Half a century ago when I was a little boy in a rural Texas town, I heard that people who danced were going to hell.

Decent people didn’t dance, smoke, drink or vote Republican.

And if they did, they had the good manners not to let anyone know.

Once I mentioned to a church lady on a Sunday morning that I had bought a cupcake from the high school student council. I didn’t really want it but the two girls selling the tray of cupcakes were really cute and kinda flirted with me so I gave up a couple of quarters and enjoyed the cupcake.

“That was supporting dancing!” the woman declared. “Which is the same as supporting the devil!”

When I asked why she said the only thing high school student councils do was organize dances so when I bought that cupcake for fifty cents I was supporting dancing.

Well, that took the sweet memory off that cupcake.

Once I had the audacity to ask the preacher why dancing was sinful since it wasn’t one of the Ten Commandments nor one of the abominations listed in Chronicles Chapter 12. The next Sunday night he preached an entire sermon about how the Bible didn’t specifically say dancing was a sin, it did record that every time some one danced, something bad happened to people.

When the Israelites got bored waiting for Moses to come down from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments they danced around and they got smote down and good. When David danced naked in front of the Ark of the Covenant as it came into Jerusalem, he was denied the privilege of building the Temple. When Salome danced in front of King Herod, John the Baptist lost his head.

Well, I think all the fornicating before, during and after the dancing was what got the Israelites in trouble with God and not specifically the dancing. Also, David put Bathsheba’s husband on the front lines of battle to kill him off so he could marry her. That probably kept David from building the Temple more than the dancing. Finally, King Herod was just plain crazy. He didn’t need a dancing girl to give him an excuse to kill anyone.

Anyway, I kept all those thoughts to myself while I was growing up. Besides, I had this terrible suspicion that if I did try to dance I wouldn’t be very good at it. I had two left feet.

Fortunately, I married Janet who two right feet. We just had fun on the dance floor and didn’t care if anyone noticed. The nice thing about people who like to dance is that they’re having too much fun to judge anyone else’s abilities. I kept telling Janet that we needed to get a video from the public library about easy ball room dancing steps but we never got around to it.

As old people we occasionally went to events that feature orchestras that played the Big Band sound. All around us were people who had rhythm in their feet and smiles on their faces as they danced to jazz, doo wop, Latin and especially Frank Sinatra. For three hours the world went away and everyone went happy. I don’t go dancing anymore because Janet died of cancer and I lost my two right feet. I don’t know if that is a sin but it is a crying shame.

As for that church lady, I have a sneaking suspicion that she didn’t know what she was talking about.

Tag Archives: family

Dinner

“Now I want all of you to eat every bite of this,” Mother said as she sat down at the table. “I had another one of my headaches today while I was cooking.”

“Well, I helped cook,” Betty replied, sticking out her lower lip in a pout, as she spooned the turnip greens on her plate. “But I do love turnip greens, with lots and lots of bacon grease.”

“I don’t want any greens” Royce said. “Bacon grease upsets my stomach.”

“Bacon grease is yummy.”

“That’s why you’re a fat pig. You eat too much bacon grease.”

“Royce, if Betty wants to enjoy her food, that’s her right,” Mother said, putting a small dollop of potatoes on her plate. “These potatoes are delicious, but I don’t want to gain any more weight.”

Dad grunted as he piled the food on his plate and kept his head down.

Donny, the youngest, took the last cutlet, emptied the bowl of potatoes and covered them both with gravy.

“You little pig,” Royce said. “You took all the food. What if Dad wanted more? At least he works. I might have wanted more. I have a paper route. You don’t work. You don’t deserve to eat.”

“I help mother around the house,” Betty said, stuffing potatoes into her mouth. “If that’s not work, then I don’t know what is.”

Donny pushed the plate away and looked down.

“Why aren’t you eating?” Mother asked. “After all I went through to put it on the table.”

“Royce said I didn’t deserve to eat.”

“You’ve got to learn to not pay attention to what Royce says. Eat up or you’ll give me another headache.”

“I don’t wanna.”

“One of these days I’m gonna bop you over the head,” Betty mumbled, glaring at Royce. “Always picking on the baby.”

“I’m not a baby.”

“Then stop acting like one,” Royce spat.

“Father, what are we going to do? Donny won’t eat because Royce said something.”

“Eat your damn supper.” Father let out a belch before cutting another slice of cutlet.

“Why do you always have to upset the baby at supper?” Betty was on the verge of hysteria. “I think you’re just not happy unless you stir up a little hell.”

“Betty, mind your own business.” Mother ate the last forkful of potatoes on her plate. “Those potatoes were so delicious. I’m glad they’re all gone so I wouldn’t be tempted to eat anymore.”

“You’d have enough potatoes, Mother,” Royce said, “if the pig hadn’t put them all on his plate.”

“Oh no, if Donny thinks he can eat all those potatoes I want him to have them.” Mother sighed. “Go ahead and eat your potatoes, Donny.”

“Yeah, you little pig,” Royce added with a growl.

