pulled Burly out. “How did you know? Did Tad tell?”

“Why? Did Tad know?”

“Um, no.” Herman didn’t want to get his brother into trouble.

Papa patted Herman’s back. “Don’t worry about it. Get on to bed.”

Herman was leaving when he decided to ask about the black people. His father’s serene expression changed as Herman spoke.

“Oh, the coloreds.” The last word floated up through Papa’s nostrils as though it were the stench of rotten eggs. He turned away from Herman, his way of saying a conversation was over. “Don’t worry about them.”

Now Herman wished he hadn’t brought the subject up. It put a sour ending to a wonderful evening. When he climbed the ladder to the loft he found Callie and Tad already asleep. He took his clothes off, opened his window and climbed into bed.

“How did you like the show?” he asked Burly.

“What I saw I liked. Of course, I couldn’t see much from under your shirt.”

“I’m sorry,” Herman whispered.

“Oh no. I was glad I got to go, no matter what.”

Herman smiled as he nestled into his pillow. “Wasn’t it nice of Tad to bring you?”

“Of course. I keep telling you he loves you.”

Herman sighed. “Yes. But often it comes as a surprise.”

From across the room came two other bear voices.

“How did you like the show?” Pearly Bear asked.

“Was it fun?” Burly Senior added.

“Oh yes, mama, papa,” Burley replied. “Even though I did have to sit under a shirt.”

“Sit under a shirt?” Burly Senior said with a hint of indignation. “Herman, why did you do that to Burly?”

“I—I was afraid of what Papa would say,” Herman stammered.

“But your father knew all along,” Pearly said. “You would have been better off being honest, and then Burly would have had a better view.”

Herman frowned and thought about the black people again. “Are people being dishonest about black people?

“I don’t know,” Pearly replied. “I just know about bears.”

And then Burly Senior asked, “But are bears and people much different?”

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Twenty

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Soon to join the world of espionage is Wallis Spencer, an up-and-coming Baltimore socialite.

In April of 1927 David found foolish emotion creeping up through his body and felt his heart and mind working together to undermine the British Empire. Freda Ward, his mistress since 1918, began to occupy more of his thoughts since he returned from the failed mission to Manhattan. On the liner across the Atlantic, David encountered several ladies willing to share his bed but a strange thing occurred. He preferred to spend his hours writing letters to Freda.

This was a problem he had never considered when MI6 first approached him when he was in school to train to serve in the elite espionage corps. His love-deprived childhood and tortured school days filled with bullying convinced him true, nourishing enduring love was a cruel myth. At first his relationship with Freda was no more than his usual vent of sexual frustration and a convenient cover for his espionage activities. But now he considered the possibility that true love actually existed.

On this particular day David drove his Ace roadster coupe to unoccupied country home near Windsor Castle with Freda in the passenger seat. He gunned the two-liter six-cylinder engine.

“Now do you like my new car?”

“Very sporty, like you,” she said.

“It’s exactly like the one Victor Bruce drove when he won the Monte Carlo Rally in 1926. I was simply dippy for it so I special ordered it.” He kept glancing over at her trying to read her inscrutable face. Usually she glowed at him with something likening a mother’s love. Today he saw a hint of disapproval and exasperation.

“I was on a round of princing recently out here in Surrey—I had to hand out rosettes to a bunch of cows or some such foolishness–when I came upon this property and became quite dippy about it.”

“I wish you wouldn’t use that word,” she interrupted.

“Which word?”

“Never mind. You’ve said it twice in consecutive sentences.” After a shake of her head, she smiled warmly. “Continue.”

They rounded a brushy corner and the manor house with its fanciful towers and curving walls appeared.

“There it is, Fort Belvedere. It screams gothic revival architecture, doesn’t it? Anyway, I did a bit of digging and found out it was built in 1750 as a folly. You know what a folly is, don’t you?”

“Yes, I do, but playing professor gives you so much pleasure.” Freda emitted one of her motherly sighs. “Do explain it to me.”

David parked in front of the house and jumped out to open Freda’s door. “This one was built to look like a military fort, but the only guns ever used around here were for hunting weekends. A small hunting lodge, just for fun, pretty to look at but not much use for anything else. My God, sounds like me, doesn’t it?”

“Well,” she paused long enough to give him a nudge, “you’re not all that pretty.”

He guided her to the front door and unlocked it. “It was expanded in 1828 to meet the requirements as a full-scale hunting lodge and used on and off ever since. Now the kick of it is that it’s one of my father’s properties and I’m trying to figure out a way for someone on his staff to insert the idea into his sotted brain to give it to me. My God, I am a grown man and I should have my own house, don’t you think.”

“Yes, I think it would do you some good to be responsible for something for once in your life.” Freda looked around at the dark wood flooring and paneling. “But it will need a bit of redecorating, I think.” Her eyes flashed with an idea. “Why don’t you make it a home for deprived orphans of coal miners?” She walked out of French doors onto a terrace overlooking a large wooded area. “Think of all the fun they could have playing among the trees and planting gardens and such.”

“Oh, there you go, playing angel waif again.” He gazed at her with a mischievous grin. “Now how am I to host weekend parties with plenty of naughty friends when all those children are around?”

“Well, that’s what I meant.” She gathered her thoughts. “Don’t you think it’s time to stop being naughty, at least on such a grand scale?”

He took her hand and guided her to the shade of the trees. “The same idea had crossed my mind. How do you see this as a honeymoon cottage?”

Freda’s mouth opened but nothing came out for a moment. “Remember, I am married.”

“But not happily. Otherwise, why would you be mucking around with me?” Before she could form a reply, David continued. “Of course, you couldn’t officially be queen, when it comes to that, but there is such a thing as a morganatic marriage—that’s where we could be legally married and our children would be royal but not you. That wouldn’t be so bad would it? I mean, I think the tweedy types would go for it. They like you. After all, your father is a member of Parliament and vice-chamberlain of the royal household. And you’re so discreet.”

He held his breath. He did not know if he really meant it or not. If he married—actually married and conducted a normal family life—his life as an espionage agent would be over. Being an agent gave his life meaning. But a life with Freda could also give it meaning.

Gently folding her fingers in front of her mouth, Freda said, “Do you remember earlier when I ask you not to use a certain word but I declined to say which word it was?”

“Yes, but before you say anything else, please consider this. We have been lovers since 1918. Ten years. Good grief, I know some people who can’t stay married for ten years. Do you remember when we met? It was at a dance hosted by some woman. I can’t remember her name. She had her brother there. I think she was trying to shop him around.”

She sighed and shook her head. “It was Maud Kerr-Smiley, and she wasn’t shopping her brother around. He was quite debonair and wealthy. In the shipping business, I think. Simpson, that’s his name. Ernest Simpson. Oh, here we go again. You can’t keep your mind focused and you drag me along into your wonder land.”

“No, no. All this has a meaning. In the middle of the dance we had to dash off to a bomb shelter where we became close, very close. I knew then. You were exceptional.”

“And you look at me with your puppy dog eyes and say sappy things like that.” She exhaled in exasperation. “Please let me finish.”

“Very well.”

“You said you were dippy for this your car and then said you were dippy for this property.”

“So?”

“Dippy is such a childish word.”

“”It’s a joke. It’s fun to use words like dippy.”

“David, I would divorce my husband because he is many years older than I and is rather, well, stodgy. But I am not ready to turn in an old codger for a little boy. When I do—or if—I remarry, I want to marry a man my own age, mentally, emotionally, spiritually, someone who would not use words like dippy.” She paused to wrinkle her brow. “Have I hurt you terribly?”

He smiled and turned away. “Oh, if you ever knew.”

“What?”

David rested his butt on a moist stone wall and cocked his head. “You know how I seem to make fun of my duties, you know, calling it princing?”

“Yes,” she replied softly.

“Well, it’s all a series of stunts, camouflage and propaganda. Think about it. Why do they really need to be trotting me around the globe shaking hands?”