“Don’t call the baby a pig!” Betty’s face turned red.

“It’s just not fair!” Royce had tears in his eyes. “He gets away with everything ‘cause he’s the baby!”

“Father, what are we going to do with these children?” Mother shook her head. “It seems we can’t have a moment’s peace without somebody getting upset.”

“Everybody shut the hell up. And you eat your damn potatoes.”

“Yes, Father.” Donny slowly raised a forkful of food to his mouth.

“I’m just going to stop trying to fix a good meal anymore. Nobody ever wants to eat.”

Burly Chapter Five

(Previously in the book: Herman anticipated fifth birthday on the plains of Texas during the Depression. He was overjoyed to receive a home-made bear, which magically came to life when Herman’s tear fell on him. Before Christmas, Burly told Herman he wanted a family too.)

Herman and Burly went out to the barn after putting on their coats, for the East Texas wind made the winter cold even colder than it was. Herman’s coat was made of denim, and Burly’s was actually a piece of old flannel with a hole in the middle. Papa called it a poncho. Moving bales of hay, papa had his denim coat off and his sleeves rolled halfway up his arms. Ever since he hugged his father for giving him Burly, Herman wasn’t afraid of those worms.

“Papa? May I talk to you a minute?” Herman spoke right up.

His father looked around, his face all twisted up from working so hard, but when he saw Herman he smiled very big. “Yes, son. What do you want?”

“I was thinking, it would be nice if Callie and Tad could have burlap bears like Burly for Christmas. Mother said she would make them if you had the burlap bags to spare.”

“That’s a good idea, son. I have a whole stack of empty ones over in the corner. You pick out two for your mother to make the bears.” He patted his son. “I was worried I wouldn’t have anything to give them this Christmas. Yep, you had a really good idea.”

Herman smiled broadly because both his mother and father had told him he was good for thinking of the bears for his sister and brother. He was beginning to understand what they meant when they said in church that it was more blessed to give than receive. All of a sudden, though, his happy thoughts turned to worry. In order for the new bears to be real parents to Burly Bear, they would have to be able to talk, just like Burly. And that would mean they would have to come from the same magical kind of burlap that Burly came from. What did Burly say about how he made his burlap bag move under father’s hand to make him think of making the stuffed bear? Oh, Herman wished father wasn’t standing so close so he could talk to Burly and get his advice.

Herman slowly touched all the empty burlap bags, but they all felt the same to him. He went through the stack again.

“Haven’t you picked out two bags yet?” his father yelled at him.

“No,” Herman replied. Maybe it was his father who had the magic touch to pick out the exactly right burlap to make the magical bears. “Would you pick the bags for me?”

His father walked over laughing. “You’re a good boy, Herman, but sometimes you do act silly.”

Herman was afraid his father wouldn’t take time to pick the right ones because at first he just grabbed the two on top.

“These will do,” he said, but then he stopped and looked at the bags. “Oh no. That won’t do at all. They got big holes in them. Let me look again.”

Herman smiled to himself. Father would make the right selection this time.

“Here, take these.” He tossed two bags at Herman.

It wasn’t long until Christmas came to the little farm house near Cumby. Father found a cedar tree, cut it down and dragged it into the house, filling the air with sweet evergreen aromas. Mother popped corn, and Callie and Tad strung the kernels together and hung them on the tree. Father bought a sack of cranberries which were strung on the tree too. All three children cut and colored paper ornament until the tree became pretty enough for the holidays.

Christmas Eve the family gathered around the tree after a meal of chili and cornbread. Father cleared his throat which was a sign for everyone to become still and silent.

“Times have been hard this year, and your mother and I can’t afford to give you anything except what we’ve always given you—our love. So I want each of you to come to your mother and me, and we’ll give you our present, a hug and kiss.”

Callie led the way and gave father and mother the biggest hug she had. Tad looked down and shuffled his feet like he was sad he wasn’t getting anything else, but he was able to give his parents a warm hug. Herman skipped over and got his hug and kiss, barely holding back a giggle, since he knew that wasn’t all some of them were getting.

After the children sat down again, father said, “Now two of you are getting something extra.”

“Yeah, and I can guess which two it’s going to be,” Tad grumbled.

“No, I bet you can’t guess,” his father said.

Mother pulled out the two bears wrapped in old newspaper. “These are for you and Callie.”

“Oh my goodness! Thank you! “ Callie yelled as she grabbed her package and tore it open.

“For me!” Tad squealed, his eyes dancing. He tore into his gift.

Each held up their burlap bears and hugged them, and then ran to their parents.

“They’re wonderful!” Callie exclaimed.

“Yes! Oh thank you!” Tad appeared younger and happier to Herman.

“You should tank your brother Herman,” their mother said. “He’s the one who suggested I make them for you.”

Callie hugged Herman and kissed him on the cheek. “Oh Herman, you’re so sweet!”

And so, Herman got his second Christmas present, the wonderful feeling of giving to someone else. Unfortunately, Tad broke the Christmas spell by throwing his bear to the floor.

“I don’t want the old thing!” he growled. “Herman just did it so he could get people to say he was wonderful. And—and he knew I wouldn’t want a silly old bear so he’d end up having two bears, the little pig!”

Callie turned red and stepped toward Tad. “Oh Tad!” She stopped abruptly, looked at her parents and sat down. For a nine-year-old girl, she was learning to mind her own business, Herman decided.

“Tad, that’s not a nice thing to say to your brother,” his mother said softly.

“Well, that’s what he is, a little pig!” Tad kicked the bear across the room.

“That’s enough of that, young man.” His father stood. “We’re going out behind the barn.”

Forever With Mama

Mama told me all the stories of the great blinding light and times of darkness and cold. She did not live through them herself, but she assured me it was not so long ago. Before the great glow, never-ending darkness and cold, there walked upon the earth terrible giants who kindly fed us and just as ruthlessly crushed us underfoot.

These stories were fading from my memory, and I was afraid. They gave me a reason for living and the determination to keep my legs moving in the eternal search for food. If I could only find Mama she would explain why food made life worth living. Or, rather, what worthwhile reason made eating so important.

The last time I remembered being with Mama we were in the midst of our kind. We clamored over each other trying to find food. At one point my legs gave way, and I felt a thousand little legs on my back. I sensed their fear and desperation. There were so many of us, and no one knew what to do but keep scampering around. If we kept moving maybe we would find a gooey mountain that once was one of the giants. The giants had become our food.

I knew that I was not smart. When I didn’t know what to do, I often did absolutely nothing and hoped absolutely nothing happened to me. This also gave me time to think about things Mama told me. We needed food to exist, but if we could not find food, we should look for water to drink. Drinking water would keep us alive until we found food.

If I found a pipe, she told me, crawl up it because pipes always carried water. I bumped into a long round thing which I thought was one of those pipes Mama talked about, and I climbed on it and began to scuttle upwards. One of my feet slipped into a crack so I decided to crawl inside. Mama said water was always inside the pipe.

It was dry. My legs weakened. I didn’t know how much longer I could walk. Within my body was a growing perception that I no longer cared to move. I tried to control the panic. Just ahead, I came upon a hole. Crawling through, I found myself in a great basin. My spirits lifted. This was one of the places where water existed.

In the distance I saw a great brown mound. It was one of us. As I came closer I knew who it was. I recognized the pattern of the shell. I smelled its essence. My antennae touched its antennae. It was Mama. I nudged her, hoping that she was just sleeping. But she was not sleeping. All that was left was her dry shell.

Momentarily I considered leaving to continue my search for food and water but changed my mind. My fatigue overwhelmed me. My legs could move no more. I was with Mama. And all was good.

Burly Chapter Three

(Previously in the book: Herman anticipated fifth birthday on the plains of Texas during the Depression. He was overjoyed to receive a home-made bear, but his brother Tad’s ouburst ruined the moment.)

Herman climbed into the loft, took his clothes off and got into bed with Burly. He looked out of the window at the dark sky and thought how lonely he still felt. Burly was wonderful, and he could him hug him; but, Herman still felt lonely and sad. Part of it was because Tad made such a fuss and another was—well, Herman still didn’t know why. Again, as so many nights, tears began to fall from Herman’s eyes.

“Herman,” Burly said in a soft, soothing voice, “please don’t cry.”

Herman looked around. He didn’t know where the voice came from. Then he looked down to see Burly smiling up at him.

“Burly! You’re alive! You can talk!”

“Not so loud,” Burly shushed him. “Yes, I can talk, but only when it’s just you and me. When Callie and Tad, or anyone else is around I’m just a regular stuffed animal.”

“But why?”

Burly wrinkled his brow. “I don’t know. I don’t know why I can talk. But when your tear hit the top of my head I began to talk. That’s all I know.”

“Oh this is wonderful,” Herman whispered, hugging Burly tightly. “Oh! I didn’t hurt you by squeezing too right, did I?”

“Oh no,” Burly replied. “We burlap bears are pretty tough.”

“And you’ll be my friend!”

“Of course, I’ll be your friend,” Burly said. “I’ve been your friend ever since I was that feed bag. Remember, you rode in the pick-up to buy me at the feed store.”

“Not really,” Herman had to admit.

“You impressed me because you were so nice and kind and polite,” Burly explained. “And honest.”

“Thank you.”

“See how polite you are. Do you want to know a secret? I t was really my idea for me to be made into a bear. I made the bag rustle underneath your father’s hand that day so he would notice me and get the idea.”

“I didn’t think papa liked me enough to think of it on his own,” Herman sighed, a bit sad.

“Oh no, Herman,” Burly corrected him firmly. “Your father loves you very much. I could have sat there rustling all day long, but if he hadn’t really wanted you to have a bear, my rustling wouldn’t have meant much.”

“Oh.” Herman was happier knowing his father did love him after all.

“And do you know why he left so quickly after the birthday party?”

“He had to check the horses and cows,” Herman replied innocently.

“Wrong again,” Burly said. “He left because he didn’t want you to see him crying.”