“Because you are so good at it?”

David chuckled. “I’ve been told that before.”

“What?”

“Never mind.” He went to Freda to kiss her lightly on the lips. “No, I am not hurt and I understand.” He looked around at the house, the terrace and the woods extending into the horizon. When Daddy gives me this place, will you play hostess? Redecorate it for me?”

“Of course I will,” she replied, sounding more like a mother than a lover.

“I’m looking forward to doing the gardening myself. I really do like getting my hands dirty, you know.” He waved towards the trees. “A hundred acres of trees. Think of the things I could plant there, and nobody would ever know.”

“You scare me sometimes, David. I never know when you’re making a joke and when you’re serious.”

He pulled a small stuffed teddy bear from his jacket pocket and tenderly placed it in her palm and closed her fingers around it.

“This is for you. Always keep it with you. From time to time, pull it out and look at it to remind yourself of the one brief moment when the Prince of Wales was completely sincere.”

Lincoln in the Basement Chapter Forty-Four

Previously in the novel: War Secretary Edwin Stanton holds President and Mrs. Lincoln captive under guard in basement of the White House. Janitor Gabby Zook by accident must stay in the basement too. Guard Adam Christy reports on his condition each evening to his sister Cordie and fellow hospital volunteer Jessie Home. Tad Lincoln becomes ill.

Mrs. Lincoln would know what to do, Adam Christy told himself, but she is not the woman tending to Tad right now.

“I suppose so,” he muttered.

“I don’t know,” Neal said. “If it’s his appendix, it could bust right soon, and he’d be dead before morning if nobody does anything about it.”

“Neal.” Phebe slapped his arm.

They walked off fussing at each other as Adam nervously unlocked the door. Could Tad die? He was worried, as he entered with the three pots.

Gabby took his. “That Mr. Stanton, do you talk with him often?” He kept his eyes down.

“Yes.”

“Please tell him—in a nice way, because I don’t want to get him mad, since he’s so hot-tempered in the first place—to be nice to Cordie.”

“I will.”

“She doesn’t feel well.”

“Oh.”

“I think she has the family disease.”

“What’s that?”

“Sitters disease.”

Gabby turned to scurry behind the boxes and crates. Mrs. Lincoln came from behind her curtain combing her hair out, and for the first time since Adam had known her, wore a look of quiet resignation instead of pent-up anger. She smiled at him.

“Back already? My, you’re quick like a bunny rabbit.”

“Yes, ma’am.” Adam felt his face flush as he thought of Tad and his bilious condition. As had become the custom, he placed the chamber pots down outside the curtain and turned to go.

“Private Christy, is there anything wrong? You’ve the oddest expression on your face.”

“No, ma’am.” He turned back and felt his face turn redder. “There’s nothing wrong.”

“Nonsense.” She clutched the comb in both hands. “Your face is as red as a beet.”

“Well, I—I well…”

“Spit it out, boy,” Mrs. Lincoln ordered.

Lincoln, his collar undone, exposing masses of black hair on a bony chest, stepped from his private corner and put an arm around his wife’s waist and squeezed.

“It’s—it’s personal, and private.”

“You’re lying,” she declared.

“No, I’m not!”

“Now, Molly, no need to harass the boy so late at night. He needs his rest, and you need yours. I definitely need mine.”

“It’s Tad,” she whispered. “Something’s wrong with Tad.”

Adam’s eyes went to the floor.

“It is.” Her voice began to mount to its usual stridency. “I can tell. Oh, my God! Something’s wrong with my baby.”

“Come on, Private, we don’t believe in killing the messenger of sad tidings,” Lincoln said. “What is it?”

“The kitchen help said your son wasn’t feeling well,” he said. “They said he was bilious.”

“Well, that’s not so bad,” Lincoln replied.

“Not so bad!” Mrs. Lincoln struggled to free herself from his grip. “What imbecility is that? Haven’t you heard of appendicitis? Food poisoning? It could be any number of terrible, terrible things, and you say not so bad?”

Lincoln turned to Adam. “Why don’t you go upstairs and do a little reconnaissance work for us?”