“You mean papa cries? Gosh, I didn’t think anybody that big and strong ever cried.”

“Your father cries all the time, but you and your brother and sister don’t know it. He loves you all very much, and it makes him sad when he can’t give you things.”

“I guess things don’t matter as long as I know papa loves me.”

“Oh my, nice and kind and polite and smart too,” Burly sang. “I knew I was right to want to belong to you.”

Herman smiled a little, then thought of Tad and sighed. “I just wish Tad didn’t hate me.”

“Your brother doesn’t hate you,” Burly said. “He’s just jealous because he never got a stuffed bear. And he’s jealous because he has to go to school and help on the farm more than you do.”

“I do what I can,” Herman protested. “I’m only five.”

“Six. But you see, Tad is still just a little boy, even though he is bigger than you, so he doesn’t understand these things.”

“So maybe when he’s older he won’t hate me,” Herman said hopefully.

“Of course,” Burly assured him. “After all, he is your brother.”

Herman smiled and hugged Burly, knowing he would never feel sad or lonely again. “And you are my friend.”

“Yes, and you are my friend.”

Herman heard Callie and Tad come into the house, muttering and crying. He felt sorry they had gotten into trouble but felt good that they would know better as they got older. Like he would know better as he got older, with the help of Burly Bear, of course. He hugged Burly once more.

“Happy birthday, Burly.”

What Maude Learned Too Late

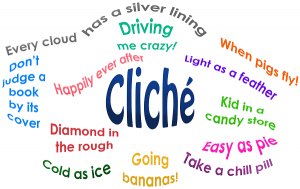

My mother-in-law Maude was always certain she was right because of this list of wise sayings from her mother.

“You get more with honey than vinegar…what goes around comes around…”

No need to list any more of them. They’re all from Benjamin Franklin, Confucius or some other source forgotten in time. Any problem in life could be solved by one of them, and Maude was the first one to remind you of it.

Often I asked her why she thought I was wrong about everything.

“It’s not that I think you’re wrong. It’s just that I know that I am right.”

The rare instance when I was able to prove she was factually wrong and I was right and I asked why she corrected me anyway, she’d reply, “Well, I thought if I didn’t know you wouldn’t either.”

Of course, a sense of being right all the time can create an air of confidence and as we all know nothing succeeds in life more than having confidence. Her biggest success was as a bookkeeper because one and one are always two. She kept the books for the family coal company, and they always had the exact amount of money that Maude said they had. And I say this without sarcasm. Not knowing exactly how much money a business had caused a lot of bankruptcies and kept governments teetering on the brink of insolvency.

For myself, I know intellectually one and one equals two but putting it down on paper has always been the problem. It’s hard to concentrate on one and one when a pretty butterfly flutters by or I consider what happens when the wrong one tries to join to another wrong one. And what was I talking about in the first place?

Eventually Maude’s county elected her to be treasurer. This was in the 1980s when bank interest rates were double digits. She kept the county’s money in various short-term accounts with different banks, and every morning she called each bank to see what the going rates were. Then she transferred accounts to the best rate. She made her county several million dollars just by switching money around. The national association of county treasurers named her treasurer of the year. Not just of small population counties but of every county in the United States of America.

I could not, would not deny Maude this distinction and the achievement of making so much money without raising taxes, fees or penalties. I wish every politician could do that. And I’m sure Maude gave credit to one of her mother’s time-worn proverbs.

What I had trouble with was her translating her accomplishments into moral imperatives to impose her superior judgement onto how my wife Janet and I raised our children, ran our household and chopped onions. My wife Janet was smarter than I was. She was able to hide the pea of our lives as she shuffled the walnut shells right in front of her mother. I, on the other hand, was a terrible bamboozler. Everything I did was out for the entire world to see and criticize.

Maude lived a long and fruitful life. Wisely, her husband Jim became a federal coal mine inspector in his later years thereby insuring his wife had the best health insurance available as she endured several heart attacks. One cannot outsmart death forever, and eventually Maude entered Hospice and awaited the end from advancing coronary disease.

Despite how aggravated I was with how she treated my family and me, I openly admitted that this was the woman who gave birth to the woman who saved my life and gave me two wonderful children. Through the years I took her to her doctor appointments and was by her side as she went from being bed-ridden at home to many hospitalizations and finally to Hospice.

I sat next to her one day when she announced, “I’ve been going through all my mother’s sayings in my mind, and I can‘t think of one that applies right now. For the first time in my life, I don’t know what to do.”

The next day when I visited, her speech was slurred and she had trouble holding up her hands. She had a letter from back home and I read it to her. I asked if she remembered the person who wrote the letter. She feebly nodded her head.

The day after that I found her asleep, a rasping sound escaping her lips. After sitting next to her in silence, I looked out the window and commented that it was raining. When I turned back I noticed she had stopped breathing.

Despite what she said, I think Maude did know what to do. She just didn’t want to do it.

When Maude Became Maude

When I think of my wife Janet’s mother Maude, I can’t help but recall a line from Gone With the Wind. Rhett Butler said of his daughter Bonnie Blue, “She is what Scarlett would have been if it had not been for the war.”

If Maude had not been forced to live through the Great Depression of the 1930s, perhaps her better qualities would have shone through more.

Maude’s father was the chief electrician for a coal mining company in southwestern Virginia which meant the family had a good company house and the older children were able to go to college. As the middle child, Maude became caregiver to her three younger brothers and sister. Her mother also gave her the responsibility of walking to the coal mine every day when the whistle blew to accompany her father home to make sure he didn’t stop in the bar along the way. A small girl didn’t have the actual ability to keep Daddy from going through those swinging doors and stagger back out an hour later. When he finally arrived home, her mother blamed Maude and not her father.

What a terrible moral burden to place on a child, predestining her to fail. Maude spent the rest of her life trying to keep everyone else away from moral turpitude; and, dammit, she was determined not to let her mother down.

When she was fourteen, her father died of tuberculosis, and the coal company kicked the family out of their house because no one there worked for them anymore. Whatever community standing that came with her father’s being the company electrician went away. The money went away. She remembered searching through all the furniture for a missing penny so her mother could mail a letter. The older children helped out the best they could, and Maude and the oldest of her younger brothers went to work. And they couldn’t expect help from the family to go to college either.

One of the bright moments of Maude’s youth was to take the train to the next town over to spend the weekend with her Aunt Missouri. Missouri’s children had all moved away, so she could devote every moment of her gentle attention on Maude. She counted down the days to Friday and the trip. On Thursday evening before she left, a neighbor lady came to visit her mother, bringing along her large, shedding dog. Her mother told Maude to take care of the dog while the neighbor shared the latest town gossip. By the time the woman finished and took her dog home, Maude’s sinuses began to swell from all the dog dander. The trip to Aunt Missouri’s house had to be canceled.

So when Janet and I began having pet dogs, Maude came up with plenty of excuses why we should get rid of them.

“If you didn’t have to spend all that money on the dogs then you could afford to get the children something they really want,” she told me once.

“But what they really want are their dogs.”

Maude arched her eyebrow, sighed in exasperation and muttered, “I suppose you’re right.”

Right before she died, Maude told the story of the canceled train trip to visit Aunt Missouri and how it was canceled because of dog dander.

Another time Maude told us how she was so tired of cleaning house she decided to lie on her bed and pretend she was in her coffin. Everyone in town came by to say how pretty she looked dead and told her mother how they were all going to miss her. Her mother ruined her day dream when she walked by the bedroom.

“You know you’re really not dead and just lying there is not going to get your chores done.”

With great effort and with a sense of martyrdom, young Maude arose from the dead to complete her obligations to the family, which, she was sure, her brothers and sister did not appreciate.

Maude never could sit down of an evening to watch television with the rest of us. She had to wash clothes, iron or fold and put them away. Something in the kitchen wasn’t clean enough. I think she was afraid her mother was going to come back from the grave to tell her to stop watching that silly television and get her chores done.

Of course, all this is speculation on my part. I must remember I wasn’t there, and all I had to go on was Maude’s version of these stories. Who knows what actually happened back then. All I knew was the Maude who survived the Great Depression.

Grandpa’s Secret

Grandpa and Santa

Grandpa had a secret.

Little Jimmy learned what it was on late Christmas Eve as he sat with grandpa watching the tree lights twinkling.

“I can’t wait for Santa to arrive.”

“Me too,” Jimmy said. Then he looked at grandpa. “Why are you waiting for Santa?”

Grandpa gave him a big hug. “I’m going to tell you a secret. Do you promise to keep it?”

“Of course, Grandpa. We’re best friends.”

“Well,” he whispered, “I’ve seen Santa Claus every Christmas Eve for the last 80 years. I caught him leaving presents under the tree, and he said if I promised not to tell anyone he would grant me special wishes. For years I wished for toys. Then I wished to get into a good college. Then I wished I would make enough money to give my children everything they ever wanted.” He paused to wink at Jimmy. “Sometimes you wish you didn’t get everything you want.”

“What do you mean, Grandpa?”

“Well, I don’t know if you’ve ever noticed, but your daddy and your two aunts are awfully spoiled.”

Jimmy smiled. “Yeah, but I didn’t want to say anything.”

Suddenly there was a blast of cold wind and a soft “ho, ho, ho.”

“Well, James I see you have your grandson with you,” Santa said.

“Promise, Santa, I won’t tell,” Jimmy said.

“So, James, what’s your wish this year?”

”I don’t have a wish, except that Jimmy start having his wishes now.”

“He’s a good boy,” Santa said. “I think he can handle it. So, Jimmy, what do you wish for?”

“I just want grandpa to be happy.”

“Done.”

The next morning everyone gathered around the Christmas tree–grandpa, Jimmy, his parents and his two aunts. Jimmy opened each present and hugged and kissed his parents and aunts.

“Dad,” Jimmy’s father said, “you didn’t give Jimmy anything.”