“Yes, sir.” Adam left and went up the service stairs, his heart pounding so hard he could barely hear the straw mats crunching under his boots. On the second floor, he went straight to Tad’s room, where he found Alethia wiping the boy’s head with a wet cloth. To the side was a bucket filled with vomit.

“Poor child,” Alethia said as she looked up at Adam, “he must have eaten green fruit again.”

“No, I didn’t,” Tad protested.

“Is he going to be all right?”

“Oh, I think so.” Alethia smiled and stroked his cheek. “I gave him a dose of subnitrate of bismuth.”

“It tasted awful,” Tad said.

“But you haven’t thrown up since,” Alethia said.

Adam breathed deeply “That’s good.”

“I want Mama.” Tad looked from Alethia to Adam and back again. “My real mama.”

“Why, I don’t know what you’re talking about,” Alethia replied.

“I think you’re a very nice lady who looks like Mama, but you’re not her. And that man isn’t Papa,” Tad whispered conspiratorially. “It’s part of a war plan. I got that part figured out.” His bottom lip crinkled. “But I don’t feel good, and I want Mama.”

Adam stared at Alethia, not knowing what to do, and hoping she had some answer, but the scared look on her face revealed she knew as little as he did. He jumped a little as he suddenly became aware of Duff’s presence in the room.

“What do you think?” he asked him, frowning.

“I think you should tell his parents that he’s received medicine and is feeling some better, but wants to see them. They deserve to know that much.” Duff looked at Tad and smiled. “I knew you were a smart boy. Thanks for keeping our secret.”

“You’re welcome,” he said. “But I still want Mama.”

“Of course, it’s not my decision,” Duff said to Adam, “but I think it’d behoove us to keep this child happy and willing to go along with our game. Isn’t that right, Tad?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I don’t know.” Adam shook his head. “I don’t know what Mr. Stanton would say.”

“What difference does it make what that old poop thinks?” Tad chimed. “My papa is in charge of this switch, ain’t he?”

“Of course, he is,” Duff said.

Adam and Alethia exchanged nervous glances.

“This young fellow here just likes to keep everybody involved in this caper happy,” Duff continued, smiling at the boy and reaching to muss his hair.

“Hmph, I don’t care if old Mr. Stanton is happy or not,” Tad said in a pout.

“I’ll see what Mr. Lincoln wants.” Adam’s stomach tightened as he lied to Tad. More and more, he feared the threads of Stanton’s tapestry were unraveling—the war continued, the boy knew and could talk, and the kitchen help was curious, too curious.

“Yes.” Alethia patted Tad’s cheek. “Soon you’ll get a hug from your mama. But you must promise not to tell anyone.”

“Not even Robert?” he asked.

“Especially not your brother,” Duff replied.

“Good.” Tad smiled impishly. “I like keeping secrets from my brother.”

In a few minutes, Adam was in the basement again, unlocking the door to the billiards room. Inside, Mrs. Lincoln rushed to him, grabbing his arm.

“How’s Taddie? Is he all right?”

“He’s fine. The lady thinks he has just a plain old bellyache. She gave him subnitrate of bismuth.”

“How much?” Mrs. Lincoln’s eyes widened. “Subnitrate is powerful medicine. If a child is overmedicated…”

“Now, Molly, I’m sure the lady upstairs knew the right amount to give him,” Lincoln interrupted as he walked up.

Adam noticed the look in Lincoln’s eyes did not match the moderation in his voice. Not even on the day he had brought the president to the basement did he see such anguish as he observed now. It made him nervous.

“Something else is wrong,” Mrs. Lincoln said. “I can tell. Your emotions are written on your face like Mr. Dickens writes stories on a page. What is it?”

“Tad is all right,” Adam repeated.

“What is it, son?” Lincoln asked ominously.

“It’s nothing, really.”

“Tell me!” she demanded, trying to control her hysteria, as Lincoln’s big hands clutched her shoulders tightly.