“Yes he did,” Jimmy said spontaneously. “He introduced me to Santa Claus.”

“Introduce you to Santa Claus?” one of his aunts said with shrieking laughter.

Jimmy looked at his grandpa with terror. He had let the secret out. Grandpa nodded, smiled and told his family that he had visited with Santa for the past 80 years. Jimmy’s father scolded him for telling such silly tales to confuse the boy. The two aunts, almost simultaneously, accused grandpa of dementia, to which Jimmy’s father announced that if that were the case then grandpa had to be committed and all his funds taken into a guardianship handled by his three children.

“Oh, yes,” the other aunt added with an evil giggle, “I could take care of Daddy’s money very well.”

Tears filled Jimmy’s eyes as he sat in the judge’s chambers a month later with grandpa, his parents and two aunts. The judge sat at his desk and peered over his glasses at the stack of paperwork in front of him.

“I’m so sorry, Grandpa,” he whispered.

Just then there was a cold blast of air entered the chamber as Santa Claus appeared to Jimmy and grandpa. Everyone else was frozen.

“I wished for grandpa to be happy,” Jimmy said with a pout.

“But you were the one who told,” Santa reminded him.

“Is it too late for me to have a wish?” grandpa asked.

“No, I guess not,” Santa replied.

“I just wish this hadn’t happened.”

“Done.”

With another blast of air, Santa was gone, and the judge looked up from his papers.

“I’m sorry. What were we saying?”

“I was saying,” Jimmy’s father said, “my sisters and I have discussed it, and we think our father has given us more than we deserved throughout our lifetimes. We want our father’s will be changed so that everything will be left to his only grandchild, Jimmy.”

“Oh, I think that can be arranged,” the judge said.

“But Grandpa,” Jimmy said.

“Shh.” Grandpa put his finger to his lips. “It’s a secret.”

A Civil War Christmas

Mary Louise and Santy

Mary Louise could hardly contain herself as she sat by candlelight, sitting as still as a child on Christmas Eve could sit while her mother brushed out her hair. It was the middle of the Civil War and their plantation home in South Carolina was in ruins, but Mary Louise just knew Santa Claus would answer the letter she wrote.

“Now, don’t you go wishin’ for the moon, young lady,” her mother lectured her as she began to tie pink ribbons in Mary Louise’s brown hair, making two, perfectly divided pigtails.

“But if Santy got my letter….”

“I didn’t send Santy’s letter,” her mother said abruptly. “He couldn’t run the blockade anyway if I had sent the letter.” She finished tying the second ribbon. “Blame the Yankees if you don’t get no Christmas this year. It’s their fault.”

Mary Louise knew not to argue with her mother when she got into one of those moods, and she seemed to be in one of those moods all the time recently. After her mother left the bedroom, she scrambled to her desk and pulled out a piece of paper and a pencil and proceeded to write the very same letter over to Santa Claus. She had but one wish.

“Please, Santy, let me see my daddy one more time.”

Folding the letter neatly, Mary Louise went to the window, opened it and tossed it out in the cold night air. Her mother always told her Santa Claus was magical so she knew her letter would reach him on the winter wind of Christmas Eve. Content she had done all she could do to ensure a merry Christmas, Mary Louise closed the window and ran to her bed where she buried deep underneath the many layers of down-filled quilts. No time had passed since she closed her eyes, it seemed, when she felt a cold blast, a gentle ho ho ho and the familiar baritone chuckle of her father.

“Daddy! Santy!” Mary Louise whispered excitedly.

Jumping from bed she ran to give her father a big hug. She knew it had to be her father because no one could hug as well as he did. She sniffed. Yes, it was the smell of his sweat and a slight hint of his favorite Cuban tobacco. But Mary Louise detected another scent, unfamiliar, acrid, almost taking her breath away.

“I can’t stay long, darlin’,” her father said. He pulled her away. “Let me look at you. You’ve grown an inch since I last seen you. And still got that purty smile.” He hugged her again. “Always keep that purty smile, darlin’.”

“Oh, Daddy, I just have to give you a Christmas present!” She turned to Santa Claus. “Isn’t that right, Santy?”

“Yes, Mary Louise, that’s right,” Santa replied.

“And I know just what to give!” Mary Louise stuck out her hand. “Give me your tobacco pouch, Daddy.”

Her father pulled a leather pouch from his tattered, soiled gray trousers and handed it to her. Mary Louise ran downstairs to the parlor and opened a drawer in a large old desk. She gently lifted the lid off a humidor and carefully scooped out the last of the fragrant Cuban tobacco into her father’s pouch. She quickly returned and proudly presented it to him.

“It’s the last, Daddy. I knew you would want it.”

“That’s mighty kind of you darlin’. I’ll never forget it.”

“It’s time to leave,” Santa said.

“But I have to give my little darlin’ something.”

“Oh, Daddy,” Mary Louise said in a soft voice, “just you being here is all the Christmas I need.”

She watched her father’s eyes fill with tears as he pushed his long dark hair from his forehead. Her nose crinkled as she noticed his hair had begun to turn just a touch of gray. Mary Louise’s head cocked when he pulled his pocket knife out and opened it.

“I know. This will be from me to you for all the Christmases in your rest of your life.”

The next morning Mary Louise jumped from her bed and flew down the stairs to the kitchen. She felt one side of her neatly parted hair fly free of the pink ribbon, but she did not care. She had to share with her mother the happiness of her visit with her father, all thanks to Santa Claus.

“Oh Mommy, Mommy! It was wonderful last night! He came! He came! Santy came and he brought Daddy with him!”

Her mother looked up from her cup of coffee as she sat at the table. Her hands covered a letter.

“What on earth are you talking about, Mary Louise?”

“After you left me last night, I wrote another letter to Santy and threw it out the window. And he got it. He woke me up with his ho ho ho and when I opened my eyes I saw Daddy!”

“You were dreaming, child.”

“No, I wasn’t dreaming! It was real!”

“That’s foolishness! Now sit down and eat your breakfast.”

“No! I’ll prove it!” Mary Louise ran to the parlor, brought back the humidor to the kitchen table and put it down. “See, all the tobacco is gone.”

“That was the last of your father’s favorite tobacco. Very expensive tobacco from Cuba. What did you do with it?”

“I gave it to Daddy. I put it in his pouch. I wanted him to have it,” Mary Louise said softly.

“You dreadful child! You threw away your father’s tobacco as part of this cruel joke that he was here last night!”

“But it’s not a joke, Mommy. Daddy was really here. Santy brought him.”

“That’s impossible!”

“Why, Mommy?”

She watched her mother sink into the chair, dissolve into tears and hold up the letter on the table.

“Because this letter says the Yankees killed your father at a place in Maryland called Antietam. I got this letter three weeks ago, so there’s no way your father could have been in this house last night! And why would he have come home and not….” Her voice choked. “…and not visited me?”

“Maybe,” Mary Louise whispered, “because you didn’t write a letter to Santy.”

Her mother arose abruptly and shook Mary Louise’s shoulders.

“You terrible child! How can you be so mean to me, especially here at Christmas?” She stopped and reached out to touch the loose strands of hair on the side of Mary Louise’s head. “And you lost one of the ribbons from your hair. Do you know how expensive ribbon is now?”

“I’m sorry, Mommy.”

“I’m so angry I can’t stand the sight of you! Go to your room and stay there all day!” She stepped away, picked up the letter and folded it. “I shall spend the day in prayer, asking God to give me the strength to forgive you. Perhaps all will be better tomorrow.”

Mary Louise turned and without another word went to her room. There she decided she would never write another letter to Santa Claus again. It was not that she no longer believed in Santa; no, it was because she decided there was no use in asking Santa to give her something if no one believed her when it happened. She pulled out a lock of dark hair streaked with gray tied with a pink ribbon. It was her present from her father. Mary Louise was afraid to show it to her mother because she might throw it away, and Mary Louise wanted to keep it forever.

Her mother forgave her the next morning and gave her extra jam to go on her biscuits. Her mother never celebrated Christmas as long as she lived. This is not to say Mary Louise never had a merry Christmas again. She had a life-long love affair with Christmas, starting with her eighteenth year when she relented and wrote another letter to Santa Claus on Christmas Eve, folded it and tossed it out in the winter wind.

“Dear Santy, Since Mommy hates Yankees so much, please bring me a nice Yankee boy to marry.”

On Christmas Day, a school friend, who knew Mary Louise’s mother never celebrated the holiday, invited her over for dinner. In the parlor was a tall, willowy young man with long straight dark hair and soulful eyes.

“Mary Louise, I want you to meet my father’s new assistant, Thomas. He’s from Ohio.”

Mary Louise was impressed with Thomas’s strong but gentle handshake. By that evening they were sitting close to each other by the parlor fireplace. Instinctively she leaned into him and he placed his arm around her shoulder. With her head on his chest she sniffed. His sweat smelled like her father’s. She sniffed again.

“Do you smoke a pipe?”

“Yes,” Thomas said. “It’s my only vice. I buy the tobacco from Cuba.”

Mary Louise and Thomas were married by the next Christmas. On Christmas Eve she pulled out the strand of hair tied with the pink ribbon and told him the story of her Civil War visit from her father. She also told him about her letter asking for a nice Yankee boy. He believed her. They had five boys and three girls, each carefully taught to write letters to Santa Claus, fold them neatly and throw them out the window onto the winter wind of Christmas Eve.

Which Tree?

Three fir trees on the edge of the forest were chatting one morning in early December.

A huge fellow, about twenty feet tall and wide at the base, ruffled his limbs. “I don’t know what you two guys are planning for Christmas but I expect to be center of attention downtown this year. Oh yeah, on the square overseeing the Christmas parade. Anybody who is anybody will be there with their kids watching the parade pass in front of me. I’ll be lit to the max with lights and a star on top.”