“He wants to see his mother.” Adam’s eyes wandered around the room and spotted Gabby peeking from his corner. He must have courage, or else he would dissolve into another Gabby Zook.

“So he knows that woman is a fake.” Mrs. Lincoln smiled with vindication.

“Of course he does,” Lincoln said, relaxing a bit. “He’s smart, just like his mama.”

“Then bring him down here. It won’t hurt. He already knows,” Mrs. Lincoln insisted.

“He’s kept the secret for two months now,” Lincoln added. “He can be trusted.”

“Oh, I know he can be trusted,” Adam agreed. “It’s just…”

“It’s just what?” Lincoln’s tone became ominous again.

“I don’t know if Mr. Stanton will approve.”

“Stanton! That evil man!” Mrs. Lincoln’s hands began to flail about.

“Now, Molly,” Lincoln said, forcing her hands down, “let me handle this.” He solemnly looked at Adam. “Go get Mr. Stanton’s approval right now.”

“He doesn’t like to be disturbed,” he explained.

“This woman’s already lost two babies.” Lincoln suddenly grabbed the front of Adam’s rumpled blue tunic, pulling him off his feet to eye level. “She gets fearful upset when another is ailing and she can’t pet him,” Lincoln stated softly, coldly. “So I suggest you get Mr. Stanton’s permission to bring that boy down here.”

Adam gasped in surprise as he nodded obediently. He quickly, painfully, became aware of Lincoln’s strength and anger. Scrambling for the door and fumbling for the keys, he followed the orders of the president of the United States.

Burly Chapter Eight

(Previously in the book: For his fifth birthday Herman received a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. Herman asked his parents to make burlap bears for his brother and sister for Christmas. As Herman grew up, life was happy–he liked school, Tad was nicer and the tent show was coming to town.)

That night as Herman lay in bed he held Burly close. “Isn’t it exciting, Burly?” He didn’t hold his bear too close because it was hot in the loft. Three small windows were open by each of the beds. Herman slept in his undershorts, but there wasn’t enough breeze to keep him from sweating.

“Yes, it is exciting,” Burly said. “Nice things like that help keep your mind off how uncomfortable the heat is.”

“Tad said this man Harley is real funny. I don’t know what he does exactly, but I can’t wait for us to see it.”

“I’m glad you want Callie and Tad to have a good time too.”

Herman tickled Burly’s tummy. “No, I mean you. I can’t wait for you to see Harley.”

“No, Herman, I can’t go. They won’t want stuffed bears coming to their show.”

Frowning, Herman asked, “Why not?”

“I don’t know for sure. I just know if you asked your father he’d say no.”

Herman slumped down on his pillow. “I don’t know if I want to go if I can’t take you. It won’t be any fun without you.”

“Of course it will.” Burly paused to think. “Imagine how much fun you’ll have telling me all about it later.”

A smile crept across Herman’s face as his eyes fell heavily and a breeze finally blew across the bed.

Wednesday, the day of the tent show came to town, took on the same magical anticipation as Christmas. Each school day wound down slowly, and each chore at home took forever. Instead of twenty spelling words on the final test of the year, Herman could have sworn the teacher called out a thousand. And on the last day of school Herman was sure the teacher moved as though she were plowing through mud up to her waist. He didn’t even care about the grades on his report card, although they were very good.

“Hmph,” Tad said with disdain as he looked at Herman’s card, “grades don’t mean a thing.”

Herman would have been upset if he hadn’t seen Callie smile and wink at him.

Tuesday night was the longest night in Herman’s life, for there was nothing so exciting as the complete unknown. And that’s what the tent show was to him. What did Harley Sadler look like? Was he like a movie star? Big and good looking? Did he have a funny voice? What exactly did make Harley Sadler funny? Herman couldn’t wait to find out.

Tad, Callie and Herman got up early, ate quickly and ran out the door to go to town before the tent went up. As he flew out the door Herman heard his mother cough loudly and deeply. He paused to go back when Tad yelled at him to hurry up.