“That’s nothing,” a ten footer with lush green boughs replied. “I mean, if you go for that common man scene where they let absolutely everyone near you, I suppose that’s okay. As for myself, I’m selective about my company. Not saying I’m better than anyone else, but let’s just say I have discerning taste. I’m winding up in the grand foyer of a millionaire’s mansion, decorated with only the most expensive ornaments and lights. I’m talking Waterford crystal here, and I’ve got the branches to hold them.”

The third tree, not more than three feet tall and with scrawny limbs, just stood there without much to say.

“What about you, junior? What do you expect to be doing on Christmas morning? Brunching with the chipmunks?” The middle-sized tree blurted forth a forced ha-ha-ha. A nice baritone but shallow as could be.

“Now, now,” the largest tree chided. “We shouldn’t make fun of our inferiors. We all can’t be the best, most important Christmas trees in town. Not even second best, like you who will be charming to a small group but not as the official town tree.”

The littlest tree felt like he was about to ooze sap out of sadness but knew it wouldn’t do any good. The other trees were right. Who would want him except for kindling for the fire? He wasn’t big enough to make a decent Yule log.

Just at that time a caravan of cars leading a large tractor-trailer truck pulled up in front of the three trees. A group of important-looking dignitaries crawled from their cars and circled the largest tree as the crew pulled its equipment from the truck.

“Oh, yes, I think this one will do fine,” a large bald man announced as though he was thoroughly practiced at making important decisions.

“Oh yes, Mr. Mayor, this one will be more than fine.” The others standing next to him quickly agreed with him.

The crew started its chain saw, chopped the fir down and laid it on the flatbed truck.

“See you never, suckers!” the biggest tree called as the municipal procession disappeared.

“Commoner!” the middle-sized tree replied.

A couple of hours passed before a long limousine with shaded windows rolled up to the two remaining firs. A chauffeur jumped from the driver’s seat and opened the door for a couple elegantly dressed in fur and leather. The woman, with her artificially colored blonde hair piled on her head, sipped from a champagne glass, while the man fixated on his cell phone.

“Oh, Maxim,” the woman cooed. “You did a wonderful job scouting out the most beautiful tree in the forest.” She ran her fingers across the chauffeur’s broad shoulders. “Of course, you do everything well.” She turned to the man on the phone. “So, what do you think Joey? Is it big enough for our grand staircase?”

“Yeah. Sure. Whatever.” The man didn’t look up from his phone. “Max, cut it down.”

The chauffeur cut down the middle-sized tree, carefully tied it to the top of the limousine and they got into the car to drive away.

“Good luck, shrimp! You’ll need it!” the tree called out as the car disappeared around the bend.

At the end of the day, the sky darkened, and a small old car rambled up to the small tree and stopped. Three small children poured out of the back seat and ran to the little tree.

“Oh, daddy, this one will be perfect!” they sang as a chorus.

“That’s good,” a young man in ragged overalls said. “Anything bigger wouldn’t have fit in the car.”

A wispy haired young woman came around the car. “Stand back, children. I don’t want you close when your daddy starts using that axe.”

“Oh, Mommy, you worry too much,” one of the children said with a laugh.

On Christmas Eve, everyone in town gathered on the square to watch the Christmas parade and ooh and ah over the beautiful lit giant tree. Floats rolled by, and the people on them pointed and shouted at the town’s big Christmas tree. Bands with drummers, tubas and more marched past. Each one made the tree feel prouder and prouder.

On Christmas Eve night, elegantly dressed couples gathered in the millionaire’s mansion and oohed and awed over the beautifully decorated tree by the grand staircase. They all drank champagne and nibbled on appetizers served on a silver tray by Maxim who also turned out to be the butler. The ladies in their lovely gowns asked the millionaire’s wife when they were leaving for their estate in the Bahamas.

“Midnight,” she replied. “We always spend Christmas day in the Bahamas. It’s our family tradition.”

Also on Christmas Eve night, across town in a small wooden house, the family decorated the little tree which they placed on a table in the corner of the living room. The room smelled delicious from the freshly popped corn which they strung and hung on the tree. The children kept busy coloring, cutting and hanging the new ornaments on the little tree. The room was alive with the constant giggling of the children, and the little tree decided this wasn’t a bad place to be.

The next morning, everyone in town was home, opening presents and enjoying Christmas dinner with family and friends. The large tree downtown had already been forgotten. It kept hoping to hear another oom pa pa coming down the street but it didn’t. The enormous fir shivered first from the cold wind and then from the loneliness. It couldn’t decide which was worse.

In the millionaire’s mansion, everything was dark and still. All the elegantly dressed people were gone. Numbing silence replaced the insincere wishes for a happy holiday season. The middle-sized tree decided all that Waterford crystal was making its branches droop. Not even Maxim was there.

Meanwhile, in the small house across town, the family gathered around the tree to open presents. The children tore away wrapping paper to see new socks and underwear and hugged their parents gratefully for it. Then they cooked their modest Christmas feast and settled back around the tree with their plates in their laps and ate every bite of it.

Now you tell me. Which was the grandest Christmas tree of all?