The hurly burly on the empty field next to the high school was enough to scare Herman, but Callie held his hand so everything was all right. Finally the tent was up and a short, fair man with sandy blond hair sauntered up to the large group of boys and girls eagerly awaiting the word. He had a funny, lopsided kind of grin and a mischievous twinkle in his eyes.

“I don’t suppose I could find anybody here willing to put up a few chairs for me for a ticket to the show tonight?”

‘You bet, Toby!” Tad yelled out with all the other children.

So this was Harley Sadler. He certainly didn’t sound funny. He had a pretty deep voice. And he didn’t really look all that funny. Mostly he looked like a rich businessman. On the other hand, his smile, and the look in his eyes, they were funny, Herman decided. More than that, they were exciting because they hinted at funnier things to come.

“Well, Herman, come on.” Tad tugged at his sleeve. “Let’s go!”

Herman was embarrassed he had been caught gawking at the famous actor, but Harley didn’t seem to mind. He just laughed and patted Herman on the head. There were so many children scrambling for chairs that Herman only got to set up three chairs before they were finished. At first he was afraid he hadn’t done enough work to earn the ticket, but he forgot that quickly as he was the first child Harley gave a ticket to.

“Now hang on to that,” Harley said, winking at Herman.

When all the tickets were distributed Harley said loudly, “Be sure to tell your folks that tonight is ladies night. All women get in free when brought by a man buying a ticket!”

“Oh boy!” Tad exclaimed as they hurried home. “Do you know what that means? It means papa will have to buy only one ticket! Mama’ll get in free!”

“This is going to be so much fun!” Callie giggled as she skipped beside Herman.

Life couldn’t be happier, Herman decided as he looked at his sister’s face and then his brother’s.

“And Burly will get in free too!” Herman chirped, forgetting what his little bear had warned him about the bear’s prediction he wouldn’t be allowed to go.

“Aww, Herman, you’re not going to drag along that toy bear, are you?” Tad moaned.

“If papa says it’s all right, why should you care?” Callie shot back, putting her arm around Herman.

When they came through the front door, they saw their father entering from his bedroom.

“Guess what!” Herman said loudly, “Mama can get in free!”

“Shush,” Papa hushed him with a finger to his lips as he motioned the children to the table to sit down. “Your mama’s not feeling good. She fainted this afternoon.”

“Oh no!” Callie gasped.

“Did you get the doctor?” Herman asked.

“Don’t be dumb,” Tad chided him. “We can’t afford the doctor.”

“That’s right, son,” his father said. “But—but I don’t think she’s too bad. I don’t think though we should go to the show tonight.”

All three children knew better than to protest, but Herman couldn’t help but let out a little groan.

“I know it’s a big letdown—“

“Woody!” mama called out weakly from the bedroom.

Papa stood and went into the bedroom. A few minutes later he came out. Herman tried to figure out what he was going to say from the look on papa’s face, but Herman couldn’t guess what the faraway look on his eyes meant.

“Hmm, your mama says she’s not that bad, that she wants us to go on to the show. She’ll be fine by herself.”

“I could let Burly stay with her,” Herman offered weakly.

Papa looked at him in a blur. “Who? Oh no, that’s all right.” He looked around the room as though he were helpless. “Hmm, Callie help me with supper. Tad, tend the animals in the barn.”

Tad left while Callie and papa turned to the kitchen. Herman quietly went to the loft and got Burly to take to his mother. He slowly opened the door so it wouldn’t creak and stepped in. He approached the bed where mama was sleeping restlessly. The dark spots under her eyes and the paleness of her skin became very real to him for the first time and it scared him.

“Mama?” he whispered.

Her eyes opened and she smiled. “Hi, baby.”

“Would you like Burly to keep you company tonight?”

She laughed and touched his cheek. “No, thank you, honey. It’s so sweet of you to offer.”

The door swung open and Herman heard his father’s voice.

“Herman, I thought I told you not to bother your mother.”

“That’s all right, Woody,” she said softly. “I wanted to see my baby.”

“Get out,” papa ordered. He paused to chuckle a bit. “Don’t you have chores to do?”

“Yes sir,” Herman replied meekly.

He hurriedly returned Burly to the loft and went outside. Supper went by very quietly, almost sadly, considering where they were going that evening. Papa took a tray of food into the bedroom and shut the door, staying with mama the entire meal. After he came out, Callie cast a quick glance at Herman and ventured a question.

“Could Herman take his bear to the show?

Papa turned to look at Callie and then at Herman. “Now why would you want to do that?”

“I don’t,” Herman protested.

“This afternoon he said he wanted to,” Callie replied.

Herman noticed Tad remained quiet during the exchange. He expected his brother to say something mean, but Tad almost never did what Herman expected.

Finally papa announced, “It’s time to go.” He actually was smiling. “Each of you may go in to see your mother, but don’t stay too long.”

“I want to go first!” Tad replied, heading for the bedroom.

“Don’t run and be quiet!” papa reminded him, causing Tad to slow down.

Callie went for a kiss. Then it was Herman’s turn. Mama gathered her baby into her arms and kissed him.

“Have a good time and obey your papa,” she whispered, her breath smelling of some foul medicine.

As Herman came out of his parents’ bedroom he noticed Tad had just come down the ladder from the loft.

“Come on, boys, or we’re going without you!” papa called from outside.

David, Wallis and the Mercenary Chapter Nineteen

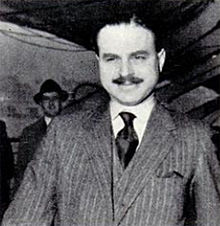

Ernest Simpson

Previously in the novel: Leon, a novice mercenary, is foiled in kidnapping the Archbishop of Canterbury by a mysterious man in black. The man in black turns out to be David, better known as Edward the Prince of Wales. Soon to join the world of espionage is Wallis Spencer, an up-and-coming Baltimore socialite. David and Wallis are foiled in their attempt to protect a socialite’s jewels.

By Christmas 1926 Wallis was visiting her college chum Mary and her husband Jacque Raffray at their elegant apartment on Washington Square in New York City. Aunt Bessie was with her, like a proper chaperone, but she never got in the way of Wallis having a good time. When the two young women shopped and lunched, Bessie stayed in the apartment reading the latest fashion magazines. Wallis and Mary lingered in discreet cafes, sharing intimate details of mutual friends.

On Christmas Eve the Raffrays held a party for their dearest and closest acquaintances. Everyone admired the decorations, table settings and music, but the party didn’t really begin until the bootlegger arrived. Bessie retired to her room early, as was her custom on trips with Wallis. After all, she didn’t want to be in the way. Amidst the giggles and chatter, Mary caught Wallis by the crook of her arm and guided her to a couple on the far side of the tree. They looked more than a little bored.

“Wallis, I want you to meet a fascinating man,” Mary whispered. “He’s in the shipping business and holds dual American and English citizenship.”

Wallis had not quite focused on the introduction until she remembered the part about dual citizenship.

“Hello, I’d like you to meet my friend Mrs. Wallis spencer.” Mary nodded to the couple. “Wallis, this is Ernest and Dorothy Simpson.”

Wallis looked at him closely. He was more than passably handsome, and his wife looked like she was in a perpetual state of grump.

She scooted closer to her man.

Wallis smiled and extended her hand, pretending not to notice the wife smiled back and extended her hand. Wallis grabbed Ernest’s hand instead. A low grumble escaped Dorothy’s lips.

“I just love a man with dark hair and mustache,” Wallis mumbled.

Ernest’s eyes twinkled. “Aren’t your husband’s hair and moustache dark?”

“Well, “she paused so a naughty smile could flicker across her thin, heavily painted lips, “some moustaches are better than others.”

“Ernest,” Dorothy interrupted with in a brusque tenor that could not be ignored. She paused to smile. Her own shade of lipstick was a soft, lady-like coral. “As I was telling you, I am coming down with one of my dreadful headaches. Really, we must leave now. I want to feel my best at Christmas dinner tomorrow with Mommy.” After a second, she added, with a condescending air, “Dear.”

Wallis raised an eyebrow. “Oh. You aren’t attending the midnight candlelight service at your church?”

“Why, no.” Dorothy seemed to be caught off balance. “Are you?”

“No.” Wallis caught Ernest’s elbow to lead him away. “Ernest, darling, you must see the view from the terrace. It’s really quite remarkable. You can see all the way to Times Square.”

They stood outside and looked in vain for the lights of Broadway. The breeze caused Wallis to shudder.

“Hmm, I was sure you could see Times Square from here.” She leaned into him. “Oh dear, it is a bit chilly, isn’t it?” Looking up into his eyes, she asked, “Now how exactly do you come to hold dual citizenship? It sounds exquisite.”

Before he could respond, Dorothy stormed through the door, already wearing her fur and extending Ernest’s overcoat.

“I must insist we leave immediately.” She shoved the coat into his hands and pushed him away from Wallis’s side. “It was simply wonderful meeting you, Mrs. Simpson—Spencer. I hope you have a safe trip home.”

Early in the morning, the day after Christmas, the telephone rang. Mary answered, listened then extended the receiver to Wallis who took it and purred a hello. Bessie sat in a nearby easy chair, reading the New York Times women’s section, particularly the wedding announcements.

“Hello, Wallis. This is Ernest. I hope you had a truly merry Christmas day.”

“Thank you, Ernest. How kind of you to call.”

“Have you ever visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art?”

“Why, no. I don’t think I’ve ever been to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.”

“Don’t you remember, dear,” Bessie said. “We were there last week.”

Wallis snatched the newspaper from Bessie’s hands and threw it on the floor while still talking on the phone. “I hate to admit it, but I’m much more of a country girl. Love tromping through the woods. I’m terrible, aren’t I?”

“Of course, not. I’m an outdoorsman myself.”

“Yes, you are terrible, Wallis.” Bessie bent over to pick up the papers. “Why on earth did you toss my paper on the floor?”

“Do I hear your aunt?” Ernest asked.

“Yes, the poor dear is having another one of her fits. It’s best that we ignore her.” Wallis wagged a skinny finger at Bessie. “I hope you are volunteering to take me to the museum.”

“Are you available this afternoon?” he asked.

“Of course, I am.”

“Think your aunt would like to join us?”

“She’s having one of her fits, remember? It’s best to leave her alone in her bedroom.”

“Well, I like that,” Bessie muttered good-naturedly.

“I really do want to be a cultured lady. What I don’t know about art I’m sure you could teach me. After all there’s more to life than…well, life.”

“Well spoken. I’ll pick you at noon for lunch and then we’ll take on the museum.”

After she hung up, Wallis giggled.

“You do know it’s just as easy to woo a single man as a married one.” Bessie settled back in her chair to resume her reading.”

“But I don’t want it to be easy. What’s the thrill in that?” Besides, Wallis thought, it was her duty to king and empire to seduce Mr. Simpson.

That afternoon Wallis took Ernest’s arm as they began to explore the galleries.

“It’s a shame Dorothy couldn’t join us.” She was surprised by how sincere she sounded.

“Yes, she has a terrible headache. Too much Christmas cheer, I think.”

He took time and particular relish to explain the impressionism found in a small Monet. After he finished Wallis pointed to the next painting. Her arm grazed across his chest.

“And what is that?” she asked with total innocence.

“That’s my chest,” he replied in amusement.

“What?”

“You have your hand on my chest.”

“So I do.” She patted it. “How nice. Eventually she removed it and pointed again at the other painting. “I mean what is that painting over there?”

He smiled and placed his arm around her shoulders. “Well, let’s go find out.”

It had not been a full week into the new year when Wallis rang up Ernest with the excited announcement that Rose-Marie was coming to Broadway again.

“I am beside myself. I love the music though I’ve never seen it on stage. Please tell me you will be available the night of the 27th. That’s the opening night. It would be so much fun if we could see it together. Oh, of course, Dorothy if the poor thing is feeling well. Does she still have that dreadful headache?”